Liquor connoisseurs may clamor for rare, decades-old scotches, but these superlative spirits are as common as Absolut — at least when compared to the boutique creations from Gardiner, New York’s tiny Tuthilltown Spirits.

This artisanal distillery handcrafts small-batch liquid luxury, such as vanilla-nuanced Hudson River Rum and local-corn-fueled Hudson Baby Bourbon, which is New York’s first production whiskey since Prohibition. Bourbon gourmands can either buy limited-release bottles — or snag an entire wooden barrel of bourbon that Tuthilltown will age until the liquor, and you, are ready.

“For $1,200, you’ll get three gallons of 92-proof bourbon,” says Tuthilltown’s co-owner Ralph Erenzo. “When you want it” — five, 10, 20 years later — “we’ll inscribe your initials on each of your 30 bottles,” he says.

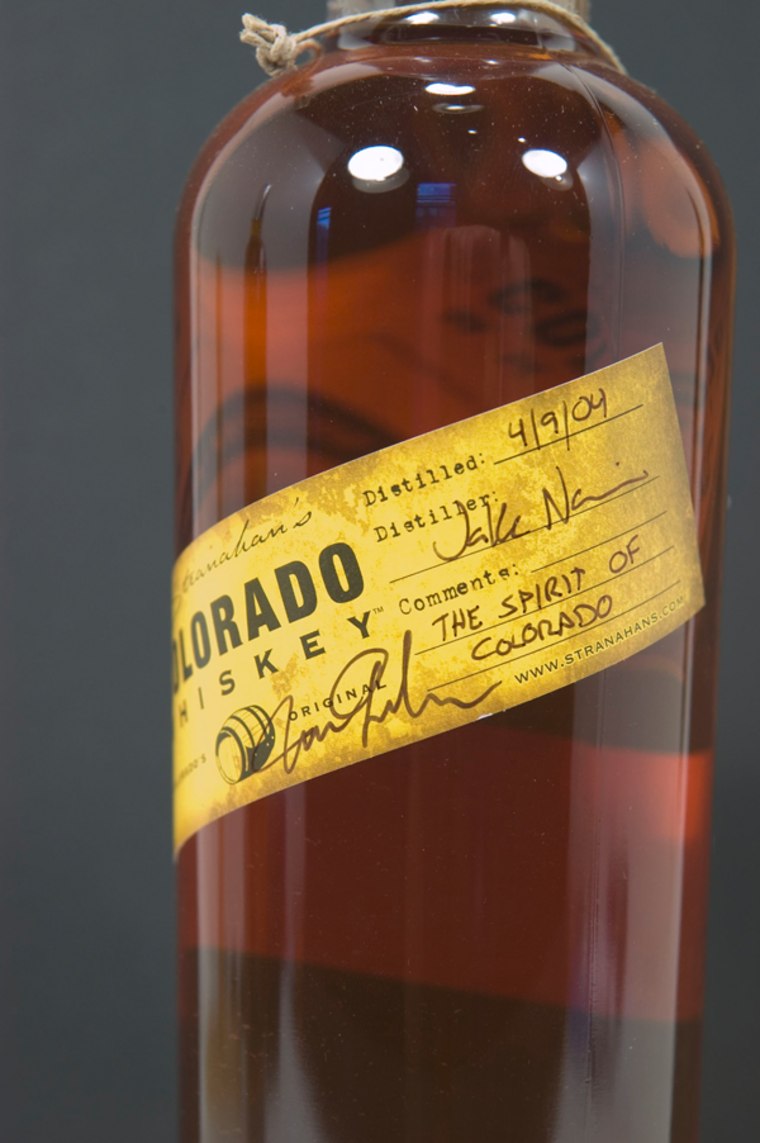

Such hands-on commitment symbolizes America’s burgeoning microdistilling movement, which is slowly breaking Jack Daniels’ stranglehold. Twenty years ago in the U.S. and Canada, there were about a half-dozen independent microdistilleries; nowadays, there are nearly 100, from Philadelphia’s Bluecoat Gin to Iowa’s Templeton rye to Denver’s Stranahan’s, which makes whiskey with filtered Rocky Mountain snow.

“The number of licenses for producing distilled spirits is increasing every year,” says Frank Coleman, senior vice president of the Distilled Spirits Council. He says the increase is attributed to changing legislation. “Prohibition-era blue laws don’t make sense in a modern economy. On the 75th anniversary of Prohibition’s repeal, many states are changing laws to allow people to distill spirits.”

Barriers to success

They’re not changing fast enough for some distillers.

“The government creates lots of barriers to success. There’s no blueprint to starting a distillery,” says Rich Stabile, owner of just-launched Long Island Spirits. Stabile’s company makes high-end LiV vodka, Long Island’s first licensed liquor since the 19th century. Stabile and Co. spent more than 18 months restoring a barn (located on an 80-acre potato farm) and navigating Byzantine layers of government, before starting production in late-winter 2008.

“That was 18 long months without a paycheck,” he says, “but now we’re overseeing everything from the fermentation to bottling, while using some of the world’s finest potatoes: We’re allowing the Long Island potato to thrive outside of North Fork potato chip companies.”

Instead of taters, Steve McCarthy’s muse is far sweeter. “I’m committed to crafting high-quality spirits out of Oregon fruit,” says McCarthy, whose Portland, Ore., Clear Creek Distillery specializes in eau de vie, which are clear brandies made from fruits like cherries, apples and pears. “The fun is finding fruit that helps convey a sense of place. Right now, I’m looking out of my office, and we’re crushing blue plums.”

McCarthy was an early champion of America’s microdistilling movement. He launched his company more than 23 years ago, “and we went absolutely nowhere for probably 15 of the 23 years we’ve been in business,” he says. Despite the rollercoaster economic ride, McCarthy’s remained steadfastly dedicated to stretching people’s perception of spirits. He’s created oddities such as Douglas fir-flavored liquor, grown apples inside of bottles then filled with apple brandy, and even fashioned his own eponymous, peaty Scotch whisky. It’s aged in sherry casks and air-dried Oregon oak barrels — and comparable to anything sold in Scotland.

“The last time we made this, we sold out in two days,” he says. “It’s hard to keep up with demand.”

Distilling 101

For other distillers, it’s harder to educate customers. “Some people don’t know how whiskey gets its brown color,” says Tuthilltown’s Erenzo. To combat this lack of knowledge, he often travels to restaurants and liquor stores to give “distilling 101 lectures.” (By the way, freshly distilled whiskey is clear; it slowly takes on the color of the wood in which it’s aged.)

That’s something a big distiller can’t do, says Erenzo. “It makes a big difference to get out there and meet people… This is a grassroots revolution, and I still get up at 6 a.m. every day and turn the furnaces on and keep the mash going.”

This do-it-yourself ethos has long been synonymous with microbrewers, many of whom are making inroads into the spirit field. “The first step in distilling is fermentation. If you have the skills to make beer, then you can start making spirits,” says the Distilled Spirits Council’s Coleman.

In San Francisco, Anchor Steam’s owner, Fritz Maytag, runs Anchor Distilling, where he creates colonial-era single-malt whiskeys of the kind that George Washington might’ve made. In Bend, Ore., the people behind Rogue Ales started Rogue Spirits, and now churn out piney Spruce Gin and rum formulated with Hawaiian cane sugar and champagne yeast, then aged in Jack Daniels bourbon barrels. (And don't miss the Rogue House of Spirits bar.)

Despite this rampant innovation, microdistilling remains in its infancy. These small-potatoes spirits are barely a drop in the $58 billion booze market. Still, McCarthy notes, “look at the evolution of winemaking in America. When I was in high school in the ‘60s, there were only three or four wineries in America. It was all factory-made stuff; wineries completely rewrote the book. Now we’re making up the rules.”

But, he admits, “this is a very long-run proposition. Even after being eyebrow-deep on this business for 23 years, I can’t tell you I know how it’s going to end up.”