“I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry,” wrote psychiatrist Frederic Wertham in his 1954 book, “Seduction of the Innocent,” which linked comics to the rise in juvenile delinquency.

Video-game fans hear this kind of outrageous hyperbole all the time, levied by critics, politicians, and other self-appointed guardians of morality. But sixty years ago, comic books were in the crosshairs. Back then, comics were the most popular form of entertainment in America. Between 50 and 100 million of the things were sold each week, mostly to kids and teenagers.

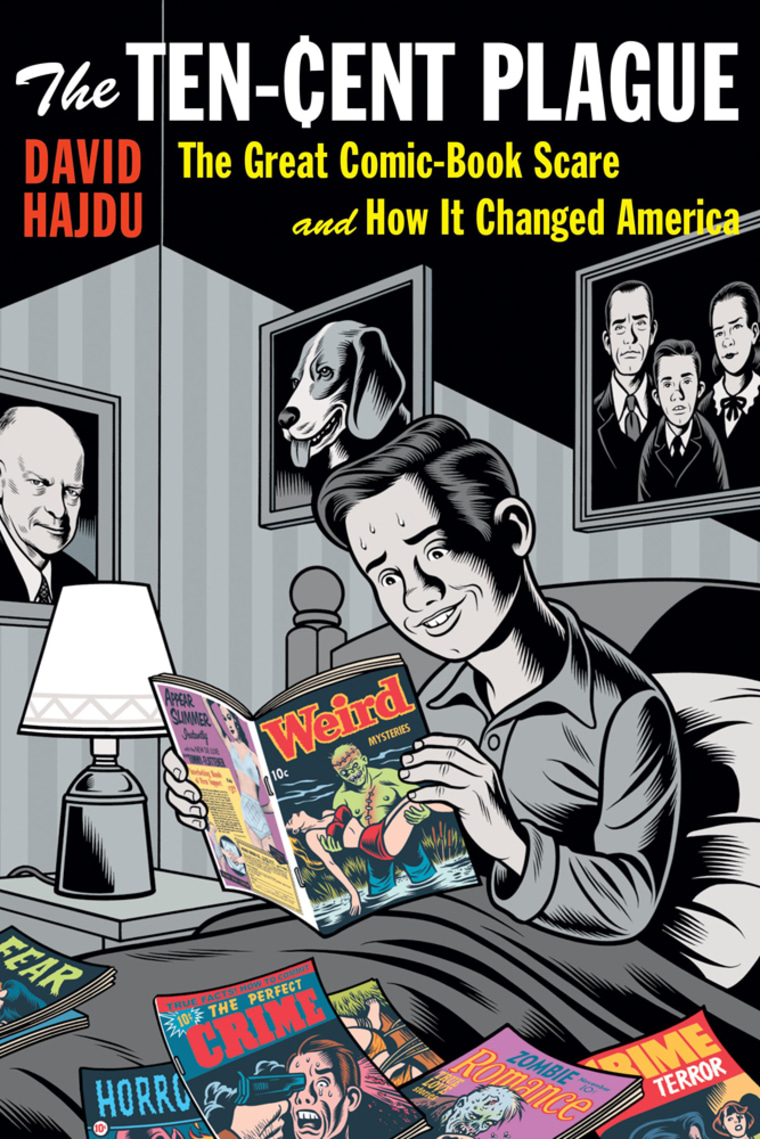

The stories in these books, says David Hajdu, author of the new book, “The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How it Changed America,” were unlike anything kids had seen before. They told tales of superheroes, but also of murder, crime and illicit romance. The illustrations could be shocking, and sometimes, the good guys didn’t win.

So, sixty years ago, grown-ups got nervous, articles were written, legislation enacted, Congressional hearings held. Sound familiar?

I spoke to Hajdu — who is also a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and a critic for The New Republic — about the rise and fall of comics, and how their unwelcome reception compares to today’s criticism of violent video games.

In our conversation, excerpted below, we discussed violence in art, the importance of diversity to the success of the comic-book industry and the function of culture “to kick parents in the ass.”

You write in your book that much of the rantings behind comic books were because, for the first time, a generation of young people were developing their own interests and tastes, along with, as you put it, a determination to indulge them. For many people, mysef included, it’s hard to imagine an America where teenagers weren’t characterized by their overt individuality — and in fact, celebrated and courted because of it. What was so different about that time and why didn’t a youth culture exist?

The interesting thing about comics, and why comics were early to be a source of economic and social power for young people was because they were affordable. I mention this in the book, but these were things that were made by young people, for young people, marketed directly to young people and priced for young people. And they’re the only work of expression, of art, that qualified as such. Kids could buy candy bars … but not much else, for a dime. There were no other forms of art or creative expression within their reach.

What would you compare (comics) to? Would you compare it to TV? Would you compare it to movies … to video games? Or was the phenomenon even bigger than all those things?

Comics and the late,’40s and ’50s were more popular than any form of popular entertainment. The way to fully absorb the power that comics had was to understand not just the reach, which was extraordinary, which was huge, but also that the content of those comics and the point of view of those comics and the sensibility of those comics was so radically different from that of anything else that young people can see. If kids are going to the movies, they’re not seeing anything like this in the movies. Movies were geared toward families. There was nothing like this.

Because of the purchasing power?

Right. It was purchasing power, partly, and the fact that young people were creating comics for other young people — and the fact that they’re doing so in the absence of much oversight or restriction. So, they were free to portray violence in a much more graphic way, and in a much more lurid way. They were free to portray the grotesque in a much more extreme way. You couldn’t be a 9-year-old and go to a movie and find the kind of defiant and transgressive behavior — and gleefully so — anywhere else.

You write in your book that the switch from the superhero-type comic to the darker forms of comics were what focused a lot of negative attention on them. Critics began to attribute what they saw as a rising tide of juvenile delinquency directly to comic books. Was that at all a fair characterization?

If I believed that comic books were benign and inconsequential and had no effect on their readers, then there’d be no point in writing about them.

Does the presence of violence in comics — like the presence of violence in any other form of popular entertainment — does it influence somehow the reader or observer of the work? Of course. We process art … we want to make it our own, we want to make it a part of us – of course it influences us. But in what way does violence influence us? There is no one simple answer and you can’t answer it in strictly good and bad terms.

I believe strongly that there’s a positive value in confronting the horrors of violence. To a significant degree the influence is positive. The Bible is full of violence, horrific violence. I’m not just rationalizing it, or justifying it, because I have a lot of problems with violence. But the various dimensions of this coexist and I feel very strongly that we have to confront all aspects of the influence of violence on the reader of a comic or the viewer of a film or the player of a video game.

That said, if we grant that art … has an influence on the readers, the influence, by necessity, cannot only be positive. It can’t, because that defies the complexity of human nature … and also the vagaries of human nature.

You have three kids, and I’ve heard you say that you’re concerned about the participatory nature of video games. Is that where the line is?

I haven’t done the serious scientific work to know if something different happens when you’re doing the clicks and that means pulling the trigger and doing the shooting. I suspect that something different happens, because I feel something different when I’m playing the games. There’s not the same kind of detachment and distance. And that’s my own personal response. I think the participatory dimension makes video games different, but that’s only a supposition or an inference.

Do you allow your children to play games?

I try to establish a strong sense of right and wrong and ethical values in the house, and then let the kids make their own decisions…we’re not big on prohibitions in our house. I think there’s a real danger in that. You’re creating allure of the forbidden … and you’re contributing to the romantic allure.

Is there a lesson there for parents — that every generation has a form of entertainment that the adults just don’t get?

(Entertainment exists) to alienate parents and to challenge the value system of parents. The new is always shocking, and (then) the new becomes acceptable. This is just the pattern that repeats itself over and over in the culture. It applies not just to violence and horror but to tonality in music and sexuality in film and literature — it plays in different ways socially and aesthetically. That’s the function of entertainment for young people — to kick parents in the ass. So, in that way, to the degree that that’s the case, horror and crime comics did their job.

Parents, politicians, religious leaders have gone after virtually every art form associated with youth culture – comic books, rock music, and now, video games. And with comic books, these efforts eventually had a chilling effect (on the industry). How is it that current “objectionable” entertainment products avoided that same fate?

The question is, why did comic books lose that battle? The main reason that comic books lost is that their advocates didn’t have much voice. The advocates were kids and no one was listening. Nobody cared what they thought.

Another reason is simply economic. The big corporations weren’t publishing comics.

You write that the comic book industry was comprised of outsiders: ethnic minorities, women, people who were disadvantaged financially and perhaps couldn’t gain entry to prestigious schools or professions. How important was that diversity to the success of the medium?

It was immeasurably important because comics of all kinds — even superhero comics — were explicit, overt, opulent in their portrayal of the pride of (their) outsider status. Superman was the ultimate immigrant. He was an immigrant from another planet.

It’s essential. I think it’s the main thing that comics were here to say, was that outsiders of every sort were not lesser for their outsider status. That had, in one way or another, something over the orthodoxy.