The highly publicized releases of "UFO files" from France and Britain provide more puzzling tales about anomalous aerial objects over the years. But the stories behind some of the most spectacular sightings in UFO history will come to light only when the Russian Ministry of Defense opens up its files.

Consider one of the most sensational UFO stories in Soviet history — a story that has been enshrined in world "ufology" as a classic that cannot be explained in any prosaic terms.

The tale of the Minsk UFO sighting can teach a lesson about the vigor of unidentified flying objects as a cultural phenomenon.

A passenger jet is flying north on Sept. 7, 1984, near Minsk, in present-day Belarus. Suddenly, at 4:10 a.m., the flight crew notices a glowing object out their forward right window. In the 10 minutes that follow, the object changes shape, zooms in on the aircraft, plays searchlights on the ground beneath it, and envelops the airliner in a mysterious ray of light that fatally injures one of the pilots. Other aircraft in the area, alerted by air traffic control operators who are watching the UFO on radar, also see it.

The incident figures prominently in "UFO Chronicles of the Soviet Union," a 1992 book by Jacques Vallee, who was the real-life inspiration for the fictional ufologist in the movie "Close Encounters of the Third Kind."

“No natural explanation [is] possible, given the evidence,” Vallee wrote.

A leading Russian UFO expert, Vladimir Azhazha, reported that as a result of the encounter the co-pilot “had a serious mental derangement — the encephalogram of his brain was not of an ‘earthly’ character, as he lost memory for long periods of time.”

This combination of perceptions from multiple witnesses and sensors, together with the serious physiological effects, makes for a dramatic event that on the face of it defies any earthly explanation. It was just as amazing that the official Soviet news media, long averse to discussing UFO subjects, disclosed the story in the first place. So it was no mystery that over the years that followed, the story was never actually checked out. It was only retold again and again.

Weighing the pilots' evidence

However much we are comfortable in entrusting our lives to airline pilots, a blind trust in their abilities as trained observers of aerial phenomena is sometimes a stretch. For a number of excellent and honorable reasons, pilots have often been known to overinterpret unusual visual phenomena, particularly when it comes to underestimating the distance from what look like other aircraft.

Think of it this way: You want the person at the front of the plane to be hair-trigger alert for visual cues to potential collisions, so avoidance maneuvers can be performed in time. The worst-case interpretation of perceptions is actually a plus.

So it’s no surprise that pilots have sent their planes into a dive to duck under a fireball meteor that was really 50 miles away, or have dodged a flaming falling satellite passing 60 miles overhead. Even celestial objects are misperceived by pilots more frequently than by any other category of witness, UFO investigator J. Allen Hynek concluded 30 years ago. Since the outcome of a false-negative assessment (that is, being closer than assumed) could be death, and the cost of a false positive (being much farther away) is mere embarrassment, the bias of these reactions makes perfect sense.

What could have caused it?

Was there anything else in the sky that morning that the Soviet pilots might have seen? This wasn’t an easy question, since the Moscow press reports neglected to give the exact date of the event, but I could figure it out by checking Aeroflot airline schedules.

It turned out that early risers in Sweden and Finland had also seen an astonishing apparition in the sky that morning. According to reports collected by Claus Svahn of UFO-Sweden, people called in accounts of seeing "a very strong globe of light," sometimes "with a skirt under it." The light's glow was reflected off the ground and lasted for several minutes. In Finland, a UFO research club's annual report later cataloged 15 similar sightings from that country.

The immediate disconnect that I found was that the Scandinavian witnesses were not looking southeast, toward Minsk and the nearby airliner with its terrified crew. Nor were they looking eastward, toward the top-secret Russian space base at Plesetsk, where launchings sparked UFO reports starting in the mid-1960s. They were looking to the northeast, across Karelia and perhaps farther.

The direction of the apparition being seen simultaneously near Minsk provided another "look angle." If the vectors of the eyewitnesses are plotted on a map, they tend to converge out over the Barents Sea, far from land. This made the triggering mechanism for the sightings — assuming they were all of the same phenomenon — even more extraordinary.

Preludes and precedents

Whatever the stimulus behind the 1984 Minsk airliner story turned out to be, I already knew that many famous Soviet UFO reports were connected with secret military aerospace activities that were misperceived by ordinary citizens. I’ve posted several decades of such research results on my Web site.

In 1967, waves of UFO reports from southern Russia and a temporary period of official permission for public discussion created a "perfect storm" of Soviet UFO enthusiasm. But it was short-lived — the topic was soon forbidden again, possibly because the government realized that what was being seen and publicized was actually a series of top-secret space-to-ground nuclear warhead tests, a weapon Moscow had just signed an international space treaty to outlaw.

Once the Plesetsk Cosmodrome (south of Arkhangelsk) began launching satellites in 1966, skywatchers throughout the northwestern Soviet Union began seeing vast glowing clouds and lights moving through the skies. These were officially non-existent rocket launchings. "Not ours!” the officials seemed to be saying. "Must be Martians."

Other space events that sparked UFO reports included orbital rocket firings timed to occur while in direct radio contact with the main Soviet tracking site in the Crimea. Such firings and the subsequent expanding clouds of jettisoned surplus fuel weren't confined to Soviet airspace. One particular category of Soviet communications satellites performed the maneuver over the Andes Mountains, subjecting the southern tip of South America to UFO panics every year or two for decades.

As the Soviet Union lurched toward collapse in the 1980s, its rigid control over the press decayed. This allowed local newspapers, especially in the area of the Plesetsk space base, to begin publishing eyewitness accounts of correctly identified rocket launchings. The newspapers sometimes printed detailed drawings of the shifting shapes of the light show caused by the sequence of rocket stage firings and equipment ejections.

The evidence comes together

Still, I wasn't willing to wave off the elaborate extra dimensions of the Minsk UFO case as mere misperception and exaggerated coincidences. Even though none of the most exciting stories, such as one pilot's death half a year later from cancer, could ever be traced to any original firsthand sources, they made for a compelling narrative.

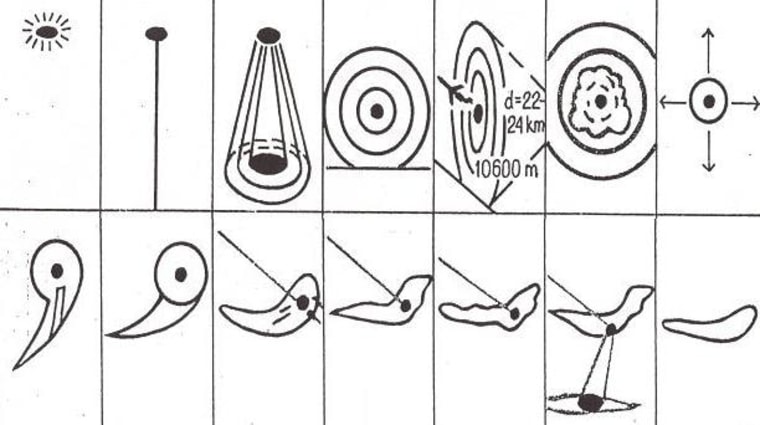

Fortunately, the Soviet collapse provided the opening for the collapse of the UFO story. The May-June 1991 issue of the magazine Science in the USSR contained an article that reprised the story with one stunning addendum from the co-pilot’s flight log. He had sketched the apparition, minute by minute, as it changed shape out his side of the cockpit window, and 14 of the drawings were published for the first (and as far as I can tell, only) time.

The graphic sequence of bright light, rays, expanding halos, misty cloudiness, tadpole tail and sudden linear streamers may have looked bizarre to the magazine’s readers. But they looked very familiar to me.

I dug out the clippings from Arkhangelsk newspapers that had been mailed to me by an associate there. I looked up the other articles from recent Moscow science magazines that showed how beautiful these rocket launches looked. I also found the set of sketches made by a witness in Sweden of what was immediately recognized as a rocket launch. I laid the separate sketches out on a table.

They all clearly showed the same sequence of shape-shifting visions, as viewed from different angles to the rear of the object’s flight. The more recent accounts were of nighttime missile launches — and the impression was overwhelming that the Minsk UFO, as drawn in real time by one of the primary witnesses, looked and changed just like them.

Case closed?

Without the detailed minute-by-minute drawings, any claim for solving the case would have been tentative, and circumstantial at best. Even now, the case isn't quite closed. Until the Russians release the records for the test launch of a submarine-based missile — as we now know often happened from that region of the ocean, but without official acknowledgement — the answer to the mystery will remain technically unproven.

But the answer is strong enough to remind us of wider principles of investigating — and evaluating — similar stories from around the world: There are more potential prosaic stimuli out there than we usually expect. Precise times and locations and viewing directions are critical to an investigation. The temptation to fall into excitable overinterpretation is almost irresistible. Myriads of weird but meaningless coincidences can be combined to embellish a good story.

The most important factors for cutting through the misperceptions would be having the good fortune to come across enough original evidence, and having enough time to make sense of that evidence. That’s one of the biggest lessons to be learned from the Minsk UFO case: As long as those factors are in short supply, it’s no mystery why there are so many amazing UFO stories — and so many enthusiasts willing to endorse them.

James Oberg, space analyst for NBC News, spent 22 years at the Johnson Space Center as a Mission Control operator and an orbital designer. He is the author of several books about the U.S. and Soviet space efforts, including "Red Star in Orbit" and "Uncovering Soviet Disasters."