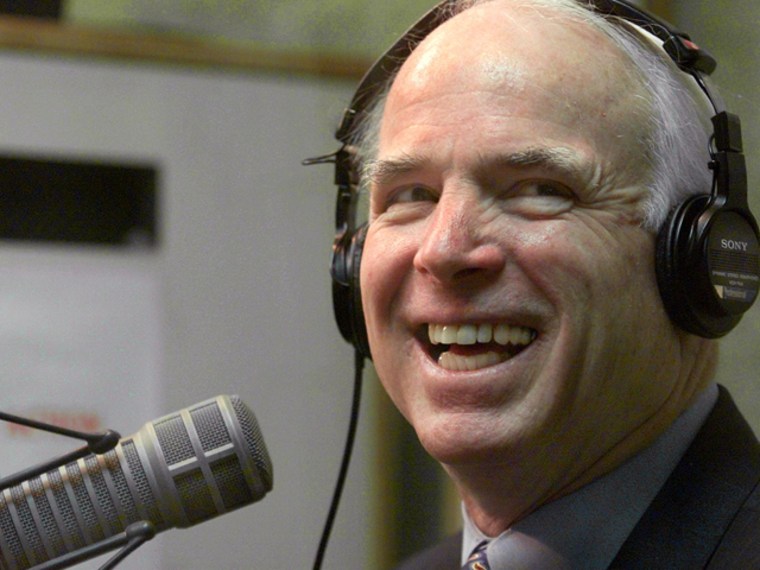

Senator John McCain’s Republican primary campaign looked all but hopeless. He had risked the wrath of his party to push for an immigration overhaul and now, just months before the Iowa caucuses, his grand compromise was falling apart on the Senate floor as well.

“Lindsey, my boy, this may bring us down,” Mr. McCain said, turning to his friend Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina. “But wasn’t it fun?”

By this spring, when Mr. McCain had astounded political handicappers by virtually locking up the nomination, the thrill of noble defeat had been replaced by an anxious discomfort about his own victory. “I refuse to believe that this is possible,” he said, curling up his face during an interview on his campaign plane. “I tend to be fatalistic about these things.”

As he accepts the Republican presidential nomination on Thursday night in St. Paul, John Sidney McCain III, of Arizona, stands at the pinnacle of a career defined by a singular ambivalence about his own ambition, and success. Time and again, he lunges for the prize, then lashes himself for letting his pursuit get the better of him — for doing favors for his patron Charles H. Keating Jr., for stooping to ugly attacks on George W. Bush during the 2000 primary, for outbursts of temper at lawmakers who get in his way.

It reflects what his brother, Joe McCain, calls a “public dialectic” between the senator’s drive to succeed and his desire to serve a higher cause. For decades his outward display of that inner conflict has proved advantageous, helping advance his career by forging his image as the un-politician, the candidate with an almost reckless disregard for his own fortunes.

His critics assert that the McCain of 2008 is not the McCain of 2000, or even 2007. He has surrounded himself with former protégés of Karl Rove, whose tactics he once denounced, embraced positions he once repudiated and initiated a series of attacks on Senator Barack Obama’s patriotism that some say resemble the rhetorical rough-housing he regretted eight years ago. “Bring Back the Real McCain!” the cover of The Economist magazine implored last week.

His loyalists, though, say such complaints hold Mr. McCain to the standard of a nostalgic mythology that grew up around his last campaign, overlooking the tough competitor that was there all along.

“He is same guy he has always been, wrestling with all the things he does trying to be the guy he believes he has to be,” said Mark Salter, Mr. McCain’s closest aide. “But we are not just going to say, ‘O.K., we’ll just lose — we will lose graciously — maybe everybody will remember him fondly.’ ”

It is his combination of lofty aspirations and hard jabs that has made him a political force.

“You can’t be above it all and accomplish all that he has accomplished,” said Bob Kerrey, a Democratic former Senate colleague of Mr. McCain and fellow Vietnam War veteran. “It’s a little like saying that Muhammad Ali was above boxing while he was doing the rope-a-dope. It’s a tactic. It’s not devious or anything. It is what it is.”

The Crowded Hour

Mr. McCain has always had contradictory impulses: he enjoys both boxing and bird watching, cites as favorite movies both “Viva Zapata!” and “A Fish Called Wanda,” and quotes his idols Henry Kissinger and Henny Youngman.

He wins admirers by boasting of the unpopularity of his views — on campaign finance reform, on the Iraq war, on immigration. An avid gambler, he is drawn to big bets and long odds — whether picking 1-against-99 fights with his fellow senators over their official perquisites, or defying convention by picking as his running mate a little-known Alaskan with a reputation as an irritant-reformer. He is the most disruptive figure in the Republican Party, and, as of Thursday night, its standard-bearer.

Until recently, Mr. McCain was one of the few United States senators who drove himself around Washington — tailgating, dashboard-pounding and cellphone-taking. “My philosophy is just to go like hell,” Mr. McCain once explained. “Full-bore.”

He often invokes “the crowded hour,” a term from his political hero, Theodore Roosevelt, referring to the assault on San Juan Hill. In the Roosevelt and McCain lexicon, the phrase equates to a moment of reckoning, when worthy men prove themselves.

Aboard his campaign plane in February, Mr. McCain caught his breath after the four months that transformed him from a principled loser to his party’s contender for the highest office in the land. “This has been a very crowded hour for me,” he said.

The Self Critic

Few politicians have apologized as profusely or as fortuitously as Mr. McCain. He may be the only candidate-author whose editor cut back on the self-criticism in the first draft of his campaign memoirs. “He was quite happy to lacerate himself,” recalled the editor, Jonathan Karp.

Joe McCain attributes his brother’s habit of public penitence to the example of their father, Adm. John S. McCain Jr. “He would whack us on the rear end with these leather slippers that he had,” Joe McCain recalled. “Then he would come back out rubbing his hands together, and I could tell he felt so bad that I almost felt sorry for the guy.”

Their father expected them to live up to a military code of honor and atone for any lapses, teaching them that it was the only way to retain the respect of those around them.

“I think one of John’s deepest needs is to be believed and trusted,” Joe McCain said. After submitting to a forced “confession” statement as a prisoner of war in Vietnam, John McCain has said, he found relief from his shame by provoking his guards to beat him.

John McCain’s aspirations were always grand. As a boy, he dreamed of an admiralty like his father’s. As the Navy’s liaison to the Senate, he set his sights on becoming a member. In Vietnam he had mused aloud to cellmates about becoming president, and as soon as he won his first Senate race in 1986 he “felt an emotional need to envision some future goal,” as he recalled in his 2002 memoir, “Worth the Fighting For.”

But he exasperated himself with his own self-defeating behavior — letting his barfly antics as a young pilot undercut his credibility as a Navy officer, or later jeopardizing his friendship with his patrons, Ronald and Nancy Reagan, by leaving his first wife for a glamorous beer heiress 20 years younger, Cindy McCain. “He has always felt very guilty about it,” his Navy colleague James McGovern recalled in an interview eight years ago. “I have never talked with him for more than 40 minutes when he didn’t bring it up.”

For most of his political career, Mr. McCain was a straight-ahead partisan. He voted along party lines, crushed his opponents by outspending them, and sought to run the Senate Republican Campaign Committee. His preferred public image — the straight-talking maverick — did not emerge until well after 1989, when he became one of five senators caught up in a scandal over meetings with savings and loan regulators on behalf of Mr. Keating, a wealthy donor. In a marathon news conference and nonstop media interviews, Mr. McCain became the foremost critic of his own poor judgment (any other accusations he called defamation).

“The national media was saying, ‘John McCain is the only one who is talking about this, and sometimes it seems like he won’t shut up,’ ” recalled Jay Smith, a political consultant who advised Mr. McCain at the time. As the senator kept talking, “the scandal seemed to improve markedly for him.” Seeing that his openness was effective, Mr. McCain later wrote, he adopted it as a permanent “public relations strategy.”

Repentance became a theme of his career. He wove his regret over decades of smoking Marlboros into his drive for a tobacco tax overhaul. Then he said he felt ashamed of his own party for neglecting children’s health by blocking the bill. He even organized his best-selling 1999 memoir, “Faith of My Fathers,” as a confession. Written with Mr. Salter, his longtime aide, as a springboard to the 2000 presidential race, it catalogs his decades of misbehavior leading to the realization in a Vietnamese prison of the deeper satisfaction of “a cause greater than myself.” Soon he was turning the Keating episode into a similar parable of short-sighted self-interest.

In the 2000 Republican primary, Mr. McCain sometimes seemed to be battling his own impulses as much as he was his rival, Mr. Bush. He opened the year with a speech in New Hampshire denouncing contemporary politics as “little more than a spectacle of selfish ambition” and pledging to take the high ground. At the same event, however, his campaign passed out a news release falsely asserting that Mr. Bush’s “political” tax plan would “put Social Security in danger.” Mr. McCain was apologizing by the end of the day.

Operatives on both sides say Mr. McCain gave as well as he got for most of the race. “It was McCain on the stump fighting the ‘Death Star,’ ” — his epithet for the Bush juggernaut, Mr. Salter recalled.

But when his opponents unleashed anonymous phone calls and fliers spreading rumors about his family before the South Carolina primary, Mr. McCain fired back with a commercial accusing Mr. Bush of lying like President Bill Clinton. Its tone backfired, hurting Mr. McCain more than his target. Advisers pushed for a better attack but acknowledged they could not win the state. Instead Mr. McCain insisted on publicly apologizing and pulling the commercials. “So we died on higher ground,” said John Weaver, a former aide.

A few months later, Mr. McCain was back in the state apologizing for holding his tongue about his disdain for the Confederate flag to try to win the race.

“I will be criticized by all sides for my late act of contrition,” Mr. McCain declared. “I accept it, all of it. I deserve it.”

His loss in South Carolina made him a martyr: the politician too good for politics. “He came out of that primary the most popular politician in the country,” Mr. Weaver recalled.

“Is he crazy like a fox?” Mr. Weaver added. “Listen, he is a very good intuitive politician, and he is a lot smarter politically than those of us around him or he wouldn’t be where he is at.”

Former opponents marvel at Mr. McCain’s political alchemy. “He takes a past failing, hangs it around his neck, and wears it like a medal,” said Kevin Madden, who worked for Mitt Romney in the primary.

The Candidate

There is a part of John McCain that revels in his failures. “Sitting around, feeling sorry for myself” after losing in 2000 was “wonderful” he sometimes says. “Delicious,” he recalls, with sarcasm but also a certain relish.

His 2007 stint as the Republican front-runner did not go well. “I’m much better in this environment,” he said in South Carolina after his campaign was nearly broke, he had spiraled in the polls and shed much of his staff.

And winning can be imprisoning, Mr. McCain has found. For much of the summer, he had seemed merely dutiful on the trail, going through the motions. His aides have since imposed a new discipline, shielding him from the news media, scripting a daily message and reining in his tendency to improvise.

“At heart, he’s a maverick, and the maverick doesn’t like the corral,” said Mark McKinnon, a close aide to President Bush and Mr. McCain who is not involved in the campaign. “But the corral is where he is. And it’s working.”

Mr. McCain’s advisers say he hoped to pick up his 2008 campaign where his 2000 race left off — bucking convention, running against politics. He started his run against the Democratic nominee, Senator Barack Obama, with an apology. Standing on the balcony of the Memphis hotel where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, he told a mostly black crowd that he had made a mistake years ago in opposing a federal holiday for King.

He toured the heavily black areas of the South, an unlikely trip for a Republican running against an African-American. And for awhile, he skipped over the attack lines against Mr. Obama that advisers had inserted into his speeches. When Mr. Obama declined his invitation to a series of town-hall-style meetings, Mr. McCain went solo, drawing scant attention from the news media.

“None of it got through — nothing,” Mr. Salter said of Mr. McCain’s message.

By midsummer, Mr. McCain had put the campaign in the hands of Steve Schmidt, a former aide to President Bush (and a fan of Ultimate Fighting). The campaign began a barrage of advertisements that ridiculed Mr. Obama as a celebrity, accused him of indifference to wounded American soldiers, and asserted that he put politics ahead of victory in Iraq.

He stepped up his behind-the-scenes courtship of influential conservative leaders with whom he had clashed in the past. And he abandoned past calls for the party to moderate its opposition to abortion in order to let activists draft what many called the most conservative platform in the party’s history.

If Mr. McCain has any ambivalence about the conduct of his campaign, he no longer displays it in public. Friends say he wants to become president and is learning how to get there.

“John has always seen politics as an adventure,” his friend Mr. Graham said. “I’m trying to get him to think of it as a business.”

The choice of Sarah Palin exemplified both. Her resolute opposition to abortion fired up conservative activists to get out the vote for Mr. McCain’s election. But Mr. McCain’s advisers say he sees her the way he sees himself—as an upstart outsider who shook up her state’s corrupt Republican establishment. “The ‘old McCain’ is still there — look at the Palin pick,” Mr. Salter said.

The surprise was also a glimpse of how Mr. McCain might govern. Mr. McCain promises in every speech that as president he would put country first, but his notions of honor and disregard for his popularity can make him an unpredictable patriot. He is a conservative committed to limited government, except when he sees a greater cause like global warming, campaign corruption or children’s health. He boasts that he stood by the Iraq war long after the public turned against it, but also says he would never risk American troops abroad without deep public support.

His associates say Mr. McCain has come to see the presidential race in starkly moral terms, convinced that Mr. Obama’s election would weaken America at a decisive moment for the security of the world. But Mr. McCain is also the first to confess that not all his drives are so selfless.

“I didn’t decide to run for president to start a national crusade for the political reforms I believed in or to run a campaign as if it were some grand act of patriotism,” he wrote in 2002. “In truth, I wanted to be president because it had become my ambition to be president.” He added, “I had had the ambition for a long time.”

This story, Driven to Serve, and to Succeed, first appeared in The New York Times.