Just days before the planned delivery of the international space station's largest laboratory, its crew is facing a much more down-to-Earth problem: a stopped-up toilet.

This is no laughing matter. The outpost's long-term hygiene and routine comfort are now threatened, unless critical spare parts can be identified, found and loaded aboard the space shuttle Discovery as it sits on the launch pad in Florida.

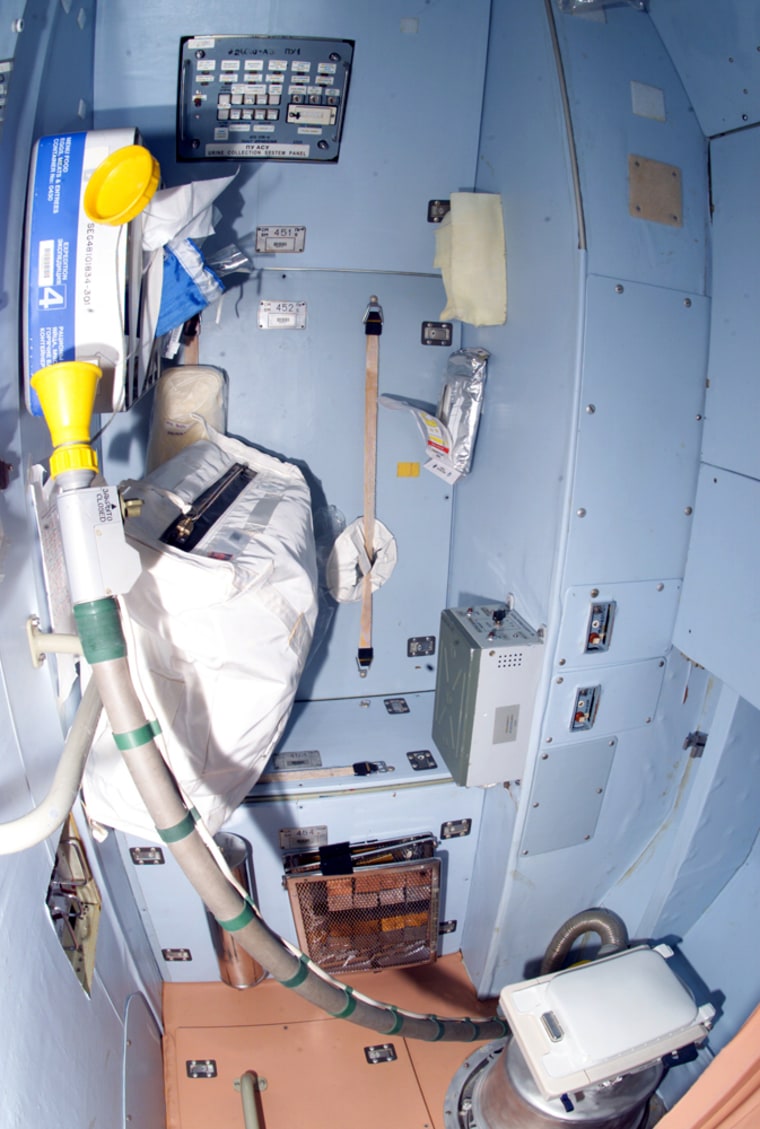

Long a subject of bathroom humor, these high-tech commodes must use fan-driven air flow instead of gravity to transport human waste away from a crew member’s body and into a sanitary receptacle. Early spaceflights didn’t even have this method, but relied on bags with sticky openings — and an emergency supply of such bags is indeed aboard the space station.

The current round of trouble started last Wednesday in the Russian-built Zvezda service module, the station's main living room, as noted in a NASA status report: "While using the toilet system in the Service Module, the crew heard a loud noise and the fan stopped working. After some troubleshooting the crew reported that the air/water separator was not working.”

Cosmonauts Sergey Volkov and Oleg Kononenko, assisted by NASA astronaut Garrett Reismann, tackled the problem immediately. They replaced the separator with a spare unit, but told controllers that the toilet didn't provide suction. Then they replaced the toilet's filter, which proved to be just a fleeting fix.

Mission Control in Moscow told the crew to turn off the toilet and use the unit inside their Soyuz transport ship. Designed only to support free flight between Earth and space and back, that unit has only enough storage capacity for a few days of crew use.

Over the next few days, the toilet was reported "fixed," and NASA's daily reports contained messages of "routine maintenance" on the unit. But rumors circulated within the space community that the fixes kept breaking.

On Tuesday, NASA spokesman Josh Byerly confirmed that the toilet was still balky.

“Over the weekend the crew experienced more trouble with space station toilet,” he told reporters. “They had thought they had corrected it but the same fault returned, and they fixed it again.”

The toilet didn't stay fixed for long. “It failed again this morning,” he concluded.

Byerly did not address other reports, passed along privately to msnbc.com, that a "fabrication flaw" has been discovered in the toilet's compressor units. One source in Houston said that the hardware used there for crew training may be flown to Florida for launch aboard Discovery, even though it too is expected to fail quickly. The source was not authorized to discuss the situation publicly, and thus spoke on condition of anonymity.

A major new unit, intended to allow the expansion of crew size from three to six members, is being prepared for launch late this year. Until then, the current hardware — and the supply of "Apollo bags" for fecal collection — may have to suffice. And if previous experience is any guide, the Russian engineers and cosmonauts will find McGyver-type solutions to make it work.

Over the years, the station's Russian-made life support hardware (such as oxygen generators and carbon dioxide scrubbers) has limped along, occasionally breaking down and then being fixed or replaced with spares.

Designed to be robust, and to be easily serviced in orbit, this hardware approach has shown resilience and “repairability.” That may be just the approach required for the life support systems to be used on years-long human missions to other planets.