Condé Nast Traveler stuntman Mark Schatzker is on a mad quest to make himself into a

The funny thing about Renaissance Men is that there is no recognized international standards body. A Renaissance Man doesn't have to pass any kind of exam or pay for some kind of license, and he doesn't have a plaque hanging on his wall the words "I hereby certify that ..." followed by his name in laser-printed calligraphy. Any mono-talented fool can rent a storefront in some suburban strip mall and go into business as a Renaissance Man. It's just not right.

So let me be the first to lay down the preconditions for what it takes to be a Renaissance Man: You have to work in at least two different fields for a member of authentic European nobility.

Well, you'll never guess what I did last night. I spent the evening at the home of a real-life Italian count. I cooked him and his guests dinner — okay, I cooked the first course. And then we spent somewhere in the region of 38 seconds admiring my painting. I am now a Renaissance Man. It doesn't feel all that different, to be honest, except for this euphoric tingling sensation all over my body, like the archangel Gabriel is sprinkling ferry dust on me. It's pretty cool, actually.

The night got off to a hectic start. We arrived at the villa, and I made straight for the kitchen to get my dish underway. Back in Paris, Christophe Raoux — who's presently doing a stint at Benoit New York, so for anyone who lives in the Big Apple, now would be a very good time to visit — taught me how to make a filet of turbot in a matelote sauce. I had to augment the recipe for Lake Como — replace the turbot with lavarello, which is the lake whitefish that's presently in season. And I had to make the matelote sauce with a bunch of large, yellowy fish heads from some other species that came out of Lake Como. I decided to serve the fish with a thin line of puréed potatos, and on top just a sprinkling of diced missoltino.

In theory, it was an inspired dish. In practice, there were problems. The first was that I had less time than I thought. The matelote sauce needed at least another 45 minutes to reduce into the kind of flavorful nectar beloved by the French. I had more like 15 minutes. It tasted fine, but it was too watery, which made plating something of a challenge.

There was also a problem with the stove. It has been my observation in life that the rich invariably have extremely expensive and highly dysfunctional stoves. The count is a case in point. One of the burners wasn't working, and the knobs that adjust the flow of gas were so hot that using them was physically hazardous.

But enough excuses. As the chef, I accept responsibility. I should have taken more time. I should have been cooking ahead of the meal, so to speak, not behind it. Still, it was not a disaster. I think the presentation would have disappointed Christophe, and I pray that Monsieurre Ducasse never lays eyes on the photo. It tasted pretty good, though.

Following dinner, we repaired to the sitting room. The count admired my painting for a moment, and said this: "It's good for a beginner. To be a great painter, you need to have the gift." The man has a point. He then gestured to a wall on which hung many other paintings and said, "It reminds me of these." I waited, anticipating that he would point at each work of art and rhyme off some big names in European painting. He said, "They are by my mother."

We sat. We drank. I was hoping to play the count my music, but he began recounting a series of tales all beginning with, "Many, many years ago?" A good Renaissance Man knows not to get into stereo wars with his patron.

And that was it. From thence forward, it was all the count. As one story turned into a another, I realized why there are no Renaissance Men anymore. Ultimately, they're just hired help. Leonardo Da Vinci may have painted the Mona Lisa, invented the helicopter, and the nude man inside the circle. But back in the day, he was just the Medici's guy in Florence. Those, as they say, were different times. If he were alive today, he'd have something like fourteen start-ups under his belt. His cup would be runnething over with venture capital.

Who knows? Leonardo might even have his own villa on Lake Como. That's what I'm aiming for. They start at around $5 million. That's a lot of money, but when you factor in all the Schubert CDs I plan on selling, not to mention a side gig as a gardening consultant, a stint on the PGA tour, and my forthcoming chain of Renaissance-style restaurants, then it won't be long before I get in a bidding war with some Russian billionaire. And if I get my mother to whip up some paintings for me — I can teach her how it's done, don't forget — then I'll save a bundle on art.

See you then.

Thank yous

A trip like this could not and would not happen without the help of many others. Thank you, Klara Glowczewska, for editing such a fine magazine and underwriting this educational and transformative experience. Thank you, Ted Moncreiff, for keeping me on point. Always. Thanks, Hyla Bauer, for making me look good. Thanks Lily Newhouse for the invaluable logistical assistance. And thanks Tom Loftus for editing this blog and correcting all my Renaissance (mis)spellings.

Thank you Greta for letting Daddy go away to "visit the horsies" for an entire month.

And finally, my wife. Behind every good Renaissance Man is a forlorn pregnant woman who's had just about enough of doing dinner and bath every evening for a month. Laura, only one more night before I'm back home in your sweet embrace. Please keep in mind that I've been cavorting around Europe in 5-star luxury. Fluff the pillows accordingly.

You see before you "La Villa Clooney." I for one and shocked. I'm not saying this painting is going to be hanging in the Louvre anytme soon — the Musée d'Orsay would be more appropriate — but those of you with some familiarity of my artistic history will be able to appreciate this feat of applying paint to canvas.

Let's give credit where credit is due. If Giuliana Gandola hadn't been standing behind me and guiding me, saying things like, "Don't be afraid. Just use the brush," or "No, not like that," and if she hadn't helped me with the Herculean task of mixing colors, then the result would have looked considerably different. At one point in the process, George Clooney's villa was looking more like George Clooney's dilapidated shed with a crooked roof. The problem was one of perspective, and Giuliana helped me fix that.

But most of the paint on that canvas was put there by me.

Of course, it's not enough to just look at a painting. You have to "understand" its deeper meanings. So for those of you not schooled in the intellectually thrilling arena of art criticism, you may be missing out on some high-quality nuance. This is a work rich in meaning. Allow me to explain.

George Clooney's villa is symbolic of not only of George Clooney's villa, but of nice villas everywhere. In this way, it is a universal symbol.

The mountains are symbolic of extremely tall hills made out of rock that are not only majestic and grandly imposing, but also they're difficult to get over. They represent the boundary separating George Clooney's special world from our own.

The man fishing in the boat. This is George Clooney, and by the looks of things, he's hauling in a sizeable lavarello. This is the painting's most significant feature. Clooney as fisherman is symbolic of: a) Slow Food; b) Jesus; c) A sly nod to Clooney's appearance as Lenny Colwell on an episode of "Riptide" in 1984. ("Riptide" was an awesome show. Almost as good as "Simon and Simon.")

The man rowing the boat. This is the "artist" (me). Artists first started putting themselves in pictures during the Renaissance. For example, in Boticelli's "Adoration of the Magi," which hangs in Florence's Uffizi Gallery, you can see Boticelli staring back out at the viewer. It's like Boticelli is saying, "Hey, how's it going?" That's what I'm saying, too.

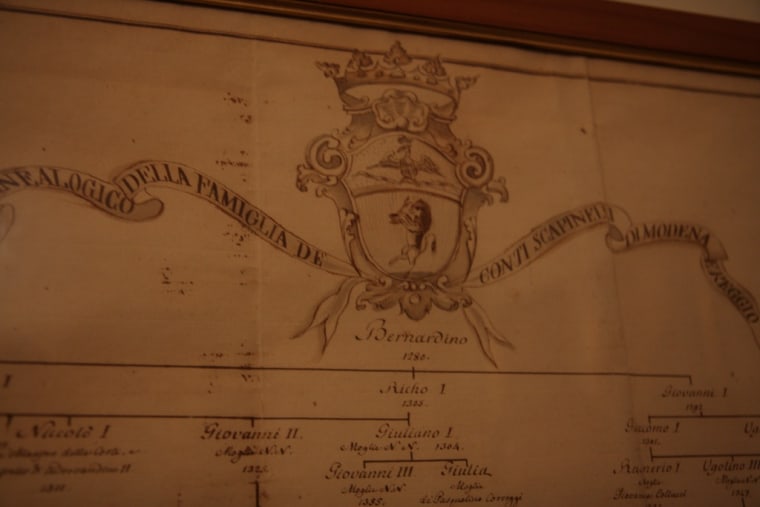

Tonight, I will be presenting this painting to Count Gherardo Scapinelli. The Count lives in one of the grandest villas in all of Lake Como; it was designed by the same architect who did Milan's La Scala opera house. His family tree goes back to the 1280s. His aunt was Ernest Hemingway's lover, and Hemingway — who, I would like to point out, was an incredible writer but didn't exactly leave a lasting impression with his cooking or piano playing — wrote his one and only children's story for the Count.

I will also be cooking for the Count. And while we eat and appraise my work of art, we will listen to the to produce.

And who knows, I might even write and dedicate a children's story to the man. It will be about golfing and , though I might throw in a talking animal to give it some zip.

This, in short, is the big test. In a few hours' time, I will see if I have what it takes to be a real Renaissance Man. Wish me luck.