If the presidential election were decided by speeches alone, it would be over already.

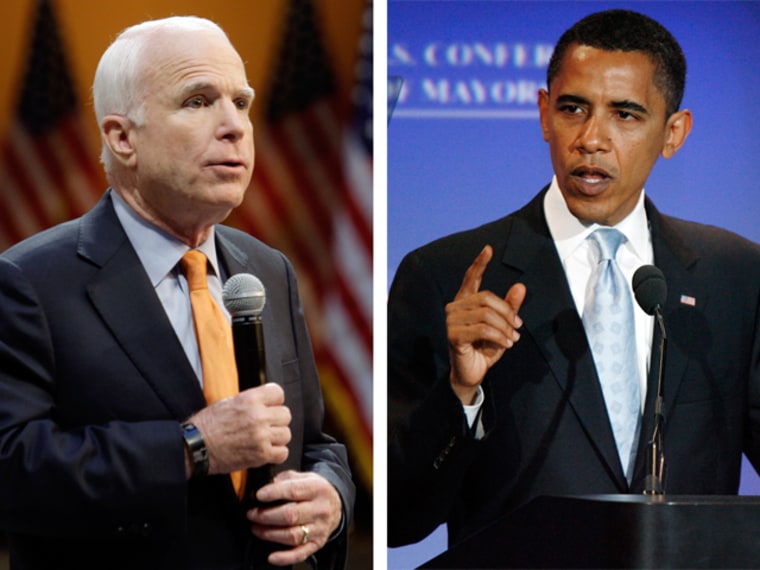

Barack Obama soars, John McCain struggles. Obama beams, McCain grins at the wrong time.

Obama looks off into a heavenly distance and then right at YOU.

McCain pivots his head in three positions — left, center, right, center, left, center, right. He may be speaking to "my friends" but he is looking, quite obviously, at a projected script.

Both use a teleprompter, but you can only tell with one of them.

When McCain is on stage making a big speech, you can imagine yourself in his shoes, as if you're in a panicky dream that traps you some place you don't belong, with all those eyes on you.

His discomfort makes him authentic and that's one reason it's not game over.

Words, expressions and gestures

After eight years of the sentence-mangling George W. Bush, eight years of the windy Bill Clinton, four years of the squeaky George H.W. Bush, it's been some time since Americans have had a compelling orator in the White House or even running for the job.

McCain shares certain qualities with candidates of the past. Like Al Gore, he can be clunky on the stage; funny, charming and sharp-witted up closer, and able to give an informed opinion — like it not — on any topic, off the top of his head.

Gore, of course, lost. But the oratorically unadorned war hero Dwight Eisenhower prevailed over opponents of lyrical prose and resonant voice. So did the plain-spoken, flat-voiced Harry Truman, whom no one ever accused of eloquence.

Like Hillary Rodham Clinton in the Democratic primaries, McCain acknowledges Obama's superior ability to grip a crowd. He counters the same way Clinton did — by saying they are words, just pretty words.

What makes Obama, who is set to speak Thursday at Berlin's Victory Column, so good at the scripted speech? Why might that be a mixed blessing? And what to make of McCain's stilted delivery?

Some thoughts from specialists in political rhetoric:

Wayne Fields, director of American culture studies at Washington University in St. Louis and author of "Union of Words: A History of Presidential Eloquence."

"It's this compelling mixture of something fresh and at the same time something we recognize from our own past," Fields says of Obama's style. "It has a kind of Old Testament call to the people."

The rise and fall of Obama's voice, the judicious repetition and the seamless interplay between words, expressions and gestures can keep people captivated longer than normal for a political speech.

"You give him more time to develop an idea," Fields said. "There's a kind of beauty both to the thought and to the expression of that thought that we take a kind of pleasure in. It is not painful to listen to those speeches. ... There's something that makes us unaware."

All to Obama's benefit?

Not necessarily.

"We're afraid we might be seduced," Fields said. "We don't trust ourselves or leaders when it comes to language. We're sort of suspicious of eloquence, yet at the same time we desire it."

As for McCain, he said, what you hear is what you get.

"You got to dance with who brung you and this is who he is," Fields said. "If he tries to sound like somebody else, then the central appeal that he's brought into his election will be lost, will be compromised.

McCain's style conveys, "I'm not saying anything fancy. There's nothing here that's very difficult. It's just the way I am."

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania and author of 15 books on politics, including "unSpun: Finding Facts in a World of Disinformation."

"Senator Obama's strength as an orator is his ability to deliver scripted texts in a way that expresses a sense of lived conviction," she says. "Audiences are unaware that he is delivering from a teleprompter. By contrast, the audience is painfully aware that Senator McCain is using a teleprompter."

Take away the script and the arena, substitute an uncontrolled exchange with voters close up, and it can be a different story.

"Senator Obama does not as readily or as convincingly express empathy in these environments as does Senator McCain. Senator Obama seems detached, analytic, and professorial at times. Senator McCain has a quick wit."

Jamieson puts Obama on par with Ronald Reagan in their delivery of formal speeches, and says his windups are something to behold.

"Senator Obama makes skillful use of history to argue that his candidacy marks a major moment for America. His perorations are masterful," she said, while McCain's are flat.

Passages that rivet crowds

Yet Obama's big speeches may not be fully successful.

"Some passages in Senator Obama's speeches draw attention to their rhetorical artistry," Jamieson contends. "They seem self-consciously crafted. The text of a speech should not draw attention to its means of persuasion."

She says both men make effective use of their personal story to heighten the audience's response.

"In one case, audiences know that they are hearing a person whose mother came from Kansas and father from Kenya. In Senator McCain's case — a former POW who behaved heroically under all but unimaginable circumstances."

Obama's declaration that America is not a nation of red states and blue states but of United States has raised goose bumps on Republicans as well as Democrats and demonstrates how repetitious words and passages can rivet a crowd.

It's one of his signature moments — introduced at the 2004 convention. His voice rises with the phrase and he lifts his hand as if holding a pencil or handing over a train ticket.

Similarly, but more aggressively, John Kennedy wagged his index finger at quickening intervals as he asserted in his 1961 inaugural address: "Ask NOT what your country can do for YOU, ask what YOU-CAN-DO-FOR-YOUR-COUNTRY."

Robin Lakoff, a linguistics professor at the University of California at Berkeley whose books include "The Language War," said Obama has tapped Kennedy's ability to be in tune with the times, even if his phrases are not yet for the history books.

He also reflects some of Reagan's skill at making a conversational connection.

"And he does it without anything dialectal," she added, noting Bill Clinton used his Southern accent to convey warmth.

"Obama speaks purely standard American English," said Lakoff, a Democrat. "Nevertheless, he has fashioned it into this warm, folksy kind of instrument."

Lakoff sees only limited use of black rhetorical traditions in Obama's speech — not the rhyming, rhythms, cadences or flamboyance associated with Jesse Jackson, the late attorney Johnnie Cochran ("If it doesn't fit, you must acquit") or the incomparable Martin Luther King Jr.

"He doesn't sound black unless he deliberately wants to, but that's very seldom."