Who lost it on Lost Temper Creek? What horror befell the village of Eek? Does it have anything to do with another town being Chicken?

Native traditions and colorful settlers have given Alaska an extra helping of oddly named places. Try Nunathloogagamiutbingoi Dunes or Dakeekathlrimjingia Point, unpronounceable and unexplained other than being of Eskimo origin. Then there's Sagavanirktok, a North Slope river named after an Eskimo word for strong current.

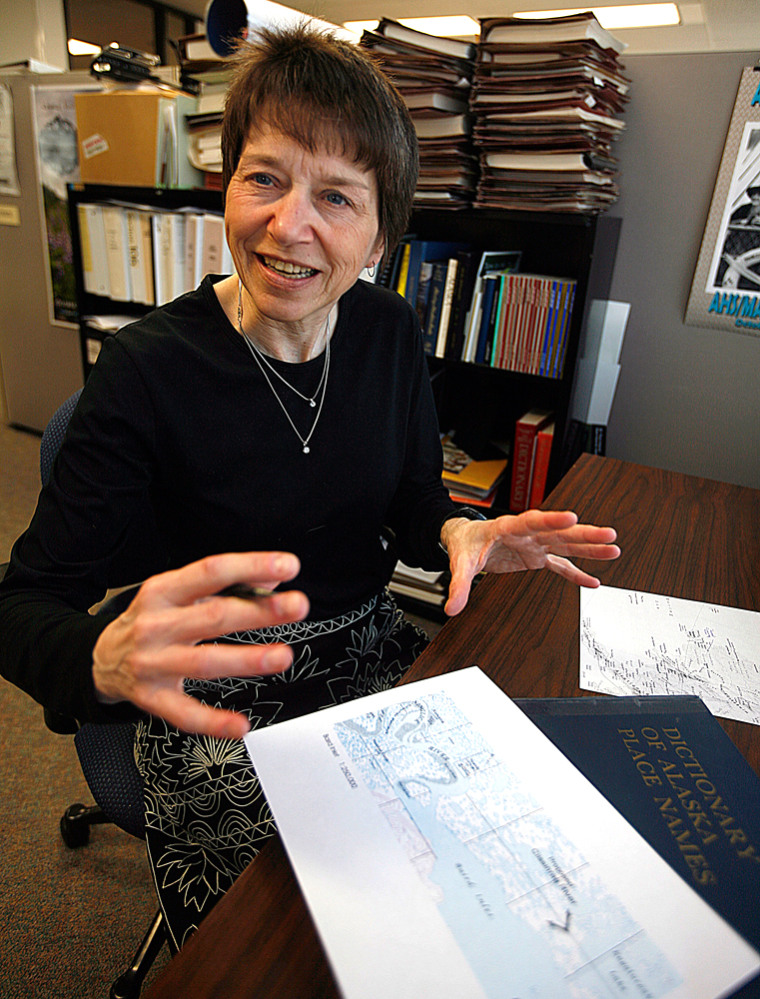

"It just rolls off your tongue — at least my tongue," said Donald Orth, a retired geographer and cartographer with the U.S. Geological Survey. He wrote the book on Alaska place names more than four decades ago, and now that book is getting freshened up.

"Dictionary of Alaska Place Names," published by the USGS in 1967 and reprinted with minor revisions in 1971, is an enormous guide though the mundane and the quirky.

An Anchorage-based publisher plans to create an updated version of Orth's long-out-of-print book. Flip Todd, owner of Todd Communications, hopes to have it out by 2009.

Supplements to Orth's thousand-plus-page monograph were published until 1994, listing additional place names recognized by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

Discovering the stories behind the names

All place names in the U.S. can be viewed online on the board's Web site, but there's no way to peruse the entire text for the simple pleasure of discovering the stories behind odd or whimsical names.

That's a deficiency that needs fixing as far as Todd is concerned.

"There are still too many advantages in this low-tech device called a book," he said.

In the original, Orth included variant names and sometimes humorous stories behind many geographic monikers.

Mishap Creek, aka Big Loss Creek, is Unimak Island stream named for a lighthouse keeper who stripped naked to cross the water, then tried to throw his clothes to the other side, only to watch helplessly as they landed downstream and disappeared.

There's Chicken, an old mining town established during the Klondike Gold Rush. A detailed history of the name is not in Orth's dictionary, but according to oft-told lore, miners wanted to call the community Ptarmigan after a bird common to the area, but no one knew how to spell it. So they settled on Chicken, since miners also called ptarmigans "tundra chickens."

Atlasta Creek was inspired by a remark uttered by the wife of the owner of a nearby roadhouse after the first building was completed: "At last a house."

How Lost Temper Creek got its name

Lost Temper Creek, an Arctic Slope stream, was named over a "camp incident." Eek, a western Alaska village, was derived from an Eskimo word that means "two eyes." Big Bones Ridge, in the Talkeetna Mountains, came from the large fossil mammoth or mastodon bones found at the site.

Orth's book came about as a centennial commemoration of the 1867 purchase of Alaska from Russia. He led a team of researchers, but he had already begun collecting place names as a hobby during his time surveying Alaska's Brooks Range for the USGS in the 1950s.

Alaska is the focus of Orth's most extensive place-name work, but he has worked on projects covering all 50 states during his long career. The subject holds no end of fascination for the former executive secretary of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.

"Language, history, geography, all of those things come together," he said during a phone interview from his Falls Church, Va., home. "Place names are part of the language, part of our psyche."

What stands out about Alaska for him are the numerous native names given by the state's indigenous people, besides other influences from explorers and settlers.

Also, Alaska is so vast and wild that a multitude of mountains, lakes, streams and other geographic features have no names, and might never get them.

That's as it should be, said state historian Jo Antonson, who works with the state board that considers new place-name proposals.

"There really has to be a good reason to name something in a designated wilderness area," she said. "The philosophical concept is that wilderness is untouched, unaffected by the technology of man."