It’s not just Americans who are wondering how the battle between John McCain and Barack Obama will come out on Election Day.

People from Uganda to Pakistan have written to me asking questions about the election.

Someone in Strabane, Northern Ireland recently asked:

If you live long enough in the United States — for at least 14 years — and have a political background, can you run for president and vice president?

Let’s assume our reader is referring to a citizen of a foreign country who immigrates to the United States from South Korea, the United Kingdom, or some other country.

The answer is no.

That person cannot serve as president, even if he or she becomes a naturalized United States citizen and meets the other qualifications for president, such as being at least 35 years old.

Article II of the Constitution, which lists the qualifications, says a person must be “a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution.”

A foreigner who becomes a naturalized U.S. citizen can serve as a member of Congress, or as a state governor, but cannot serve as president.

There’s some legal debate about what the phrase “natural born Citizen” means. For instance, what if an American woman was on a weeklong Italian vacation and gave birth? Could that baby someday be president of the United States?

This legal question has never been definitively resolved.

One thing that is clear, however, is that the Framers of the Constitution didn't intend for foreigners who emigrated to the United States to become president.

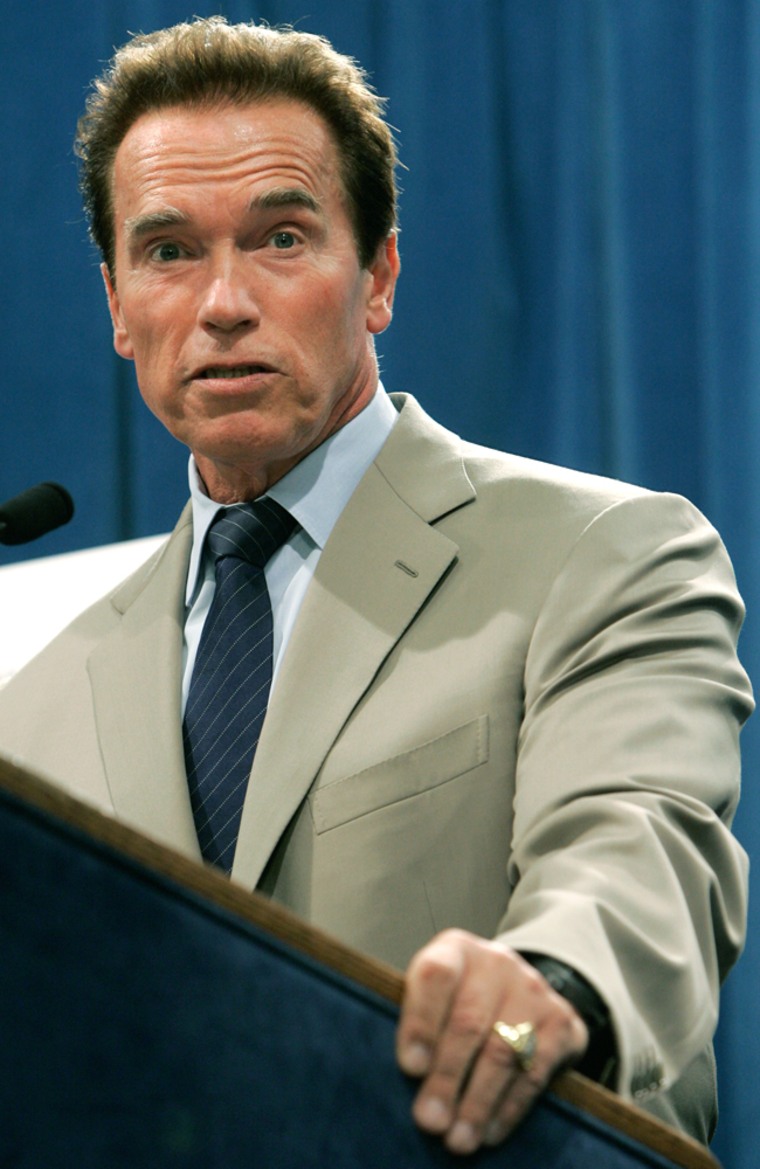

And this includes naturalized U.S. citizens such as Austrian-born California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who was born in Prague in what is now the Czech Republic.

The authoritative commentator on the the Constitution, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, explained in 1833 that this provision of the Constitution “cuts off all chances for ambitious foreigners, who might otherwise be intriguing for the office; and interposes a barrier against those corrupt interferences of foreign governments in executive elections, which have inflicted the most serious evils upon the elective monarchies of Europe.”

In 2003, Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, proposed an amendment to the Constitution that would make naturalized citizens eligible to be president, but that amendment hasn’t come to vote in Congress.

Persons born in the United States — other than children of enemy aliens or foreign diplomats — are automatically given American citizenship.

So it’s possible that a baby born on U.S. soil to a foreign woman who had entered the United States illegally could someday grow up to be president of the United States.

A reader from Uganda asked...

Does American politics call for international observers like other countries all over the world?Nothing in U.S. law requires election observers to be invited to watch balloting in presidential elections. But in 2004 and again this year the U.S. State Department has invited observers from the Organization for the Security and Cooperation in Europe, or OSCE, to witness the balloting.

In 2004, the OSCE sent 92 monitors from several nations, including Norway, Canada, and Kazakhstan, to observe the presidential election.

Here are other questions we've fielded — on everything from campaign contributions to the makeup of the Electoral College:

I was born in Puerto Rico but have been in the U.S. Army for the last 18 years and decided to change my home state to the state of Florida. Am I able to vote for a president in the upcoming election?According to the Florida Secretary of State’s office the answer is: Yes, you can vote in the Nov. 4 presidential election, assuming you register in time. In Florida, the deadline for registration in order to vote in the presidential election is Oct. 6.

Puerto Ricans living in Puerto Rico cannot vote in the presidential election because the Constitution says that only the citizens of states and the District of Columbia have the right to vote in those contests.

However, Puerto Ricans are United States citizens, and Puerto Ricans who move to Florida, or any other state, and establish legal residency can vote in presidential elections.

But professor Christina Duffy Burnett of Columbia University Law School points to Romeu v. Cohen, a 2001 decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

The court ruled that Americans who move from the United States to Puerto Rico and establish residency on the island cannot vote in presidential elections.

The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Voting Act (UOCAVA) of 1986 protects the voting rights of U.S. citizens residing in foreign countries.

Even though residents of Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories are American citizens, they are not covered under UOCAVA.

So a New Yorker moving to Paris or Shanghai can vote in a presidential election, but a New Yorker moving to Mayaguez, Puerto Rico cannot.

UOCAVA also applies to members of the military on active duty, whether they're stationed in the United States or overseas.

The soldier at Fort Stewart must first register to vote by filling out a voter registration form. Since he's in the military and is covered by UOCAVA, he can register using the Federal Post Card Application.

The Overseas Vote Foundation has an excellent, user-friendly website. It can walk soldiers and other service members through the steps they need to take in order register and vote.

The Federal Voting Assistance Program also has useful information on how to make ensure that Americans in uniform can vote.

What is the difference between public and private campaign moneyPrivate money is raised from campaign donors. There is not limit to the total amount that an individual candidate can raise, but private donors are limited to giving $2,300 for the primary season and another $2,300 for the general election.

Public money comes from the voluntary check-off system on individual income tax returns. The individual tax check-off amount is $3.

A candidate can opt in or out of public financing during the primary season. It's the same for the general election. For example, in 2004, Democratic contender John Kerry didn't use public money during the primary season, but he did during the general election.

During the primaries, if a presidential hopeful decides to accept public funding, every dollar raised from donors is matched with money from the public fund.

But primary candidates who choose to use the public system must agree to an overall spending limit, as well as spending caps in each state.

For the 2008 primary season, the overall limit was about $50 million.

But it's a different story during the general election. There's not matching program, it's just a flat amount determined by the Federal Election Commission.

The FEC has set this year's general election fund at $84 million.

Why would a candidate chose not to use public funding?When a candidate accepts public funding, they're limiting the amount of campaign cash they can spend.

For example, as of June 20, Obama’s campaign had raised more than $287 million. And there's every reason to think he'll continue to raise more and have that money to spend.

If he chose to use the public system, he'd only have $84 million to spend.

John McCain on the other hand, is accepting public funds for the general election. This could mean he feared being outpaced by Obama if he was also singularly reliant on private donors.

In the general election, Obama is the first presidential candidate to opt out of the public financing system since it was first used in the 1976 election.

So why was the public financing system created?In the aftermath of the Watergate scandal and some related campaign funding scandals, Congress created the system out of concern that "big money" donors had become too powerful.

But in a campaign such as Obama’s which has raised nearly $300 million, a single donor who makes the maximum contribution of $4,600 is a minuscule drop in a huge bucket.

Are there ways around this system?Maybe not around the system, but through it.

Both candidates are able to help raise money for their respective national party committees. In turn, the Republican National Committee and the Democratic National Committee can return the favor.

Each national party committee can spend up to $19 million in coordination with their presidential candidate. They can also spearhead voter mobilization efforts and advertising campaigns.

Donors can also give the RNC and DNC up to $28,500 a year — much more money than can be donated to an individual candidate.

At what point are presidential candidates required to stop spending primary monies and start spending from their general election coffers? Generally speaking, the party’s conventions are the dividing line between the primary season and the general election.

But in effect, both McCain and Obama have been campaigning for the general election ever since they clinched their parties’ nominations.

For McCain that date was Feb. 7 when Mitt Romney dropped out of the GOP contest; for Obama it was June 7 when Clinton called it quits.

For a candidate, like Obama, who is operating outside the public financing system, there’s really not much distinction between spending money on winning primaries and spending money to win the general election.

He can spend as much as he wants any time he wants.

There’s an unresolved dispute between the Federal Election Commission and the McCain campaign as to whether he did opt out of the public funding system in the primaries.

His campaign said he was opting out; the FEC has not yet ruled on whether McCain has followed the correct procedure for opting out.

Here's the rest of our question and answer series:

Why can't we have a one-day presidential primary election? Why must it span over months and yet we only have one day to vote in the general presidential election?

Well, dear reader, you may think a national primary is a good idea. Now all you need to do is persuade the 7,382 members of all 50 state legislatures.

So, here's the answer to your question: There’s no federal law which decides that there will be a national primary on a given date. Arguably such a law would be unconstitutional since the Constitution leaves most electoral matters to the state governments.

Each state legislature makes its own decision about when the state’s primary will be held.

The national committees of each major political party also have a big voice in deciding the schedule: look at the heated argument this year over Michigan and Florida deciding to jump ahead of the calendar mandated by the Democratic National Committee.

The National Association of Secretaries of State, which represents the officials who oversee elections in each state, has called the current primary system "seemingly arbitrary and chaotic."

The NASS has proposed a plan to divide the country into four geographic regions and have regional primaries in March, April, May and June. The order of the regions would rotate every four years. But the plan would allow Iowa and New Hampshire to keep their preferred place in the calendar.

The NASS is trying to persuade the two major parties to adopt the plan and then use their leverage to get the states to concur.

The parties would penalize states that went outside the plan by not seating their Democratic and Republican delegates at the respective party conventions.

Given the number of state legislatures and the other urgent matters that legislators must contend with, it seems a difficult task for the NASS to succeed in its plan.

In the category of questions from genuinely puzzled readers, we’ve received several recently from people wondering about vice presidents.

When does the presidential nominee have to choose a vice presidential candidate by?A vice presidential candidate must be chosen by the time the party’s national convention opens, or at least by the day the convention officially nominates its ticket.

After all, the purpose of the convention is to officially nominate presidential and vice presidential candidates.

By tradition, the announcement is usually made shortly before the convention, although in 1980 Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan picked George H.W. Bush on the second day of the convention, after a tentative deal with former president Gerald Ford to serve as Reagan’s running mate fell apart.

How does the winner decide his/her running mate? Can they choose the runner-up to be the vice presidential candidate?The winner often decides to pick someone who can bring strength to the ticket in a part of the country that the presidential nominee is not from.

For example, in 1988, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, the Democratic presidential nominee, picked Sen. Lloyd Bentsen of Texas as his running mate. In 1932, Gov. Franklin Roosevelt of New York chose House Speaker John Nance Garner of Texas as his running mate. The Roosevelt-Garner ticket carried Texas; the Dukakis-Bentsen ticket did not.

Sometimes a running mate is picked for ideological balance, or because they have the reputation of being an experienced Washington operator (Dick Cheney in 2000 comes to mind).

When and why did the vice-president stop being the person who came in second in the electoral vote count?

In the first four presidential elections, starting in 1789, no distinction was made between electors’ ballots for president and vice president. The person getting the most votes was president; the person with the second highest number of votes was chosen vice president.

But with the development of political parties (not anticipated by the Framers of the Constitution) this led in 1796 to Federalist John Adams being elected president and his rival, Republican Thomas Jefferson being elected vice president.

Jefferson actively opposed Adams — which made for an unhappy presidency.

In 1800 there was confusion when an electoral vote tie occurred.

The Twelfth Amendment, ratified in 1804, tried to clarify the process: electors would now cast separate ballots for president and for vice president. With the dominance of a two-party system, electors more and more tended to be party loyalists and voted for the president and vice presidential candidates their party had nominated.

What is a national party convention? It is a quadrennial event during which the party formally nominates its presidential and vice presidential candidates.

Do delegates to national conventions perform any substantive function? They cast their votes for the person they want to be their party’s presidential nominee. But usually, party’s choice for nominee has been decided by the time the delegates get to the convention.

The delegates end up ratifying a choice that has already been made by the voters. They also serve as colorful backdrop for the candidate’s acceptance speech and do a lot of socializing in the convention's host city.

When was the last time there was a national convention at which the outcome was in any doubt? There has not been a convention at which the nominee was in any doubt since the Republican Convention in 1976 in Kansas City, where it looked like Ronald Reagan might be able to take the nomination from President Gerald Ford.

During the Democratic presidential nominating contest, we heard an awful lot about the so-called superdelegates. Who or what are they?The category includes Democratic governors and members of Congress, former presidents and former vice presidents, retired congressional leaders, and all Democratic National Committee members, some of whom are appointed by party chairman Howard Dean.

They are not elected to be delegates by voters in a primary or caucus. Instead they are delegates ex officio by virtue of the office they hold, or by virtue of being members of the Democratic National Committee.

The Democratic Party created the superdelegate system in the 1980s to give the party’s elected officials more of a voice in choosing the presidential nominee.

Do superdelegates have extraordinary powers or privileges which regular delegates do not possess? No, they don’t. They have one vote at the convention just like the other delegates.

Has a presidential nominee ever had to step down after being nominated by his party? No.

Has a vice presidential nominee ever had to step down after being nominated by his or her party? Yes. In 1972, Sen. Thomas Eagleton of Missouri was the Democratic vice presidential candidate chosen by presidential nominee Sen. George McGovern. Less than two weeks after the Democratic convention, news reports revealed that Eagleton had been hospitalized for exhaustion and depression in the 1960s and had undergone psychiatric care and electroshock treatments.

At first, McGovern announced his support for Eagleton to remain on the ticket but he soon stepped aside.

McGovern and the Democratic National Committee then chose R. Sargent Shriver, former Peace Corps head and brother-in-law of Sen. Edward Kennedy.

On Nov. 4, will Americans be voting for presidential candidates or for electors? Voters will be casting their ballots on Nov. 4, 2008 for a slate of electors in each state and the District of Columbia. Those electors, in turn, will cast votes on Dec. 15, 2008 for the candidates to whom they are pledged.

For instance, on the California ballot, there will be a slate of 55 Democratic electors pledged to the Democratic presidential candidate and a slate of 55 Republican electors pledged to the Republican candidate.

A voter will chose one slate or the other (or perhaps the slate of a third party such as the Green Party).

How many electoral votes does it take to win the presidency? 270.

How many electors are there?538

How are the 538 electors divided among the 50 states?They are divided roughly on the basis of population. States with large populations, like California and Texas, get lots of electors; states with small populations, like North Dakota and Vermont, get few.

No matter how small its population, each gets at least three electoral votes.

Each state gets a number of electors equal to the number of its members of the House of Representatives (which is proportional to population), plus two — since every state has two senators.

Tennessee, for example, has nine representatives and two senators, therefore it has 11 electoral votes.

If a state has many illegal immigrants living in it, will it get more representatives in the House, and thus more electoral votes than it would otherwise have? Yes.

All people, citizens and non-citizens, legal residents and illegal residents, are included in the Census count used to determine state population and representation.

But illegal immigrants may avoid contact with Census enumerators and therefore may be undercounted.

Is the allocation of presidential electors among the states perfectly proportional to each state’s population? No.

Wyoming, with a voting age population of about 370,000, has three electors. California, with a voting age population of 24.4 million, 66 times bigger than Wyoming’s, has 55 electors, which is only 18 times as many electors as Wyoming has.

This bonus for small states was one of the compromises made at the constitutional convention in 1787 in order to persuade the states with smaller populations to join the Union.

If a majority of a state’s voters in the Nov. 4 general election vote for the Republican ticket, then the Republican slate of electors is chosen. At that point, the Democratic slate of electors does not matter.

Will the voters in each state know who the electors are? In some states, the electors’ names appear on the Nov. 4 ballot along with the presidential candidates’ names. In other states, the electors' names do not appear on the ballot.

Who selects the electors? The political parties choose the electors. They are often party loyalists selected as a reward for years of faithful service. They may be elected officials or persons who have personal ties to the presidential candidate.

In 2004, for example, one of the Democratic electors in New Hampshire was former Gov. Jeanne Shaheen, whose husband Bill had run Democratic nominee John Kerry’s primary campaign in that state.

What was the intention of the Framers of the Constitution when it came to the role of electors?The intent was that "electors would be free agents, to exercise an independent and nonpartisan judgment as to the men best qualified for the Nation's highest offices,'' Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson wrote in 1952.

But the system has evolved into something quite different from what the Framers intended: electors today almost always act as rubber stamps, chosen by their party to vote for its nominee.

What does the Constitution say about choosing electors? Article Two says, "Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors" equal to the number of senators and representatives to which the state is entitled in the Congress.

Is it up to each state’s legislature to decide how electors are chosen? Yes. A legislature could for instance, appoint a specific group of electors, such as retired judges, or it could choose electors randomly from a list of the state’s registered voters, or it could say the presidential candidate who wins the most votes nationwide would get all of that state’s electoral votes.

The Constitution does not require that electors be chosen to reflect the popular vote in that state, although the tradition of following the popular vote is well established.

What is the Electoral College? It is the name applied collectively to all 538 electors.

The term "Electoral College" does not appear in the Constitution but was written into federal law in 1845, and appears in the United States Code (3 U.S.C. section 4), as "college of electors."

Does the Electoral College convene, like a college faculty would gather for a meeting? No, the Constitution requires each state’s electors to convene in the state capitol, but the electors from all 50 states and the District of Columbia never all meet in one place at the same time.

Why don’t all 538 electors meet in one place at the same time? The Framers of the Constitution feared that, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, if the electors all met in one place, they would be vulnerable to "cabal, intrigue and corruption" and that foreign governments who sought "to gain an improper ascendant in our councils" might bribe them.

Also, Hamilton warned, electors would be more prone to "heats and ferments, which might be communicated from them to the people" if they met in one place.

Regardless of whether a candidate wins 51 percent of the votes in a state, or, in a multi-candidate race, say, 35 percent of the votes in a state, why does he or she get 100 percent of that state’s electoral votes? Forty-eight states have laws that mandate a winner-take-all system for electoral votes: The person with the statewide plurality of the votes gets all the electoral votes.

What does "plurality" mean? In this context, it means "more votes than anybody else who ran."

In an election in which there are more than two choices (as there usually are if you include Libertarian and other minor-party candidates), a plurality is the number of votes cast for the winning choice, even if that number is less than 50 percent.

Most electoral laws for national, state and local elections in the United States say the winner is the candidate who gets the plurality.

A few states require a majority in some elections: for instance in Louisiana, elections for governor, attorney general and other state offices have an all-inclusive primary as round one of its voting. If no candidate gets a majority in that first round, then the top two vote-getters, no matter which party they belong to, proceed to a final round.

Which states do not use the winner-take-all system? Maine and Nebraska. In those two states, one elector is awarded to the candidate receiving the most votes in each of the congressional districts, and the remaining two electoral votes are awarded to whoever gets the most votes statewide.

How is a majority different from a plurality? A majority is a number more than half of the total votes cast.

So how does a plurality vote work in presidential races? A few examples will make it clear: In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon, competing with two other major candidates, Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace, won only 38 percent of the vote in Tennessee, but he got all of Tennessee’s electoral votes.

In 1992, Bill Clinton, competing with two other major candidates, Ross Perot and George H.W. Bush won only 40 percent of the vote in Colorado, but he got all of its electoral votes.

But doesn’t this mean that the majority of voters in Colorado in 1992 – 60 percent of them – didn’t want Clinton to be president? Yes, it does mean that. But it also doesn’t matter legally. The plurality system is the one that has evolved: pluralities win, not always majorities.

Are there moves afoot to change the electoral vote system? Maryland and New Jersey have enacted a measure called the National Popular Vote bill.

Under this law, a state's electoral votes would be awarded to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The Maryland legislation would not take effect until the enactment of identical laws in enough other states to reach a majority of the electoral votes, that is, 270 out of 538.

But smaller states such as Vermont, South Dakota, and Alaska would lose clout under this proposal. The Electoral College system guarantees that every state, no matter how small its population, gets at least three electoral votes.

Could Congress scrap the electoral vote system? It could begin to do so by proposing an amendment to the Constitution, but that proposal would need to be ratified by three-quarters of the states.

Has Congress ever considered scrapping the Electoral College system? Yes, in 1969 the House approved a proposed constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College and to provide for direct popular election of the president.

That plan called for a minimum of 40 percent of the popular vote required to win the presidency or a runoff election between the top-two finishers should the minimum not be met.

The proposal was killed in the Senate by legislators from small states and Southern states.

If the electoral vote system appears to be undemocratic, what arguments do supporters of the electoral vote system use to defend it? Republican presidential contender Ron Paul argued in 2004 that the Founding Fathers "created the electoral college to guard against majority tyranny in federal elections. The president was to be elected by the 50 states rather than the American people directly, to ensure that less populated states had a voice in national elections."

He added, "Not surprisingly, calls to abolish the Electoral College system are heard most loudly among left elites concentrated largely on the two coasts. Liberals favor a very strong centralized federal government...The Electoral College system threatens liberals because it allows states to elect the president, and in many states the majority of voters still believe in limited government and the Constitution."

Why does the District of Columbia, which is not a state and has no voting representatives in Congress, get three electoral votes? Because Congress and the requisite number of state legislatures decided in 1961 to amend the Constitution to give D.C. residents the right to vote in presidential elections, but not in congressional elections.

A constitutional amendment rather than a mere statute was needed to do this because Article II of the Constitution specifically refers to states choosing presidential electors.

A House report, in explaining this constitutional amendment, said D.C. residents "have all the obligations of citizenship, including the payment of Federal taxes, of local taxes, and service in our Armed Forces. They have fought and died in every U.S. war since the District was founded."

The amendment would remove the "anomaly of imposing all the obligations of citizenship without the most fundamental of its privileges."

Has the District of Columbia always cast the majority of its votes for the Democratic candidate for president? Yes. No Republican has ever come close to winning in D.C. The best showing by a Republican was by Richard Nixon who got 22 percent of the vote in 1972.

Is it possible for a candidate to win the nationwide popular vote and yet lose the electoral vote? Yes, he can do so by amassing big vote margins in states in which his party is dominant, while losing other states narrowly.

It happened in 2000 when Al Gore won California with a margin of victory of nearly 1.3 million votes. Gore won New York with 1.7 million votes to spare.

But Gore lost New Hampshire by only 7,211 and lost the electoral vote, 271 to 266. He also lost Florida by 537, but many Democrats thought a recount would have shown him winning that state.

No. A candidate who wins 80 percent of the popular vote would have won many states by wide margins. Thus he or she would get all the electoral votes from most states, well more than enough electoral votes to give him or her more than the 270 needed.

The biggest percentage winner of the nationwide popular vote in any election since 1900 was Democrat Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Johnson won 61 percent of the votes cast. This gave him enough votes to win 45 out of 50 states, and 486 electoral votes.

Once they are chosen, what do each state’s electors do? On Dec. 15, in each state’s capitol, the state’s electors will meet to cast separate ballots for president and for vice president.

Can an elector pledged to vote for a candidate cast his or her vote for someone else?Yes. But this rarely happens.

Since the first election in 1789, ten electors have decided to vote for a presidential candidate other than the one to whom they were pledged.

In 1948, for example, Tennessee elector Preston Parks was pledged to the Democratic candidate, Harry Truman, but instead cast his vote for States’ Rights presidential candidate Strom Thurmond. It didn’t affect the outcome of the election, as Truman won with 303 electoral votes.

Can an elector be punished if he does not vote for the candidate to whom he or she is pledged? In some cases he or she could be: 25 states and the District of Columbia have laws binding electors.

In some states the penalty for electors who do not vote for the candidate to whom they are pledged is severe: in North Carolina for example, an elector who breaks his or her pledge can be fined $10,000.

Who counts the electoral votes to determine who in fact won the presidency?Congress will meet in joint session on Jan. 6, 2009 to count the votes of the electors.

If at least one member of the House and one member of the Senate object to any electoral votes from a state, then the House and Senate each go into separate sessions to debate and vote on the contested electoral votes. Both the House and the Senate must vote to reject the challenged electoral votes in order for them to be rejected.

In theory, there could be such an outcome.

The current system which is set forth in the 12th Amendment to the Constitution would have allowed for electors to choose, for example in the 2000 election, Al Gore for president and George W. Bush for vice president.

But the two major political parties choose tickets of president and vice presidential candidates and the electors (who are loyal party members) almost always do what the party expects and vote for the entire ticket.

What happens if the electoral vote ends up in a 269-269 tie, or in a multi-candidate field, if no candidate gets 270 electoral votes? The Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution says that if no candidate gets a majority of the electors then the House of Representatives shall choose a president from among the top three vote-getters.

What procedure would the House use to go about choosing a president in this situation? In these circumstances, each state’s delegation in the House has one vote. So, for example, California’s 53 members of the House would caucus and vote as a bloc. Since there are more Democratic House members from California than Republican members, California’s one vote would go to the Democratic presidential candidate.

How many times has the House of Representatives chosen a president? Twice, in 1801, when it chose Thomas Jefferson, and 1825, when it chose John Quincy Adams.

The 1968 election came close to being thrown into the House when Nixon received 301 electoral votes, Humphrey 191 and Wallace 46.

Had there been a shift of three percent of the vote in Illinois and four percent in Tennessee, Nixon would have lost both those states and would have wound up with 264 electoral votes, six short of the number required.

What would happen if a state, due to litigation and ballot disputes, can’t finish its vote count and therefore can’t choose its electors by the date on which electors are supposed to meet?It is likely that the legislature of that state would appoint a slate of electors, rather than allowing the state to lose the opportunity to have some voice in the election.

Can citizens in U.S. Territories, such as Puerto Rico and American Samoa, vote for president? No. Article II of the Constitution only refers to electors who are chosen by the states, although the 23rd amendment, ratified in 1961, does provide for electors chosen by the District of Columbia.

Because the major political parties have decided under their own rules to give Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and other U.S. territories some role in the presidential nominating process. Federal law regulates the primaries only to a limited extent; most decisions are left to the political parties.

Seven states allow voters to register on Election Day: Idaho, New Hampshire, Maine, Minnesota, Montana, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

In how many states are voters required to present a government-issued photo ID before they can cast their ballot? According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 24 states ask voters to show identification prior to voting. Seven of these states specify that voters must show a photo ID.

But "all states have some sort of recourse for voters without identification to cast a vote," such as a provisional ballot, according to the NCSL.

Yes, you can, assuming that you register to vote by the deadline set by your state and assuming that you meet the qualifications for voting.

They vary somewhat from state to state, but basically you must be at least 18 years old, a citizen of the United States, and a resident of the state in which you are voting.

In Florida, to take one example, you must also not have been judged to be mentally incapacitated with respect to voting. You must also not have been convicted of a felony in Florida, or any other state, without your civil rights having been restored.

In Florida, you must also sign an oath swearing that you "will protect and defend the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of Florida."

In a few states, such as Virginia, once he gets out of jail a convicted felon must obtain a pardon or a restoration of citizenship from the governor in order to vote. But in many states the felon’s voting rights are automatically restored once he finishes serving his sentence.

Yes, you can.

The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act, enacted in 1986, sets up procedures for you to vote using an absentee ballot. Your state of residence for voting purposes is the state where you last lived prior to going overseas. See the for more information.

Is voting in presidential elections regulated by the states or by the federal government? Voting in presidential elections is regulated by both the states and federal law.

For example, states can set different rules for where to vote, for recounts, and whether to allow voting by mail.

But Congress has imposed some mandates. For example, the 26th amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1971, required that 18 year olds be permitted to vote in every state. And the 1975 expansion of the Voting Rights Act requires bilingual ballots in places where there are minorities who do not speak English.

In how many places in the United States are bilingual ballots mandated by federal law? There are 371 counties and other jurisdictions in 30 states which are mandated to provide bilingual ballots. The languages covered include Spanish, Vietnamese, Navajo and Chinese.

No, this has never happened.

The closest this has come to happening was on Feb. 13, 1933, when former bricklayer and transient Guiseppe Zangara fired shots at President-elect Franklin Roosevelt just after he finished giving a speech in Miami.

Zangara missed Roosevelt, but one of his shots hit Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak who subsequently died from his wounds. Zangara was convicted of murder and executed on March 20, 1933.

But what would happen if a president-elect were to die after the general election on Nov. 4, but before the electors cast their ballots on Dec. 15?

According to "After the People Vote: A Guide to the Electoral College" published by the American Enterprise Institute, if the president-elect died, the national committee of the president-elect’s political party would meet and choose a new nominee, and thus a new president-elect.

The electors, when they meet in the various state capitals on Dec. 15, are free to choose whomever they want, but in all likelihood would go along with the choice made by the national party committee.

If the president-elect died after Congress met on Jan. 6, 2009 to count the votes of the electors, then the vice president-elect would become president on Inauguration Day, Jan. 20.

What is a primary and what is caucus? How do they differ? In a primary, voters simply cast their ballots and then go on with the rest of their day.

But a caucus in more participatory, with supporters showing up in person at designated sites throughout the state, such as a high school gymnasium, and standing up to be counted for their candidate.

In Iowa caucuses, there’s debate and jockeying among those who show up, as supporters of one candidate try to woo the undecided caucus participants.

How are a caucus and a primary alike? In both, voters are ultimately choosing delegates to their party’s national convention, the body that formally nominates their presidential candidate.

Why do some states have primary elections and other states have presidential caucuses? State legislatures and state parties determine which form of balloting they prefer. In some states such as New Hampshire, the primary has become well entrenched and legislators are not likely to switch to a different system.

Can independent voters take part in a political party’s primary? It depends on state law. In New Hampshire, for example, independent voters can go the polling place on primary day and ask for the ballot of the Republican Party or the Democratic Party. Then, once they cast their ballot, they can fill out a form and switch back to being independent.

California used a similar system in its Feb. 5, 2008, presidential primary.

Why do Iowa and New Hampshire get to vote first and not states with larger populations, such as California? The short answer is tradition and inertia.

The preferred place of Iowa and New Hampshire is cemented by tradition, by party rules and by the difficulty of getting the state legislatures and political parties to agree on how to alter the process. While Iowa and New Hampshire have traditionally cast the first votes, Democrats in 2008 added Nevada and South Carolina to their early schedule in an attempt to add more variety to their electorate. The Republicans also had an early primary in South Carolina.

How and when did the Iowa caucuses become important? Iowa’s prominence dates to Jimmy Carter’s effort there in 1976. As the campaign started, Carter was a little-known former one-term Georgia governor, a pygmy in a field that included heavyweights such as Sen. Henry Jackson, the Democrats’ pre-eminent national security expert.

But in the Iowa caucuses, an event in which just 38,500 people took part (and which Jackson chose to bypass), Carter won 28 percent of the vote, finishing second to "uncommitted," which was the preference of 37 percent of the Democrats who took part.

How does the Iowa Republican contest differ from the Democratic caucuses? The Iowa Republican Party conducts a straw vote of those attending the caucuses.

Democratic caucus-goers form different groups, with each of the contenders needing to have at least 15 percent of the attendees at each precinct caucus in order to get any delegates from that precinct.

How many people take part in the Iowa caucuses? In 2008, more than 227,000 people took part in the Democratic caucuses, up sharply from 122,000 in 2004.

Among Republicans, there were around 120,000 caucus-goers, up from 86,000 in 2000, the last time there was a competitive Republican contest in Iowa.

How many people vote in the New Hampshire primary? More than 230,000 people voted in the Republican primary on Jan. 8, 2008, while more than 280,000 voted in the Democratic primary.

How has New Hampshire proven to be decisive in past elections? Since 1920, New Hampshire has been the first state in the nation to conduct a presidential primary. Its importance dates back to 1952 when Dwight Eisenhower beat Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio to win the New Hampshire primary, putting Ike on track to securing the Republican nomination.

On the Democratic side, too, New Hampshire has a history of making or breaking candidacies. For instance, Granite State voters essentially drove President Lyndon Johnson out of the race in 1968 by giving him a disappointing 49 percent and giving insurgent Sen. Eugene McCarthy 41 percent. Pundits deemed this a victory for McCarthy.