It’s been said that necessity is the mother of invention. But if that lean lady is baby mama to our creative ambitions, then surely the daddy of invention is that unforgiving bastard named Deadline.

You know him: He’s the guy forever hovering over your shoulder shouting, “Hurry up! You haven’t got much time!” And while Father Deadline is a fantastic pain in the rump, without him breathing down our necks most of us human beings would never get around to inventing anything.

Just ask Petri Purho. The 24-year-old video game developer from Helsinki knows a thing or two about deadlines and inventions. Back in September of 2006, he gave himself a whopper of a deadline — he vowed he would create a new game every month for at least a year and that he would take no more than seven days to make each one.

It seems deadlines — even the self-imposed ones — work like a charm. Earlier this week, Purho unveiled his 21st game — the colorful and delightfully addictive “Planet of the Jellies,” which is like “Space Invaders” meets “Bejeweled” and can be downloaded for free from his Web site.

“If I don't have a deadline, I usually just sit home watching telly or surfing pointless Web sites,” Purho says. “So, having committed myself to this silly monthly games project, I'm just mostly motivating myself.”

He’s not alone. Independent and hobbyist game developers around the world have discovered that forcing themselves to make games under insanely tight deadlines is a great way to get games made. More importantly, it’s a great way to make some innovative, unusual and even some downright awesome games.

Meanwhile, three of the winning games from this year’s Independent Games Festival got their start under the deadline gun. Purho’s much-lauded game “Crayon Physics Deluxe” won the IGF grand prize and is based on a game he made in five days. Indie gaming hit “Audiosurf” won the Audience and Excellence in Audio awards and got its start as part of developer Dylan Fitterer’s seven-day game prototyping project. And “World of Goo” — winner of the Design Innovation and Technical Excellence awards — started out as “Tower of Goo,” a little game made in four days as part of the Experimental Gameplay Project.

The EGP got its start back in 2005 when four grad students at Carnegie Melon University decided they were fed up with the state of mainstream gaming.

Fed up with mainstream gaming

“We were bored with all the big budget games with all the crazy technology that couldn’t run on our computers,” says Kyle Gabler, one of the founders. “They were huge and overly complicated but they weren’t fun in the same way they were fun when we were kids. And we were like, ‘hey games don’t have to be complicated to be fun.’”

So Gabler and his cohorts set out to make as many simple-yet-fun games as they could in one semester, requiring each game be made in a week’s time and by one person only. By the time the semester was over, they’d made more than 50 games, many of them in only four days.

Granted, these weren’t exactly fully fleshed out video games as much as they were prototypes — bite-sized bits of fun that could be played for short periods of time while showcasing new styles of gameplay, not to mention the developer’s creative talents. The project piqued the interest of game industry executives. After all, it begged the question: How did four students make so many new, imaginative games in such a short period of time?

'You can't be afraid of failure'

Though he helped write a lengthy paper on the topic at Gamasutra.com, Gabler boils it all down to one key answer: “You can’t be afraid of failure.”

Just take a look at the big gaming companies where giant development teams have been known to spend many years and many millions of dollars working on a single game that, in the end, exhibits all the creativity of a paint-by-numbers picture.

“If you’re making just one thing — one game — you become terrified to take risks,” Gabler says. “But if you make 100 games, it’s okay if some of them fail.”

These days, the EGP is no longer a four-man operation. Any developer who wants to make a game under the project’s tight parameters is welcome to publish their creation to the project’s Web site, where anyone can play the game for free and offer feedback. Peruse the games here and you’ll find a veritable carnival of fascinating and oddball offerings. There’s “Gravity Head,” a game in which you use the character’s gravity-powered head to grow and deliver flowers, and “On a Rainy Day,” a game in which you grow a tree made out of hands.

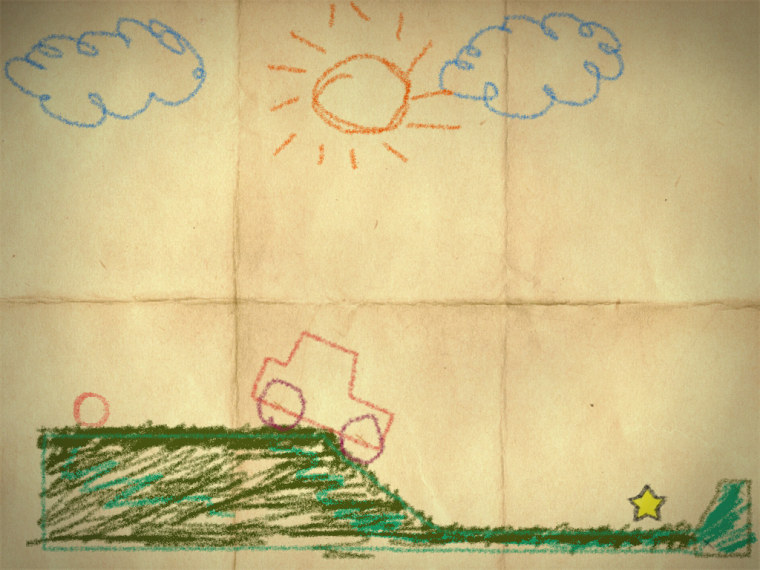

You’ll also find “Crayon Physics” posted there, the prototype to Purho’s award-winning “Crayon Physics Deluxe.” Though the goal of this puzzle game is simple — move a ball until it touches a star — the gameplay is wonderfully imaginative. Using your mouse, you draw various shapes, lines and objects in crayon on the screen. These objects (and the laws of physics) then nudge the ball where it needs to go.

Purho says it was the EGP that inspired him to challenge himself to make a game every month.

“It’s great for testing new ideas,” he says. “If the game turns out to be a turd, I've only wasted seven days on it. If, on the other hand, I had spent years making that game I would have to be sure that it’s a good game and thus probably wouldn’t go for the new, wacky, unproven ideas.”

At the Blue Moon Pub in Toronto on Friday, organizers will put together a makeshift arcade so that the public can play the games created during this year’s event. In addition to the time restriction, teams at this year’s jam also were asked to develop games that fit a specific theme: cheese. And just to spice things up, participants also were asked to include an image of a goat standing on a pole.

And so visitors to the TOJam Arcade will have a chance to play the likes of “Happy Goat Lucky,” a game that asks players to milk chunks of cheese from the head of a goat, and “Seas of Cheese,” a game in which players use the “Rock Band” drum controller to control a mouse who bludgeons his enemies with a fish drunk on oxygen. (I swear I’m not making this up.)

Yes, games made on the fly are often quirky and sometimes downright bizarre little inventions. Oh yeah, and on occasion they’re awful too.

With risk comes reward

But with risk there’s also reward. Just ask Dylan Fitterer, creator of “Audiosurf” – a game that literally allows you to ride the songs in your own music collection. The game has earned rave reviews from critics and a top-selling spot on Valve’s Steam download service. And Fitterer says it all started as a seven-day prototype called “Tune Racer.”

“If you keep your time budget really short, then the expectation of awesomeness is lifted,” Fitterer says. “You’re free to fail and when you’re free to fail you can try things that aren’t obviously good, and that’s when you end up with something new. You find the spark of something and you keep rolling with it.”

Winda Benedetti is a Seattle-based writer who would never write anything if it weren’t for deadlines. Tune in weekly to her Citizen Gamer column for a look at independent and casual games, as well as games that are flying under the radar but shouldn’t be.