In a blow to hopes for finding water and life on Mars, scientists think bright streaks detected inside Martian gullies after 1999 were not spurts of water, but rather avalanches of dust.

Water is thought to have covered much of Mars in the past, but whether or not the life-giving substance has shown up in the recent past is a matter of debate among scientists.

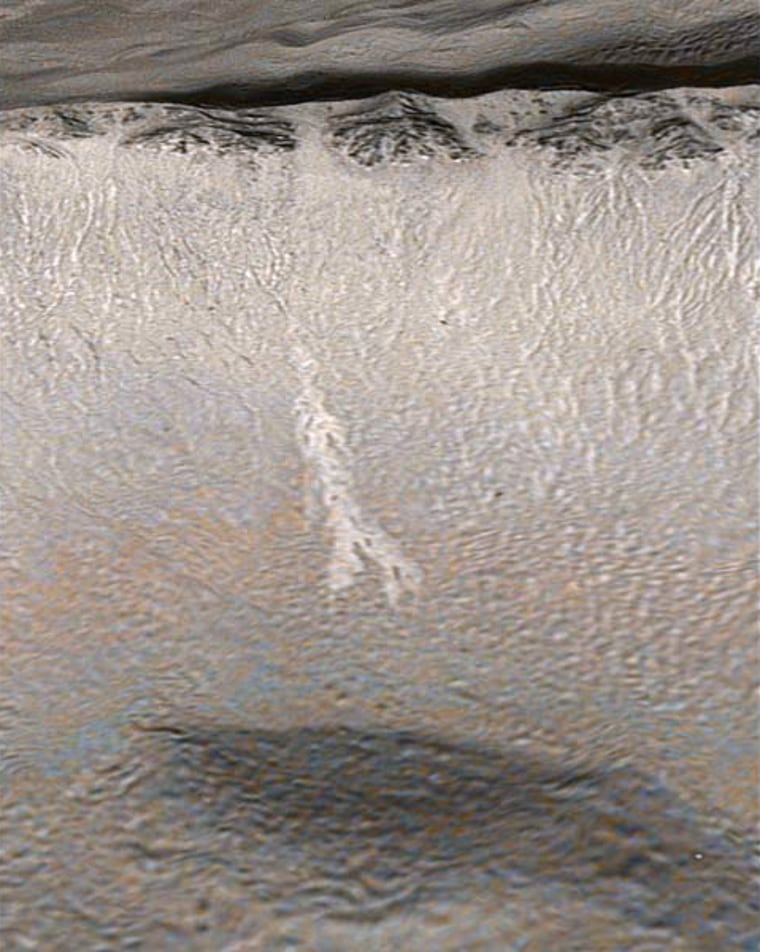

The strange, streaky formations were not present in Mars Global Surveyor 1999 images of the gullies. Seven years later, however, the bright streaks made their debut in new images, prompting Michael Malin of Malin Space Science Systems and his colleagues to conclude that a recent burst of Martian groundwater might be responsible.

But Jon Pelletier, a geoscientist at the University of Arizona (UA) in Tucson, and his team now say "pure liquid water" is unlikely to have made such formations in the Centauri Montes region of Mars.

"The dry granular case was the winner," Pelletier said, referring to a dusty mode of creation. "I was surprised. I started off thinking we were going to prove it's liquid water."

Pelletier and his colleagues' findings, which are based on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter images taken by High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera, will be detailed in the March issue of the journal Geology.

Since 2006, HiRISE has provided the most detailed images of Mars ever taken from orbit, giving Pelletier a chance to offer a second opinion on the existence of liquid water that might still support life beneath the Red Planet's surface.

"What we'd hoped to do was rule out the dry flow model," said Alfred McEwen, a UA professor and leader of the HiRISE team. "But that didn't happen."

Although the new study doesn't rule out a watery creation of the bright streaks, Pelletier and McEwen said a bone-dry avalanche of dust and rocks is the most likely culprit.

Their conclusions stem from work with 3-D maps created with HiRISE image data.

"This is the first time that anyone has applied numerical computer models to the bright deposits in gullies on Mars," Pelletier said.

When he compared the bright deposit and its HiRISE image to the predictions made by the model, the dry avalanche model was a better fit.

"There are other ways of getting deposits that look just like this one that do not require water," Pelletier said.