Majestic deltas, magnificent beaches, and a festival that makes Mardi Gras look like a convention of accountants—just a few of the attractions luring European surfers and canny capitalist dropouts into the vast reaches of Brazil's sparsely populated northeast coast. Anthony Chase feels the heat.

By chance, I arrived in the harbor city Fortaleza, the capital of Ceará and the gateway to Brazil's northeast coast, toward evening on a Sunday. As the wide sun settled down onto the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of people swarmed along the waterfront—on the streets, in the water, on the sand, across the four-lane highway, which had been closed to traffic for the Festival of Sexual Diversity.

I went out of the hotel, trying to make my way toward the distant source of the music and the pounding drums. The whole city was like a subway car at rush hour. You didn't so much walk as slither among the oiled and barely dressed bodies, the exuberant jostling flesh. I couldn't get too close to the central bandstand, but it didn't matter. As if in some medieval definition of God, the center of the party was everywhere and nowhere. Lured by the prospect of exploring the remote and relatively unpopulated coastline of northeastern Brazil, I had traveled several thousand miles only to find that I had been ingested into the emotional core of amor livre. On and on: the great droning bang and the throbbing of sticks landing on barrels and skins. It sounded African, as if the continents had drifted back together again.

I was experiencing agoraphobia and claustrophobia at the same time. Total strangers smiled and offered me food and drink and said hello. Free love, and free food and free drink, and free tokes of this and that … I gave up trying to maneuver, found an empty beach chair, and sat down. With my head beneath the seething surface of the dancing bodies, I felt relief. Like a barnacle in a coral reef, I let the sound and bodies wash around me.

Gay, straight, bi, drag, semi-drag—arm in arm the exhibitions of possible lifestyle permutation sauntered past. It was a chromosomal swarming. Every skin color. All ages. The whole genetic range. I lost the ability to find labels or categories for what was happening. Who knew? Who cared?

There was full frontal nudity. Or ostrich feathers. Or enough costume material for three operas at the Met. Some paraded. Others simply sat, applauding each new instance of the transcendentally outrageous. It was a musical ayahuasca. There were short sociopolitical harangues between the songs—"Por um mundo sem homofobia," "Não o sexismo," "Não o racismo," "Não o machismo"— which everyone ignored.

Eventually it became clear that the concert was giving way to a parade. Each of a dozen bands rode on a three-story-high platform built atop a tractor-trailer truck, which inched up the coast. The block-long rigs were draped in brilliant cloth, a motorized version of the chargers in the Middle Ages, dangling shields, blankets, trinkets, anything that could capture and intensify light. The side of each semi facing the audience and the sea was an amplified black wall of woofers, tweeters, bass, subwoofers that destabilized any tumors you might be starting to grow. The chair I sat in quivered underneath me. I skittered around on the sidewalk like a piece on a Ouija board.

One by one the sound flotillas drifted east. On each rig were not only musicians but handlers, hookers, lookers, lookers-on. There were whole city blocks of people dancing on the rolling trucks: bodybuilders with built bodies and no clothes but those Speedos; women with spinnaker chests; headdresses; spears—it made Mardi Gras look like a convention of accountants. I heard the reincarnation of John Bonham, who turned out to be an unassuming white guy in shorts, a T-shirt, and a baseball cap. His lower body churned out a stately backbeat, while his twelve-armed upper body whirled 359 degrees, letting fly. Somehow what he generated reached inside your rib cage. It was a mind infarction, like applying chest paddles to the groin.

This heartbeat throbbing was the world; it was real culture, a sound that amplifies, fuses people with one another, reassures. As this drummer set the songs going, women leapt to their feet and gyrated in the balmy night. They would dance with anyone, even a cadaverous loser like me. They grabbed me. They implored. When I replied in flawless Portuguese that I was there for ethnographic purposes only, they got over it fast. They handed me their babies, and everyone smiled. Babies slept in my lap while their mothers shook. It was actually quite peaceful, in a delirious way. Men were willing to dance, but the women had to dance.

When I fell asleep toward morning, I felt I had undergone initiation to life itself. Something had been cured.

Maps of Brazil reveal three north-eastern states that march horizontally across the country's shoulder: Ceará, Piauí, and Maranhão, all of which edge into the warm Atlantic just below the equator. The terrain is grandiose, magnificent, and complex. To travel in this New World is to see the America Amerigo saw. It looks and feels just as it would have five hundred years ago: wild, vigorous, open, and raw. There are lush tropical deltas, river crossings, and, most of all, beaches—mile upon mile of ocean and sand, miraculously uninfested by the commercial appetites of modern man. There are also poor farms, desert, the dry hinterlands that Brazilians call the Sertão. It is a thorny scrubland, its red soil baked as hard as a clay flowerpot. The parched heat seems to contribute to an almost permanent state of social distress. Periodic droughts have set off human stampedes of migration to the cities farther south; as much as eighty percent of the population has left in the past forty years.

Before we set out from Fortaleza, Senhor Ramos, our guide, spread the maps on the hood of the Land Rover that would be our headquarters for the next two weeks. We were an affable, multilingual lot: a photographer from New Zealand, a photo assistant from Argentina, and me. With very little idea of what to expect, our team set out to cross six hundred miles of open coast. All along the way, we would be hugging the shore, which meant we had to travel by four-wheel drive and boat. We would make our way from Fortaleza to Jericoacoara, a beachside outpost of relative modernity that is but a tiny point in 250 miles of open sand, and then from there to the delta of the Parnaíba River, the third-largest delta in the world, to Lençóis Maranhenses, a national dune park of unearthly grandeur, and end up in the colonial city of São Luís, the capital of Maranhão. Looking at the maps, things didn't seem that far apart. But traveling overland had a way of taking longer than expected.

Acidilio Ramos, who was assigned to us by Trip da Areia, a travel outfitter based in Fortaleza, is as dignified as a Portuguese count, with the mild and courteous disposition of an old scholar or a saint. He said he used to be a butcher before taking up guiding. An adulthood in the sun has cured his skin to something approaching moccasin. He is as laconic as a cowboy in a silent western. A bird and the shadow of the bird crossed the empty coastline, a huge white form and its black copy. "Garças," said Senhor Ramos. A few hours later, during a water break, he stooped on the damp sand and drew the webbed feet and enormous six-foot wingspan, and we settled on egret as the English translation.

Jericoacoara appeared on the horizon as a great elongated barrow rising above the flatland and the even flatter sea. In the middle of a white-hot afternoon, it was a long, low isosceles triangle of earth whose flock-nibbled grasses were the color of Andrew Wyeth's Pennsylvania landscapes. The name means "Crocodile Basking in the Sun," and that is precisely the impression it gives. Clearly the indigenous Tupi-Guarani peoples who settled it, who named it, must have felt its insistent power. The sea, now a bright magenta color, with plenty of whitecap foam—and the sound of the sea—was everywhere. The vehicle startled a flock of gulls or egrets. They rose and scattered in the energized atmosphere, like thoughts or words or emotion. As we approached, an approach that had taken all day, three Brazilians on horseback went by. They were smiling as if the daylight were comical.

The village was splayed out in the heat, living its siesta life forever. No more than a tiny cluster of homes, the community is only four streets wide. There are no paved roads, no streetlights, not even docks for the fishing fleet. The fishermen leave their boats tilted on the sand like those in a Van Gogh painting. The Vila Kalango was located just inside the tight perimeter, and we dropped our bags in the sand courtyard and were shown to the semi-detached brick and straw-thatch rooms. In the past twenty-five years, a small colony of canny European dropout capitalists have established enough of an infrastructure so that now, along the waterfront for maybe a hundred yards, the scene resembles a transplanted Mediterranean resort from about, say, 1927. There are three or four outdoor cafés, a few seafood restaurants, a couple of nightspots for music and dancing. In the sand alleys are a handful of surf shops and sunglass kiosks, but during our visit in June, the off-est of off-seasons, there were hardly any tourists about.

I grabbed a rucksack, field glasses, and a notebook and headed out for a quick reconnaissance of the immensity beyond town. Almost without knowing why, I began to walk uphill. The grasses seemed frail from a distance, but when I walked on them, they were incredibly tough, sewn onto the surface of the sand like hemp, or even wire. There were narrow tracks that were nothing but sand, so in a short while, I felt the climbing in my calf muscles and the front of the thighs. Up. Up. Here and there were enormous boulders, then sand clearings and cactus and shrikes perched on them, staring. In 1984, reacting intelligently to the overpowering beauty of the place, the Brazilian government declared Jeri and its surroundings to be an Environment Protection Area, safeguarding the treasure for all time.

Just below the summit, I settled down with my back to a boulder to pull out the binoculars and enjoy a slow pan. Tracking quietly over the unpopulated rough, I almost missed them—a small flock of miniature brown owls with enormous yellow eyes. Guarding the mouths of their burrows, they stared right at me, unblinking, with a resolute intensity, a glare to keep predators at bay. It was a fantastic standoff, a visual showdown.

With no shade to interfere, the descending sun exposed every feather, the ear tufts as they swiveled to listen to me, the tawny yellow claws. Their shanks were a creamy mahogany, the bodies a duff golden brown. If I were to name them, I would call them prairie dog owls since at first glance they looked exactly like the rocks they live among. It was wonderful just to be in this strange company at sunset on the coastline of America.

The horizon to the north became a white, wet, rumpled tin foil, a hammered sheen that magnified and scattered the horizontal rays of the now red sun. There was one flame dancing in every wave. And the dimming of the evening light didn't quite calm down the world here on the cliffs among the owls—if anything the night seemed to amplify the otherworldly sound. One by one the stars emerged, and soon they too were jumping on the face of the water, abundant as the whitecaps, like fireflies a million miles away. It was Nietzsche who prophesied that the earth itself would become a place of healing. There is a deep emotional cure to be had out here, far from the lights of any town, where, even at sea level, the Milky Way seemed to be an extension of the blown salt spray. Time didn't so much pass as dissolve.

The edge of town is where the poor people live. For the most part, they are farmers and fishermen, but many take advantage of the seasonal migration of European windsurfers and other tourists; they run little cement-porch restaurants. I pulled up short at a café with precisely one table. The stereo was blasting Bob Marley into the darkness: "My feet is my only carriage." I sat down and ordered precisely one beer. Before I could pay for it, mysteriously, Senhor Ramos drove by in the washed Land Rover. The café belonged to one of his friends. He introduced me. Smiles. Good feelings. The beer was free. Whenever I travel, I get this impression: Total strangers are your true family. Your family is everybody in the world.

In the morning, everywhere people were raking, sawing, fixing things. Fishermen stood near their beached boats, talking about this very day. One or two of them soundlessly set sail.

Senhor Ramos carried "Imagens de Sattélites," and combined them with tide charts to determine the best times to travel up the coast. The images looked like slides of human tissue under the microscope. They showed the green puckerbrush agricultural plains of the Nordeste, which are fissured with blue rivers: Rio Ubatuba, Rio Camurupim, Rio São Miguel, Rio Parnaíba. Also visible were the white fringes of sand, a substantial foam riding the long, sweeping wave of the land, beaches wide enough to be photographed from space. "Senhor Anthony," said Senhor Ramos, "they were formed four hundred million years ago. No matter what, they will be here four hundred million more after we are gone."

Midway between Jericoacoara and the city of São Luís, the Parnaíba Delta is an unspoiled ecosystem of rivers, mangrove swamps, islands, beaches, and sand dunes. It has the size and majesty of the Mississippi Delta without the urban infrastructure to foul it up. Senhor Ramos dropped us at its eastern edge. He would meet us later on the other side.

We picked up the boat—the equivalent of a small Boston Whaler, with an outboard motor and a canopy to shield us from the furnace sun—in a small riverside village called Araioses. The pilot steered us in and out among the infinite labyrinth of emerald channels. Two men in a dugout canoe were foraging for açaí, an Amazonian palm prized for its antioxidant fruit. Jungle vines closed in, trailing vegetation in the water lilies along the shore. The mud was watery like gruel, and the water was muddy like pea soup. Fish rose in lazy circles. The channel became narrower and narrower, until the boat was whispering among the shallow reeds. I waited for the anaconda to drop on my neck. Then we ran aground.

The river was a river no longer. The motor was switched off. The pilot handed us a line; we stripped to our shorts, hopped overboard, and began to drag our vessel downstream. Some people might find wading in tropical slop, with who knows what sluicing between bare toes, unnerving. The human male will do anything if someone else does it first. After a few hundred yards of wading and hauling, the stream grew deeper once again, and we hopped back in the boat.

Toward noon, halfway through our delta traverse, we rounded a wide sweeping bend. Suddenly, rising overhead behind the deep jungle canopy on the bank was a golden sand formation much larger than a dune. The sand glacier reached the shore, sloping into the water as if it, too, were thirsty and hot. Between the blue water and the long smooth golden wall was a one-hut hamlet, with a thin smoke column rising from a cooking fire. A man and a woman squatted near it, intently focused on mending their fishing nets. One child romped along the shore with his dog. With the ominous power of the marching motionless sand behind it, the scene looked like a poster designed to warn of global warming. It was a visible parable, concise and precise: Those who have eyes, let them see.

Still shaken by this close encounter, we pulled ashore for lunch at the delta version of a voyagers' rest stop: A thatched roof shaded a few benches and tables. There was a spigot for drinking water and a canteen. As we stretched our legs, I noticed a monkey chained to a stake in the yard. One of his relatives, still enjoying his freedom, was crouched on a low bough directly overhead, deconstructing a coconut with his slender fingers and sharp teeth. I sat with the two of them: three primates eating lunch.

I shared my sandwich with the prisoner, all the while entranced by the dexterity and focus of the one who was free. He worked with a quiet frenzy at his task, deliberate as he peeled the tough bark to get at the pure white meat inside. The drive, intensity, and even the malice in his energy reminded me of jungle behavior back home. He was only a few feet away, and the frankness of his gaze was unnerving. I was looking in a fur mirror, where intelligence and malevolence intertwined. When we finished our meal, I bowed to the monkey in the tree and climbed back into the boat.

The trip across the delta took five hours, but the lethargy induced by the tropical climate vanished once we found open water. The driver hit the throttle hard. For about six miles we crossed Tutóia Bay, with the Atlantic Ocean visible to the north. It was the great wide open, so clean even the mudflats were pure. There was no litter. Five razorbills squealed, left their fishing spots, and wheeled away. There were tropical flamingos so shockingly pink that they looked like lipstick, as well as plentiful oyster beds patrolled by great blue herons. We passed a solitary fisherman in his minuscule dinghy. The tea-colored sail was more patch than anything, a stained quilt of tears and repairs.

At Tutóia, a cluster of stuccoed houses in a palm grove, we soon spotted Senhor Ramos in his white Land Rover. In the dusk, we headed off for the tiny outpost of Caburé, where we were to spend the night.

The next morning at dawn, I was delighted to find that we were in a three-dwelling village, frail cabins on a spit of sand. I suppose it wouldn't be paradise if getting here were easy. Trees stood in the ocean. Black shorebirds called urubu breakfasted on shark. The Big Dipper hung upside down in the sky, as if it had been put back any which way after serving the rice for supper. After last night's strange, soundless thunderstorm, hermit crabs were rebuilding their tunnels, grain by grain. Four-eyed silver fish skipped away from the shore, like stones thrown by invisible children. Goats grazed in the salty bracken, tended by no one.

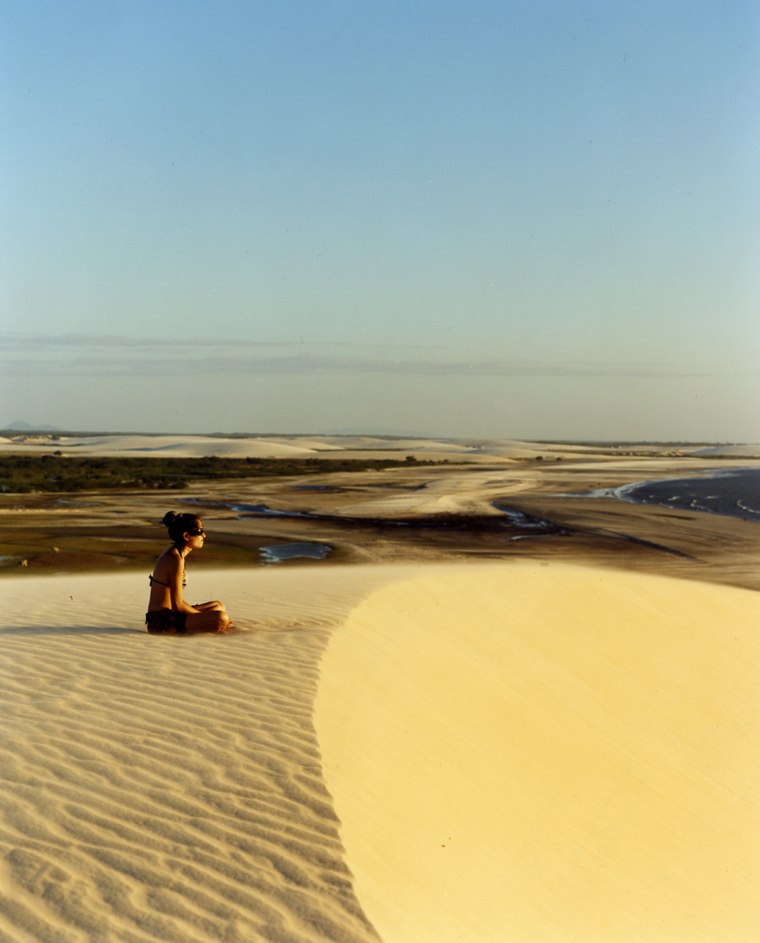

The Parque Nacional dos Lençóis Maranhenses is about the size of Rhode Island, forty miles by seventy, and composed entirely of sand dunes a hundred feet high. The geography here in early June is like nothing else on earth, because the rainy season fills every trough with water and the world becomes some kind of perfect contradiction of itself: like an M. C. Escher print, it is either a drowned desert or a sandy lake, depending on how the mind's eye frames what it is seeing. The pools carved into the sand fill with a green, earth-colored water, which in turn reflects the blue sky. Great white birds coast through, keeping their opinions to themselves. Their stark shadows seem as substantial as the mysterious creatures themselves. There are blown-grit walls ten stories high, on which fair-weather cirrus clouds trace their patterns as they comb the sky.

An egret cried in the starkness. It was the only sound I heard for an hour. One grass stalk emerged, thirty feet up the side of a dune, and the single blade tilted there, twitching in the relentless breeze. You can watch your own mind flounder for meaning. Clouds formed like thoughts in the soundlessness. They drifted, and as they passed over the oven hills, I could feel them as patches of low temperature. The stark purity of the landscape reduces the world to you and earth. The deprivation intensifies what remains. I walked for a while, and then I ran.

Since the wind erases your footsteps every four minutes, I used the jade-colored pools like Hansel and Gretel's breadcrumbs, passing from one unique shape to the next so as to be able to find my way back after an hour. Sand conditions vary just as snow does in the mountains. Ocean breezes can harden the windward form into a solid pack and reduce other sections to an ankle-deep powder. Eventually I got to the sea. It seemed odd to have traveled so far and worked so hard to reach the ordinary. When you achieve the outermost space, there is nowhere to go but home again.

From the park to São Luís is a nine-hour drive through arid country. There is a popular literature that celebrates the local cow-punching outlaws, but none of them are around today. The yards are sun-pounded sand. Here and there someone waters a bush. You expect to hear the droplets sizzle as they land, like butter in a frying pan. Bundles of dry wood are for sale by the road. Either ghosts are cooking or someone wants the furnace of the afternoon to be a touch hotter. I tried to imagine life here. It would be like living in a hay bale. A cream-colored, bell-wearing bull was placidly chewing his cud, straddling the yellow line in the middle of the highway. Why not? It is a road with no travelers.

We stopped for refreshments exactly once. Senhor Ramos beheaded a coconut. He inserted a straw and handed it to me: how odd to be drinking a tree.

I was grateful and relieved that the climate was luscious in São Luís. There is so much vegetation here, even in this ancient colonial town, so much water in the air, that a second canopy of green emerges from the steeples of Sanctae Mariae de Victoria, just across the street from my room. Moss gives way to grasses, which in turn spawn vines, and now the highest feature of the 1629 church is not the cross but a layer of ten-foot trees that stand out like a jungle frieze, a great hanging garden against the skyline. The fragrant green petals were whistling as they stirred in a breeze off the Baía de São Marcos.

This is the only city in Brazil founded by the French, who landed in 1612 and were driven out three years later by the Portuguese. The port generated fabulous wealth from the cotton and sugar trades, which relied entirely on slave labor. When Brazil abolished slavery in 1888, the wealth was abolished with it. The island city sank into a hundred years of long, slow decline. Only recently, with the awarding of UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 1997, has the halting work of restoration begun.

It is the refurbished colonial neighborhoods with their market plazas, Catholic churches, and gleaming white government forts that are now the showpiece of the city. Workers keep the narrow alleyways and winding stairs swept for tourists, but the desiccated landscapes of the Sertao that surround the city remind a visitor of the all too frequent tendency of human beings to ravage and then abandon their land.

The Pousada Portas da Amazônia, in the historic district, is a beautiful example of architectural recycling, a small hotel in a former colonial town house. My wide, silent, and all-white room had three floor-to-ceiling French windows facing the Rio Mearim. The polished planks of the antique floorboards gleamed. The maze at the heart of the old city is miraculously car-free, so you can actually hear scraps of conversation, crockery, whistling from the narrow alleys below. Bleached laundry hangs drying from the balconies. The cleaned and restored facades of the buildings are covered with azulejos, blue-white ceramic tiles.

Most buildings have been painted in historically accurate colors, but these colors were constantly being reworked by the weather. The surfaces were saturated by the nearby sea. Plaster had corroded, chunky patches had fallen away, revealing even lovelier tones beneath. Degas labored for years to get this ripeness into his pastels, a luxuriant ocher, saffron, yeast. Most of the streets are interrupted by sets of stairs. Since the city is also an island, at the top of every staircase is an ocean or a river view.

Here, too, there was dancing almost every night. June is the month of Bumba-Meu-Boi, an extravagant fusion of the Catholic feast day of Saint John (São João), African music, and Brazilian colonial history. Bumba comes from the Portuguese verb bumbar: to beat against, as a storm wave beats the coast, or an enslaved people rumble against their oppression, or an entranced drummer pounds. Boi is an ox or a bull. The tale—equal parts comedy and tragedy, native and European, slave and free—involves the death and magical resurrection of the landowner's prized bull. Fires had been lit in the alleys, and men clustered near them, heating and tightening the skins of their enormous bongos. In the shaded streets of Rua de Estrela and Rua da Fandega, the cafés had set up chairs and tables in the road. The neighborhood was full. Village companies from throughout Maranhão had arrived in the capital city to perform.

The whole celebration is a fusion of human and animal energies; the men are horses and soldiers and bulls, the women birds. Dozens of dancers parade through the town, then re-enact the story in a cobblestoned square. Scenes are narrated by a master of ceremonies who misses no opportunity to satirize the slave owner and glamorize the farmer and his lovely daughter. Everyone knows the words to the songs, and at every chorus the entire city seems to join in. In the humid night, a sweat sheen coats every breast and every thigh. The whole performance is a trance, an hours-long nighttime woken dream.

Having traveled several thousand miles to explore an empty coastline, it was disconcerting to keep ending up at concerts. But the dances turned out to have been an initiation as well as a reintegration. The veil between audience and performers had worn thin. Step by step, the great coast works its way inside you and becomes a state of mind. Without intending to, almost against my will, the dancers implied that nature and human nature are two features of the same condition. The fluctuations of the tides and the flexibility of the bodies are each in their own way expressions of a totality that is ultimately benign. Dances and long walks both mark time.

With all our current obsession about global warming, the first thing we have to cool off is the mind. Ocean, trade winds, deltas, estuaries, rivers, great clouds of galaxies—I had a chance to glimpse what planet earth herself has in mind. The form of it, the shapely, comely, erotic power of it all, generates a longing to treat it as you would your own daughter, with gentleness and tenderness and reverence and respect.

The three provinces on the northeast coast of Brazil—Ceará, Maranhão, and Piauí—are largely agricultural, with scattered pockets of development. Traveling toward the extraordinary beaches is erratic and challenging; deeply rutted sand tracks wind among palm groves and dunes. Multiple river crossings, rain squalls, and even high tide can turn a few miles as the crow flies into a half-day expedition.

The very remoteness and wildness that make this coast so appealing also mean that there are fewer of the amenities associated with modern tourism. This is a good thing. Usually even the most humble local pousada, if it is located in an isolated spot, will have a restaurant attached.

High season in Ceará and Piauí is generally December through February, when the European windsurfing contingent descends on Jericoacoara. Maranhão is best right after the rainy season—which typically ends in May—when the spaces between the dunes of Lençóis Maranhenses National Park are full of clear freshwater.

The country code is 55. Prices quoted are for May 2008.

designs customized tours with knowledgeable and resourceful local guides like Acidilio Ramos (81-9999-6660; 9-day custom tours from about $5,000 per person). Ramos also works with Camel Tour Turismo Off Road, which specializes in coastal trips, has a fleet of comfortable and reliable Land Rovers, and will arrange activities like birding, horseback riding, and windsurfing (85-3485-4822; cameltour.com.br; 7-day Lençóis Maran-henses trip, $3,550 per person).

Ceará

A magnet for European windsurfing fanatics—owing to trade winds that develop punctually by midmorning and blast steadily well past sundown—the state is known for its magnificent beaches, which run uninterrupted from Fortaleza to the Parnaíba Delta. The modern capital city of Fortaleza has many slick comforts and is a popular entry point to the northeast coast, with flights from Brazilian and European hubs. The Hotel Luzeiros, across from the waterfront, has clean, well-appointed rooms with AC and a pool. The higher floors have ocean views (85-4006-8586; doubles, $150–$168).

The pleasant village of Flexeiras, about 90 miles west, has become a favorite escape for Fortaleza residents, who come for the stunning beaches and upscale resorts. The best of these is the 24-room Rede Beach Resort, which, in addition to virgin coastline, has a spa, tennis courts, and an excellent oceanfront restaurant (85-9198-3635; doubles, $92–$102; entrées for two, $15–$30).

Jericoacoara, or "Jeri," a village in an environmentally protected enclave 200 miles west of Fortaleza, began luring sophisticates more than a decade ago. It recently acquired electricity, but still the streets are sand, fishing is the basis of the economy, and farm animals roam freely. The best lodging is at Vila Kalango, a remarkable cross between Swiss Family Robinson and Restoration Hardware. Set in a coconut grove at the edge of the sea, the rooms are a series of isolated brick towers with thatched roofs, wood floors, ceiling fans, and modern plumbing. There is a swimming pool, a windsurf rental shop, and a herd of horses in the corral (88-3669-2289; doubles, $123–$240). The beach at the rustic village of Preá, just 15 minutes east of Jeri, is famous for its perfect windsurfing conditions. Access requires a dune buggy or a jeep.

Maranhão

Anchored by the gateway city of São Luís, Maranhão is known mostly for the fantastical Lençóis Maranhenses National Park. The restored Portas da Amazónia is an early-19th-century inn with modern conveniences that do not interfere with its simple, dignified charm. In June, the high-water mark of cultural festivities, there's nightly African drumming. The courtyard restaurant serves a lavish Brazilian breakfast (98-3222-9937; doubles, $82–$110).

Tiny and remote Caburé, between Lençóis Maranhenses and Parnaíba Delta, is accessible only by boat. With the Rio Preguiças on one side and the Atlantic on the other, it is a sand-spit intersection that seems completely disconnected from civilization. The wide-open is a rustic resort—no phones, no TV—with eight cabins, each with a porch and a hammock, and a great outdoor restaurant serving the day's catch (98-3349-1338; doubles, $110; entrées for two, $12–$22).

It's a long jeep ride through rugged, swampy terrain to get to Lençóis Maranhenses National Park—1,200 square miles of towering dunes and in May and June, clear freshwater lakes. No vehicles are allowed in the park, so all exploring must be done on foot. Bring water, sunscreen, and protective clothing. Stay nearby, in the river port of Barreirinhas, which has an ample supply of inexpensive pousadas. About a mile outside the village, the , set in a grove of carnauba trees on the bank of the Preguiças, has a huge pool, a very sophisticated restaurant, ceiling fans, AC, and even a chapel should you feel guilty about the luxurious conditions in which you find yourself (98-3349-6050; doubles, $170; entrées, $10–$14).

Piauí

One of only three deltas in the Americas that empty into the ocean, is a pristine ecosystem with tropical vegetation, immense dunes, open bays, and tiny streams. Most tours are done in small, canopied motorboats that can access even the most shallow riverbeds; (half-day tours, $175 per person). The closest lodgings are in Parnaíba, a gritty colonial city populated largely with displaced agricultural workers. The serviceable Hotel Islamar has AC, helpful staff, and a good restaurant (86-3366-1165; doubles, $175–$350; entrées, $8–$12).