Dozens of scared children filed silently into the bare room, their eyes on the cracks in the floor.

One by one, in low voices, they told of being tortured by the Kenyan army because they were suspected of aiding rebels. They told of being beaten and made to shake hands with corpses. They told of being forced to crawl through barbed wire tunnels and of genitals squeezed by pliers.

Then the children took off their shirts. White scars crisscrossed the dark skin on their backs like grains of rice. Some were still bleeding.

These children are among hundreds in western Kenya who have been terrorized, many twice over, first by a militia in their villages and then by the army sent to fight it. The militia forced children as young as 10 to become soldiers. In a widespread crackdown, the army then rounded up the children and thousands of adults and tortured them, human rights groups say.

The Associated Press interviewed some of the children in a detention center, brought in by a human rights advocate without the knowledge of government officials or the military. The children have been held since April on charges of promoting warlike activities. Their identities and location are withheld to protect them from reprisals.

Army sweeps up men, boys

In March, the Kenyan government sent its army to crack down on the Sabaot Land Defense Force militia, which is named after the Sabaot region. But instead of hunting down militia fighters where they hide in the forests of Mount Elgon, the army swept up thousands of men and boys from the surrounding villages.

Since then, so many reports of murder and torture have emerged that Kenya's state-run human rights commission is calling for the prosecution of the defense minister and top army and police officials. There are also calls for the United States and Britain to suspend millions of dollars in aid and training to the Kenyan army.

The U.S. has asked for $7.45 million for "peace and security" purposes for Kenya in 2009. Britain is providing more than $1.96 million this year to fight terrorism and has allocated $7.83 million for regional security initiatives based in Kenya.

Representatives of both governments in Kenya told The Associated Press they are deeply concerned over the reports of abuses and are calling on the Kenyan government to investigate. But the Kenyan government says the army has received no complaints.

The militia in Mount Elgon formed because of land conflicts, the same issue that fueled violence in Kenya after disputed elections in December. Squatters who had farmed the same fields since they were children were evicted in a government land scheme, and the rich grabbed plots set aside for the landless.

Militia flourishes in Mount Elgon

The militia flourished in the thick forests of Mount Elgon, where 166,000 people live in poor villages next to a dormant volcano. Some families encouraged children to join in the hope of securing land in the 370-square-mile district. Others were given a stark choice: pay the militia up to 50,000 Kenyan shillings or $830 — far beyond the reach of most — donate their son, or die.

One 15-year-old joined last year to protect his family after the militia killed his uncle.

"They shot him in front of me," the boy said. "He was begging for his life on his knees."

He spent two months in the forests and learned to shoot alongside eight other children. He saw a boy forced to kill his own father. He fled with a 10-year-old when the militia began producing victims for reluctant recruits to kill.

Some children simply disappeared. One 17-year-old girl was abducted by four men armed with machetes on her way back from school. Her father dared go to their forest hideout and ask after his missing daughter, who sang in the school choir and dreamed of being a doctor.

"They threatened to slaughter me if I took it further," he said, his voice suddenly raw. "I could not protect her."

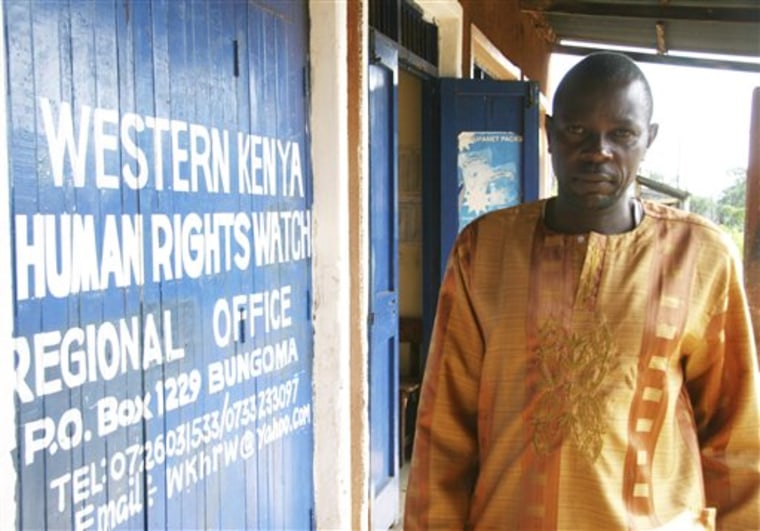

Her name joined a growing list of missing children in the battered notebook of Job Bwonya of the local Western Kenya Human Rights Watch.

The first kidnapping he recorded was of 17-year-old Joshua, seized in July 2006. When word spread that he was recording cases of disappeared children, 24 families rushed forward. But four weeks later, Joshua's parents, brother and 9-year-old sister were gunned down in the family's cornfield, and the flow of families reporting missing children slowed to a trickle.

So far Bwonya has recorded 42 cases of missing children likely seized by the militia, and has heard of many more. A partial survey of schools a year and a half ago found 650 children had disappeared. Grim newspaper clippings plaster the plywood walls of his windowless office, and anguished testimonies about murders spill from bulging files.

"Families are terrified to talk," he said. "No one can protect them."

Now Bwonya has another worn book with a new set of cases of missing children, this time ones who villagers report were taken by the Kenyan army. He said testimonies from those released by the military indicate at least 22 children have been tortured to death. Bwonya himself fled the country for a couple of weeks after the military came looking for him.

No comment from military

The military in Mount Elgon does not talk to reporters. But Bogita Ongeri, a spokesman for the defense department in Nairobi, denied all allegations of torturing children. He said the army has combed its ranks since claims of torture surfaced but has not found a single soldier guilty of misconduct. The army had treated more than 7,000 people for injuries, he added, but their injuries came at the hands of villagers who spontaneously attacked them as militia suspects.

"No military personnel has been involved in torture," he said. "We do not have any juveniles in military detention centers. They have not been there."

But the children interviewed by the AP said soldiers plucked them out of school or from the streets, tortured them and caged them for days without food or water. Some had to help load dead people onto helicopters that flew out in the direction of the forest and returned empty.

Martin Wanyonyi, another human rights advocate, has records of 70 children in detention, including some whose names were confirmed by the distraught parents of the missing. Wanyonyi said a recent visit to Bungoma prison revealed dozens of tortured children among the 1,400 inmates crammed into cells designed for 400. Some were as young as 11. The stench of sewage permeated the prison, he said, and moans and screams filled the blackness.

He also showed the AP records that documented the injuries of four boys tortured so badly that prison authorities refused to accept them, insisting they be sent to a hospital instead.

Land issues remain

In the meantime, Kenya's land issues remain unresolved. And the powerful politicians that villagers and former fighters say lead the militia remain free.

"The conflict in Mount Elgon is but the worst example of the poisonous relationship between Kenyan politics, land grievances and violence," said Ben Rawlence of New York-based Human Rights Watch.

If the children are released, some can trace their families. Others have no parents left after murders by either the militia or the military.

Peace and justice are far beyond the hopes of most families. Mothers say their ears still strain beyond the drumbeat of rain on a tin roof or wind rustling through cornstalks for the sounds of a vanished child's voice.

Some scarred children will eventually limp home along the winding mountain trails. Others never will.