When NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander sets down in the Martian arctic on Sunday, it will open a new, icy frontier for scientists back on Earth.

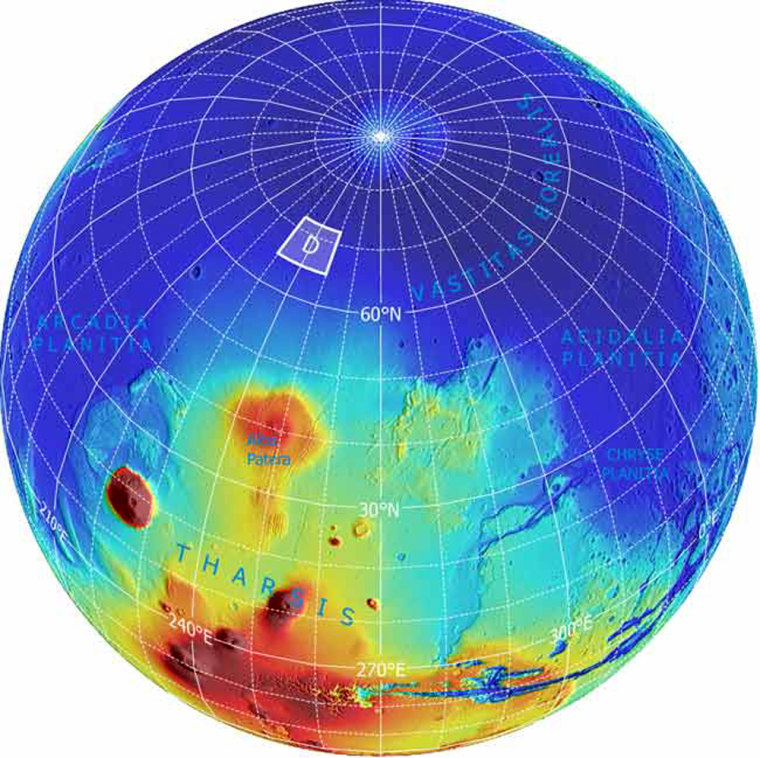

Phoenix, a stationary lander set to make a planned May 25 descent to the Martian surface, is going to where no probe has gone before — the northern plains of Vastitas Borealis on Mars.

"Ten years ago, you wouldn't have chosen this spot at all because it looks just like every other part of Mars," said Phoenix principal investigator Peter Smith of the University of Arizona. "A lot of the features aren't even named up there."

But it's the promise of what lies beneath the frozen surface features, signs of untouched Martian water ice first spotted by orbiters in 2002, which spurred NASA engineers and researchers to launch the $420 million Phoenix last August.

Wielding its robotic arm like a backhoe, Phoenix is designed to dig down in to the Martian soil to collect water ice samples. It will feed them into small onboard ovens and beakers to determine if its landing site may have once been habitable for microbial life.

"We believe that the ice is somewhere between 4 and 6 centimeters (1.5 to 2.3 inches) below the surface," Phoenix deputy principal investigator Deborah Bass of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory told Space.com. "It's not going to be ice skating rink-pure, white, shiny ice. It's going to be permafrost - dust, dirt and ice all mixed together."

Only one NASA spacecraft — the ill-fated Mars Polar Lander — has ever targeted a polar region of Mars for study, but that spacecraft crashed just before landing near the planet's south pole in December 1999. NASA's past successful Mars landers, the two Viking probes of the 1970s and '80s, and the hardy Spirit and Opportunity rovers that still explore the Martian surface today, set down near the planet's equatorial regions.

The history of Earth's own climate change and the building blocks of life are preserved in the ices near the Arctic Sea, Smith said during a Thursday mission briefing at the Pasadena, Calif.-based JPL.

"We're wondering if this is true on Mars," he added.

Phoenix's second choice

Phoenix's targeted landing zone lies within an ellipse about 50 miles (80 km) long and 12.4 miles (20 km) wide, with the bull's eye sitting in a broad, shallow valley some 800 feet (250 meters) deep.

It's rather chilly, with the average temperature expected to range between minus 110 to 28 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 73 to minus 33 Celsius) during Phoenix's primary six-month mission. The probe is landing during the late Martian spring at its target site to take advantage of long, sunlit days for its solar arrays.

But the landing site, known as Region D, was not the Phoenix mission team's first choice. It was selected only after high-resolution images from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spotted fields of large boulders that could topple Phoenix during landing in 2006.

"It had to be safe, there had to be ice," Smith told Space.com of the landing site selection. "We wanted some sort of surfaces features that showed there was ice so we weren't just going by other measurements, and those are the polygons that we see, which are the same as you see in the Arctic and Antarctic [on Earth]."

Polygons are crack features created by changes in subsurface ice, he added. Phoenix's Region D has those features in spades.

"What we see is a mottled terrain, caused by ice expanding and contracting underneath the soil, and it shapes the surface," Smith said Thursday.

Of key interest is whether the Martian soil will contain leftover salts from evaporated liquid water, which Mars researchers have long held as a basic ingredient for life, in the relatively recent past, Smith said. The Spirit and Opportunity rovers have found solid evidence that liquid water once soaked regions of the Martian equator in the ancient past, he added.

But evidence of recent liquid water near the Martian north pole, he added, would be boon for researchers studying the planet's water history, as well as for future missions designed specifically to seek out signs of life.

"We are going in blind into the northern plains," Smith said. "So are just looking for evidence that it was habitable."

NASA's will broadcast the Phoenix Mars Lander's Red Planet arrival live on NASA TV, with the next mission briefing set for 3:00 p.m. EDT (1900 GMT) on Saturday, May 24.