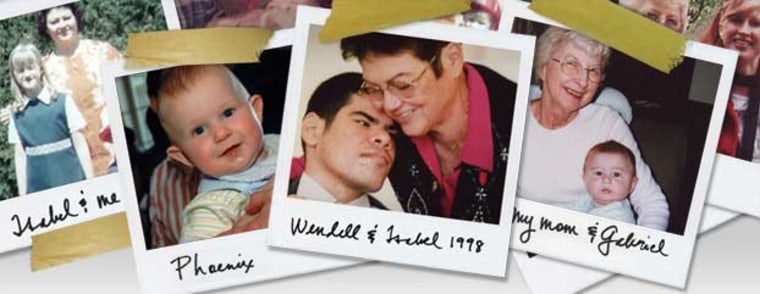

More than 40 years ago, my mother and one of her best friends struck an unconventional deal: They would share me.

My mom, Beth Dahlstrom, met Isabel Peterson when they were both nurses at a Southern California hospital. They became even closer friends when both became pregnant with their first child in their late 30s, later in life than many women at the time, and gave birth the same year.

I was 5 months old in July 1967 when Isabel’s son, Wendell, was born. My mom still cries when she recounts that phone call. Something was wrong with the baby, Isabel told her. He’d been having convulsions and was severely brain damaged. The doctors didn’t expect him to live.

“She was crying and I was crying and I said, ‘We’ll share Linda with you,’” my mom would later tell me. “I couldn’t imagine losing you, or truly knowing Isabel’s pain — the only thing I had to offer was sharing you.”

From that moment and through all the years since, Isabel has been my “other mother.” She’s always loved me in the deep, completely-in-your-corner, unconditional and yet no-nonsense way that great mothers do.

As a child, I played in the lemon grove behind her house, tussled with her dog and looked up to her stepchildren, LaDona, Scott and Greg, who were older and seemed so much more sophisticated. If I got frustrated with my parents, I’d threaten to go live with Isabel.

Years later, after my family moved to another state, she made my favorite chocolate chip oatmeal cookies and mailed them to my college. Later still, when my mother was battling breast cancer and my father was dying of heart disease, Isabel sought me out to remind me she was still here; I could count on her.

Our relationship has changed from my being her little girl into one of adult friendship as we've navigated life’s turns. And more recently, Isabel and I have become bound by something else — we’ve each learned what it means for a mother to lose a child.

A world upside down

Like Isabel and my mother, I also did not have my first child until my late 30s. Phoenix was a joyful, curious and gregarious little boy who loved to cuddle and be read to and who seemed so eager to embrace the world he’d come into.

But on July 7, 2005, when Phoenix was 7 months old, I woke in the dark to hear him making low moaning sounds. My husband, Mike, swept our son into his arms as I leapt for the thermometer. His fever was 102.

Even though we suspected we were overreacting, we headed straight to the emergency room. Phoenix, strong and sturdy, had always been astoundingly healthy; while his baby friends seemed to catch regular colds and flus, he’d never even had so much as the sniffles.

In the emergency room, the doctor diagnosed him with the flu and sent us home. But a few hours later he seemed worse, so we took him to his pediatrician. In her office, Phoenix suddenly went limp.

I could barely breathe when the doctor pulled up his shirt and revealed a sudden rash that indicated bacterial meningitis, a rare but deadly infection of the brain and spinal cord that kills 10 percent of those it strikes.

That was the last moment of the life I had known.

Phoenix died two hours later, surrounded by hospital staff administering CPR as my husband and I sang lullabies to him, stroked his head and begged him not to leave us.

The instant Phoenix died, I tried to will my body to go with him. I didn’t want to be here without him. Years ago, a professor and father of two told me a parent’s main job is simply to protect and keep your child safe. At that, I had failed.

In the hours after Phoenix died, as I held his body in the twilight of the hospital room, I stripped off his clothes and pressed him against the skin of my stomach, trying to infuse my life into him, trade my life for his. To bring him back.

Phoenix was with God, I knew. Ultimately he was OK. But I was in agony.

In the months that followed, sometimes I was certain I heard him cooing in another part of the house and went looking for him. I thought I might be going crazy and wondered what would be better — to be insane and think he was still alive or to be lucid and know he wasn’t?

During the infrequent nights I slept, I always dreamed I was trying to save him. In some dreams he was brain damaged. In others his limbs were twisted. I woke from one horror into a worse one.

Those who do survive bacterial meningitis often suffer catastrophic injuries. Many lose limbs and are mentally impaired. When a nurse suggested that perhaps it was better he had died, I told her I would have given anything to have Phoenix in any condition. It might have been harder for my vibrant, joyful son if he had survived — but easier for me, I told her.

“Maybe at first,” she said. “But not later on.”

But truly loving your child unconditionally, I knew, meant loving him fiercely in whatever state he’s in. Isabel had shown me that.

The color of a mother's love

Wendell did not die when he was a baby as doctors had predicted. Isabel fought to bring him home, despite their recommendations that she put him in a facility. He would never learn to talk, walk or sit up by himself. The doctors warned Isabel and her husband, Joel, that Wendell would probably never even recognize them. None of that tempered Isabel’s love for her son.

“He was a joy to care for, he was just a darling little boy,” she says.

When he was 3, and still only had the motor skills of an infant, he became too big for Isabel to care for at home. He was moved to Fairview Developmental Center where Isabel knew her growing son would get the care she could no longer provide. She nearly moved in too. “I couldn’t stay away,” she said. “I always had to see him.”

If I was in California visiting Isabel, I’d go with her. Her routine for decades was to bring him his favorite foods, pureed, for lunch, along with his favorite kinds of ice cream for dessert. She always seemed as excited to see Wendell as if she were reuniting with a long-lost love. Her pace would quicken as she got closer to his room.

From the hallway, she’d call out, “Hello, Angel, I’m here,” and this young man, who supposedly was never to recognize his mother, would beam and turn his face to her like she was the sun. She rocked him in her lap, which she knew he loved, until she was in her late 60s and physically couldn’t bear the weight.

“Isn’t he beautiful?,” Isabel would always say, seeming never to see his twisted limbs.

As a mother, love washes over and colors everything that has to do with your child. You find strength in yourself to do things you never could have imagined, whether it’s changing the dirtiest diaper or giving a eulogy standing in front of a miniature casket. You do whatever is required to take care of your child.

An unstoppable force

Moments after Phoenix died, my mother arrived at the hospital. She brushed past nurses who tried to insist that she put on protective clothing and a mask to protect her from the infectious disease that had killed Phoenix because she knew I needed her. My mother is in her 70s, a gentle, elegant slip of a woman, but she is a lioness when it comes to taking care of her family.

Mike and I stayed with her for weeks, unable to face our house without Phoenix. Some nights, when I couldn’t sleep, I crawled into bed beside her, like I did as a child when I had a nightmare. She hosted the many friends who formed a net of support around us, made our favorite foods, tried to coax me into eating and spent hours telling Mike and me what good parents we’d been to her only grandchild.

If watching your child die is the worst agony one can experience, I’m sure seeing your child suffer is close behind it.

As I disappeared into the abyss of grief, I stopped returning phone calls and e-mails, some days unable to muster the energy or clarity of mind to put together a sentence. But Isabel, unwavering and undemanding, sent into the silence a stream of cards and letters telling me she loved me and was praying for me. In many of them, she recounted the comforting story of us: “I remember the day your mother asked if I wanted to share you …” Always she signed her letters, “Love, Your other mother.”

In time, very slowly, I began to come back to life. I didn’t want the legacy of my beautiful, sparkly, happy boy to be that his life and death had destroyed his family. He deserved better than that. Eventually, I resolved to find a way to go forward in a manner that honored his spirit as well as my own. Three years later, I’m still finding my way. I suspect I will for the rest of my life. You never get over the death of a child, say those in the community of bereaved parents my husband and I are now a part of. But you can find a way to integrate that loss. You can learn to live with it as a part of you.

Goodbye to Wendell

At the end of January, Wendell was diagnosed with advanced cancer; doctors only gave him two weeks to live. This time, they were right.

He died on Feb. 15, 2008, at the age of 40 with his family and the staff who’d lovingly taken care of him for years at his side.

Whether your child lives seven months and four days, as Phoenix did, or 40 years and six months, like Wendell, it hurts the same. We always want more time.

“It’s not possible to love your child any more than you do at the time they die,” explained a friend, whose own son died as a teenager.

The little square of grass on a hillside where Phoenix is buried is to me the most precious patch of land I know. My husband and I helped bury him ourselves, letting the dirt run through our fingers as we tossed handfuls on to his casket.

We tend his grave about every two weeks, often with our precious 15-month old, Gabriel, who shares Phoenix’s blond hair, infectious energy and love of dogs and just about anyone who gives him a smile. Gabriel plays with the trains and other little toys left next to the headstone that bears his brother’s handprint while Mike and I water the flowers, a last way to honor him.

Before I had Phoenix, everyone told me how much my life would change. I’d never get a full night’s sleep again, friends predicted. My schedule would no longer be my own and my house would be transformed into a giant toy box, they warned. But the true way becoming a mother changes you, I’ve learned, is that your heart opens wider than ever before.

Phoenix would be almost 3 and a half now had he lived. I had him for such a short time but I got to love and take care of him for his whole lifetime. And I will be his mother for the rest of mine. That is a tremendous gift I wouldn’t have missed for the world.

When I called Isabel last week, I accidentally woke her from an afternoon nap, a rare occurrence. When Wendell was alive, if she ever had a spare moment she spent it visiting him. But now the woman who I always knew to be everyone’s anchor felt unmoored. And, as the days passed, she felt sadder.

Mark Twain, whose daughter died of meningitis, said losing a child is like your house burning down. At first you’re crushed by the calamity that the house is gone. And then, over the months and years to follow, you remember all the precious and irreplaceable things that were found only in that house. The ripples of grief stretch out of sight.

After Wendell died, Isabel was filled with gratitude that he had lived as long as he did, and that the end, when it came, was swift and he didn’t suffer. But lately she couldn’t stop crying. “How long did you cry after Phoenix died?” she asked.

At first I didn’t want to tell her that I cried daily for at least the first year — and after that only slightly less frequently. Grief evolves over time, but doesn’t necessarily ebb.

But these days, I told her, I also feel joy and excitement again. The complicated truth is that the happiness over having had these amazing boys in our lives at all can exist right alongside the sadness that they are gone. It is possible to feel both things at exactly the same time without one canceling the other out. They are both equal parts in the fullness of a mother’s love.