This month the American Psychiatric Association announced the names of “working group” members who will guide the development of the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, the codex of American psychiatry.

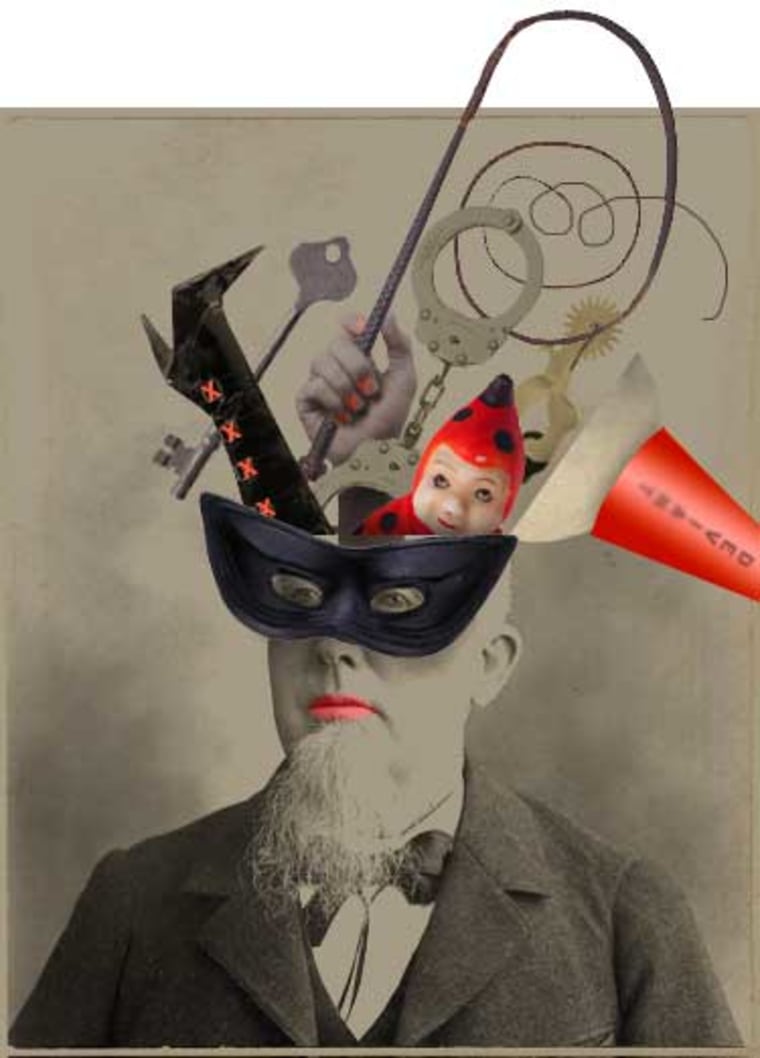

Not surprisingly, given the DSM’s colorful history, particularly when it comes to sex, controversy erupted within days of the announcement, especially over membership of the Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders working group, which will wrestle with questions such as: Are sadomasochism or pedophilia mental disorders? Are dysfunctions like female hypoactive sexual desire disorder (low sex drive) psychiatric issues, or hormonal issues? Perhaps the most important question is whether, when it comes to many sexual interests and issues, it’s even possible or desirable to create diagnostic criteria.

At least one petition, spearheaded by transgender activists, is being circulated to oppose the appointment of some members to the Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders work group and its chair, Kenneth Zucker, head of the Gender Identity Service at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada. The petition accuses Zucker of having engaged in “junk science” and promoting “hurtful theories” during his career, especially advocating the idea that children who are unambiguously male or female anatomically, but seem confused about their gender identity, can be treated by encouraging gender expression in line with their anatomy.

Zucker rejects the junk-science charge, saying that there “has to be an empirical basis to modify anything” in the DSM. As for hurting people, “in my own career, my primary motivation in working with children, adolescents and families is to help them with the distress and suffering they are experiencing, whatever the reasons they are having these struggles. I want to help people feel better about themselves, not hurt them.”

That sex is controversial comes as no surprise to Dr. Darrel Regier, the vice-chair of the APA’s DSM-V Task Force, based in Arlington, Va.

Sex, he says, in an understatement, “is an area that obviously has lots of emotion attached to it.” But the APA, he says, is doing its best to put science and evidence first, both in who it appoints to working groups and in the process it will use to create the DSM-V (so called because it is the fifth complete version). Each working group will accept input from many experts with varying views, reach a consensus on DSM content, and then put that work group’s product before the board of trustees of the APA and the APA assembly.

All that may be true, but Regier does not expect such reassurances to quell the forces already swirling around the DSM-V as it moves toward a 2012 publication date. Currently, the DSM-IV includes sex-related activities as varied as paraphilias like voyeurism, klismaphilia (erotic use of enemas) and sadism, and functional disorders like dyspareunia (pain with intercourse), erectile disorders and premature ejaculation.

'A set of scientific hypotheses'

The first DSM was issued in 1952. The idea was to create a more standardized way of talking about psychiatric disorders. As psychiatrist Dr. Gail Saltz, a TODAY Show contributor who also practices in New York, explains, the DSM is best viewed as “a language we have chosen to speak, a talking point we mental health professionals have created to communicate as well as we can with each other and with other professions.”

It is not a final arbiter of who’s crazy and who’s not. Saltz, who says she thinks the DSM can be limiting in clinical practice, prefers to take a holistic approach and look at each patient’s collection of symptoms and concerns without being restricted by the DSM’s various criteria.

Regier agrees that’s how doctors should use it, arguing that the DSM “really needs to be seen as a set of scientific hypotheses.” It is, he believes, “a living document” changeable with new research.

But if the DSM is a book of “hypotheses,” why the fuss? Does the DSM matter?

Yes. A lot.

The first reason why is prosaic. If you want your insurance to reimburse your visit to a mental health professional, you are probably going to need a DSM code signifying a diagnosis.

But the more profound reason is that it shapes how doctors, even the rest of rest of society, view sexuality.

“A psychiatric diagnosis is more than shorthand to facilitate communication among professionals or to standardize research parameters,” wrote Dr. Charles Moser and Peggy Kleinplatz in a 2005 paper published in the Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. “Psychiatric diagnoses affect child custody decisions, self-esteem, whether individuals are hired or fired, receive security clearances, or have other rights and privileges curtailed. Criminals may find that their sentences are either mitigated or enhanced as a direct result of their diagnoses. The equating of unusual sexual interests with psychiatric diagnoses has been used to justify the oppression of sexual minorities and to serve political agendas. A review of this area is not only a scientific issue, but also a human rights issue.”

A problem for whom? There is no shortage of opinion on what ought to be changed, deleted or included in the new DSM-V. Sandra Leiblum, formerly a professor at New Jersey’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and an expert in female sexual health who is now in private practice in Bridgewater, N.J., says she wants to see a revision of diagnoses of female hypoactive sexual desire disorder, other female arousal disorders and sexual pain like dyspareunia. For example, she wants language that would separate arousal disorders into genital (more biological in origin) and subjective subtypes.

Carol Queen, a sexologist, sexual rights activist and co-founder of San Francisco’s Center for Sex and Culture, believes the new DSM should stress that sexual variances are only a problem “if they are problems in the life of the person showing up” in a psychiatrist’s office “so that when somebody is eroticizing something, or doing something in a consensual way, that’s not a problem” even if it may seem odd to most of us.

She also proposes an addition, a diagnosis of “absexual” (“ab” meaning “away from”). This would include those who appear to be “turned on by fulminating against it.” Examples could include state governors who crusade against prostitution even while paying hookers for sex, and religious leaders who wind up trying to explain engaging in the sex acts they preach against.

Moser, who is affiliated with the Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality in San Francisco, and Kleinplatz, from the University of Ottawa, argue that all paraphilias, like sexual sadism, sexual masochism, transvestism, should be removed from the DSM, insisting that “the DSM criteria for diagnosis of unusual sexual interests as pathological rests on a series of unproven and more importantly, untested assumptions.”

This does not mean, as opponents of this idea have suggested, that they somehow approve of sex between adults and children. “We would argue that the removal of pedophilia from the DSM would focus attention on the criminal aspect of these acts, and not allow the perpetrators to claim mental illness as a defense or use it to mitigate responsibility for their crimes," they wrote. "Individuals convicted of these crimes should be punished as provided by the laws in the jurisdiction in which the crime occurred.”

Most of these suggestions are inherently political, as much as the APA and most psychiatrists would wish to avoid politics. Sex exists as part of the culture, and it cannot be separated from it.

The DSM has reflected cultural shifts through its revisions and new editions. The most famous example is homosexuality. When the first DSM was created in 1952, homosexuality was declared a mental illness. By 1973, and after much heated debate and over objections from religious conservatives, the DSM-II excluded homosexuality as a disorder with the exception of one variant, and that was soon dropped in an interim revision.

Once deviant, now desirable

“Definitely a change in culture affects diagnoses,” Leiblum says. “We used to think oral-genital sex was deviant and we have embraced that. Masturbation was evidence of out-of-control behavior, now we see it as not only normative but to be encouraged.”

So if enough people start to do it, or are more public about doing it, does that mean it is no longer a disorder? “I think it probably affects the degree to which people are willing to look at scientific evidence,” Regier says.

This fuzziness is why, starting in the 1980s, the field moved toward adding the notion of “distress” to the DSM.

“We do not consider something a disorder unless there is a clearly defined description of this entity and there is clearly some significant dysfunction and distress associated with it,” explains Regier. “I would say also if there is no victim involved … this behavior is not imposing a person’s will on another person, that is a critical component when one looks at conditions in this area.”

If you aren’t distressed, and everyone is a consenting grown-up, then there probably isn’t a disorder. But things won’t be that simple for the creators of the new DSM.

“How do you make a criteria that does not pathologize low desire?” Leiblum asks rhetorically. You add the need to be distressed about it. “But then whose distress should be looked at?” she asks, referring to a sexual partner. “You can have hypertension and not feel any distress because there is objective criteria for what is high blood pressure. But there is none of that for sexual diagnoses, even premature ejaculation. What constitutes premature?”

(At a press conference Monday, the International Society of Sexual Medicine made a stab at a definition, saying premature ejaculation is "a male sexual dysfunction characterized by ejaculation which always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about one minute of vaginal penetration; and, inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations; and, negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy.”)

This problematic lack of clarity, Leiblum argues, is especially acute for the paraphilias. Does the criteria amount to “If it’s mine it’s OK, but if it’s yours it’s kinky? These issues need to be grappled with.”