As I was laboring over last week's column, I received a one-line e-mail from a respected journalist: "Can you please rail against the NYT for their 'neutral' fav/unfav offering?"

The issue he raised was immediately familiar, having to do with the unique way that the CBS/New York Times survey asks respondents to describe their opinion of public figures. It had reared its head that morning in a front-page poll story in the New York Times. Deep in the story, authors Adam Nagourney and Megan Thee noted that Barack Obama's wife, Michelle, "was viewed favorably by 58 percent of black voters, compared with 24 percent of white voters."

The Obama campaign immediately objected to that reference (among others), noting that Cindy McCain's favorable rating among white voters on the survey was just 20 percent. And even Nagourney later conceded that the story should have mentioned "that 72 percent either have no opinion about Mrs. Obama or hadn't heard enough about her, to avoid any suggestion that 80 percent had an unfavorable view of her."

With our attention about to turn to convention bounces and, as such, to how well voters know and rate each candidate, now is probably a good time to consider the questions that pollsters ask to gauge the popularity of public figures.

The favorable rating is probably as old as political surveys. The earliest poll question in the Roper Center iPoll Databank to use the word "favorable" was from a July 1939 Roper/Fortune survey, one of the earliest in the archive: "Have the impressions you have gotten of the King and Queen of England during their visit here, been favorable, unfavorable, or neutral toward them personally?"

Nearly 70 years later, pollsters continue to ask variants of that basic question, but then as now, subtle differences in the wording and answer choices can produce highly inconsistent results.

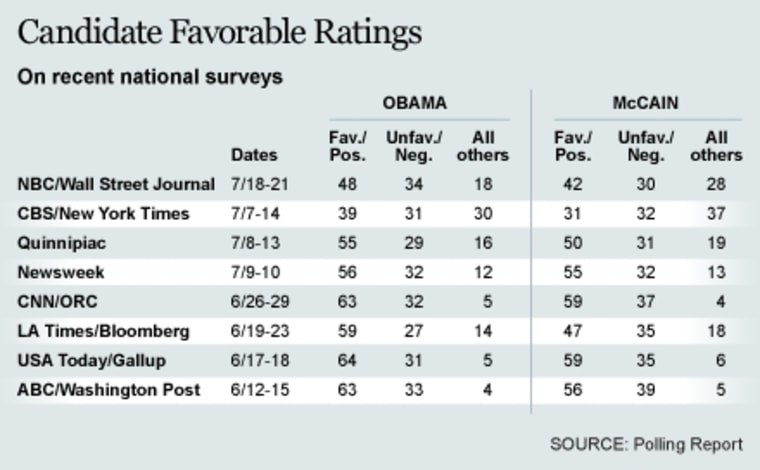

Let's consider the favorable ratings of John McCain and Barack Obama as measured on eight recent national surveys of registered voters. What is especially interesting is that the polls show relatively little variation in their "unfavorable" or "negative" ratings, but fairly large shifts from poll to poll between the "favorable" or "positive" category and the various "other" responses ("neutral," "undecided" or "unsure").

The most likely explanation for the difference is the way the pollsters ask their questions. First, consider the question asked by USA Today/Gallup and CNN/Opinion Research Corp.: "We'd like to get your overall opinion of some people in the news. As I read each name, please say if you have a favorable or unfavorable opinion of these people -- or if you have never heard of them." At that point they read each name and wait for an answer.

The Gallup and ORC questions push respondents to choose either "favorable" or "unfavorable." They include no explicit neutral category. They offer the "never heard of" option when introducing the question, but they do not provide interviewers with a specific probe that repeats the answer categories. Over the last month, this form of the question has produced the biggest "favorable" ratings and the smallest percentages that are neither favorable nor unfavorable.

Now consider the CBS/New York Times question: "Is your opinion of [NAME] favorable, not favorable, undecided, or haven't you heard enough about [NAME] yet to have an opinion?"

Unlike the favorable ratings used by Gallup and most other pollsters, CBS/NYT includes both an explicit neutral category ("undecided") and the option for respondents to say they don't yet know enough to have formed an opinion. CBS/NYT pollsters also repeat each answer category after reading each name.

So, not surprisingly, this poll finds more Americans in the categories other than favorable and unfavorable than other surveys do.

The other pollsters fall in between both in terms of their question format and their results. The NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, for example, offers an explicit "neutral" category, but ABC/Washington Post does not. Quinnipiac and Los Angeles Times/Bloomberg do not offer a neutral category, but do repeat the "haven't heard enough" option after each name.

All of this points to something important: Most registered voters -- and especially those who are uncertain about their choice -- recognize the names of the presidential candidates but know very little else about them, even at this stage in the campaign. Such a pattern is not unusual and tends to support the pattern of voter "ambivalence" my colleague Ronald Brownstein observed recently in a series of interviews with voters in Colorado. "The political commentariat," he wrote, "may be obsessively grading each thrust and parry in the nonstop jousting between the Obama and McCain campaigns, but virtually none of that dueling is reaching the voters I met."

The lower-than-average favorable ratings produced by the CBS/NYT poll may seem at odds with those on other surveys and are apparently a source of confusion even for experienced reporters, but they ultimately provide a more accurate measure of the true opinions of real voters. If "somewhat favorable" really means "I know the name but I'm not sure," we ought to call it that.