The White House grasp of developments in war-battered Georgia has been hampered by confusing reports from the ground and intelligence resources that initially were focused more on Iraq and Afghanistan than the former Soviet republic.

One-sided and possibly exaggerated accounts of actions from both sides and the Bush administration's difficulty in independently verifying information about the war have left the White House standing on an ever-changing platform from which to speak out on the crisis.

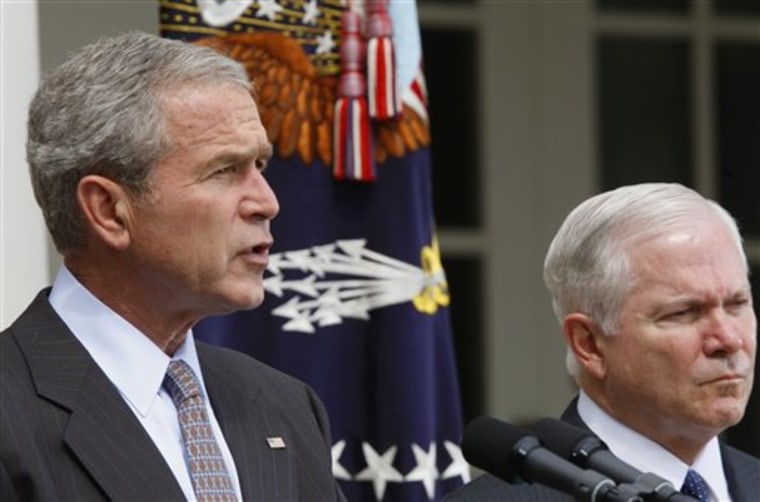

At least three times on Wednesday, President Bush referred to being concerned about "reports" that Russia had violated its pledge to a provisional cease-fire. White House press secretary Dana Perino hedged her answers to questions about the conflict, too.

"We do have credible reports that Russia has taken actions that violate the cease-fire agreement, and that's what the president was referring to," she said. "I can't get into specifics, but we do have those reports and we're concerned about them, and we are working to get concrete information. It's not the easiest thing in the world given the geography and the cutoff of information."

'Difficult to get accurate situational awareness'

Beyond intelligence reports and media accounts, State Department officials on the ground are relaying information through cables and phone calls, said Gordon Johndroe, a spokesman for the National Security Council. "It is very difficult to get accurate situational awareness in real time in a crisis that is fast-moving," Johndroe said. "This is a motorized conflict in a relatively small area and that means the situation on the ground can change very quickly."

Still, defense officials concede that in the early stages of Russia's move into Georgia over the weekend, the United States did not have a good view of the war, which has strained relations between Washington and Moscow.

The Defense Department has limited intelligence-gathering assets, including satellites, and defense officials said the bulk of the military's eyes and ears have been focused on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. During the weekend, as the situation in Georgia worsened, the Pentagon authorized the repositioning of some satellites to get a better understanding of what was happening on the ground.

While the military, as well as U.S. intelligence agencies, can collect imagery or audio at various times and locations, that information then has to be melded with other data and observations from people who are there. According to defense officials, intelligence early Wednesday was mixed and provided a somewhat ambiguous picture of whether Russian troops were launching attacks in Gori or other cities.

The officials, who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because of the sensitive nature of intelligence-gathering, said the quality of information improved throughout the day. By late afternoon, the United States had what officials called more robust intelligence on the movement of Russian forces around Gori.

Lack of policy and analysis'?'

Ariel Cohen, a research fellow in Russian and Eurasian studies at the Heritage Foundation who has visited Georgia about a half-dozen times, countered this explanation, saying it's "ludicrous" to assert that satellite capabilities are to blame for the administration's lack of information about the situation in Georgia. Cohen, who said he alerted the Bush administration to Russia's preparations for war in Georgia more than two years ago, said "glaring gaps" in research and analysis by the nation's national security team are to blame.

"I think this is a significant lack of policy and analysis" about events in the region, he said.

Stephen Flanagan, an analyst on security and defense policy and intelligence issues at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said the lack of international presence in either South Ossetia or Abkhazia — the two separatist regions that have been largely overrun by Russia since fighting broke out last week — is making it especially difficult to verify reports.

"I think the administration has most of what they need," he said. "I'm sure we have a lot more information than they're discussing publicly."

Two U.S. officials also denied that the United States is having any special problems or unusual difficulties with getting intelligence on this conflict, though they acknowledged that the situation is confusing. The United States is not involved in the conflict, initial reports often are incorrect in the fog of war and it's hard for people there who might give them information to get around the country to validate developments, they said.

In addition, the Russians often say one thing and the Georgians say another, and the international community must work to reconcile the two stories to learn the truth. Two U.S. officials also mentioned that the Georgians have been exaggerating in some of their reports about what the Russians are doing, further complicating the administration's effort to find the truth.