“Spore,” the latest creation from legendary game designer Will Wright, is massive.

First, let’s talk about scope. “Spore” takes on nothing less than the evolution of a species, asking players to shepherd a single-celled organism through five life phases culminating, eventually, with an attempt at global domination.

Making a game of this size is no small undertaking. Wright says the idea came to him about seven years ago, and it took another five years, and a team of 120, to make it real. Electronic Arts — which owns Maxis, the studio responsible for “Spore” — could have made two-and-a-half “Godfather” games in that time period.

But Wright’s games are — if you'll pardon the pun — game changers. “SimCity,” his first big-selling game, tasked players with — of all things — civic planning. Keep in mind that this was 1989, an era where video games were about diminutive plumbers named Mario, not mass transit systems for virtual constituents. The success of “SimCity” proved that teenage boys weren’t the only audience for video games, and it paved the way for Wright’s biggest game to date, “The Sims.”

That’s the other reason “Spore” is so huge: It’s the Next Big Thing from the guy who made the best-selling PC game in history — a “virtual dollhouse” in which players piloted little digital humans through ordinary digital lives. “The Sims,” which spawned many expansions and a massive fan base, helped to usher non-gamers into gaming.

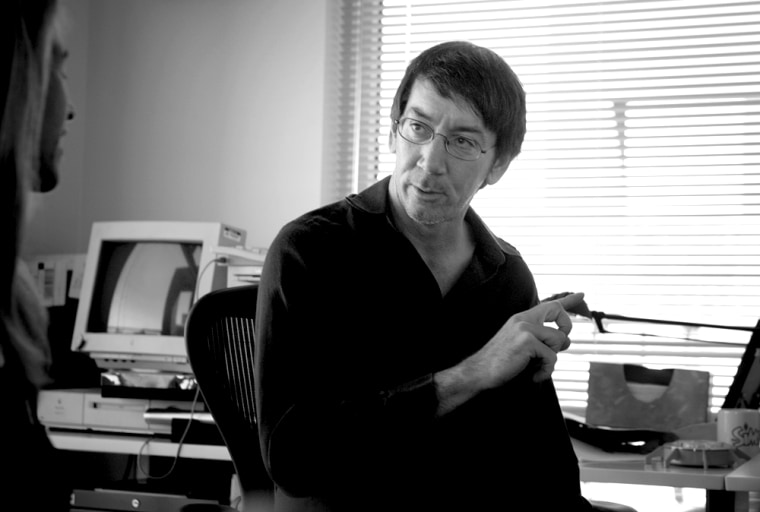

“I like to get people to think about the world around them, and have these little toy worlds in which they can run experiments,” he said during a recent interview. “I think of (games) almost like a modern chemistry set. “

Wright spoke to me via telephone from Florida, as a tropical storm blew overhead and made soggy work of his late-summer family vacation. During that conversation, the edited version of which follows below, Wright talked about “The Sims” — its astonishing lifespan and the importance of community participation to its longevity. We also talked about “Spore,” and the creativity he’s already seeing from players that downloaded the “Creature Creator” tool released earlier this summer.

How does it feel to finally get “Spore” out there?

It feels nice. It’s really interesting to see what the fans are going to do with it. We released the “Creature Creator” about a month and a half ago and so we’re already starting to see the weird creativity that comes into something like this.

Every level in “Spore” is so unique. The game goes from a microscopic Pac-Man level up to a level where you’re in space. How would you characterize — or categorize — a game that itself encompasses so many genres?

A basic rule of thumb is that you don’t want to be mixing genres, but another rule is that if you’re going to break a rule, you might as well thoroughly break it. Also, it seemed to fit, not only with the themes of each level, but there seemed to be something nice about leaving those themes and genres in the historical order of when they appeared in the game industry.

What was your reason for doing that?

It kind of fit, because the levels increase in complexity. And when you look back at the history of the game industry, games were increasing in complexity too. So, you have a 2-D scroller for Cell, a third-person action game for Creature, a real-time-strategy (phase) for Tribe and a more elaborate strategy for the Civilization level, and the space game is probably closer to a massively multiplayer online game, which is pretty much the historical order (that) they appeared in the game industry.

The technology driving “Spore” is pretty sophisticated stuff — user-generated content, procedurally generated content, social networking tie-ins. What technology are you most proud of in the game?

I’m not sure if you’d call it technology, but basically all the magic that brings to life the stuff the players make. That’s probably the very first thing that people hit and are really excited about. This has to do with the underlying procedural animation and procedural texturing … which is pretty interesting because we basically had to teach the computer to replicate a lot of what our artists do.

There’s quite a bit of artificial intelligence in the (creature) editor that makes it easy to use. Most people don’t realize that, they just think: “Oh, it’s easy to use.” But the computer is always kind of analyzing what it thinks you intend to do.

Do you think the technical accomplishments of this game are being overlooked? And is that by design?

At the end of the day, what you really want to deliver is an emotional entertainment experience to the player. And if the technology helps you accomplish that, great. But if it doesn’t, no amount of technology in the world is going to necessarily provide that. I think the technology is definitely in service of this other goal state. And whether or not the players know about that or appreciate it is really kind of irrelevant as long as we achieve that goal state.

You’ve said previously that “The Sims” really didn’t have much competition, other than, say, Second Life, which came much later. Do you think that “Spore” will stand alone as well — or do you hope that it doesn’t?

First of all, I don’t know if I would characterize Second Life as a competitor for “The Sims.” One is a game in which you’re creating stories, creating environments, playing with these little artificial people. Second Life is more of a graphic chat room. On the surface, they look kind of similar, but underneath, looking at the play experience, they’re really quite different.

And yes, it was surprising to me that we haven’t really had a viable competitor to “The Sims” since it was released. Which, I kind of almost would like to see at this point, to see what an alternative version of it would be. “Spore” … I’m not sure if it’s the kind of game that you’d really want to compete with. I can see taking aspects of “Spore” into other forms of gaming…the idea that players can create the content, for instance.

The game is very different than anything else that’s out there. And there’s so much pressure for this game to be revolutionary. How does that pressure affect you, considering your name is attached to it?

Well, at the end of the day, you want people to enjoy it. It’s getting a lot of visibility because it is different, and so when players interact with this thing, you kind of hope that they walk away from it with a different perspective than they can get from other games.

It’s actually kind of exciting where you have a game like this where the players get involved creatively and they start doing cool, amazing stuff. A lot of the success of “The Sims” was due to the players, and the player communities and what they were making in it and I think the same will be true with “Spore.”

So, not too much pressure on you, the pressure’s going to be shifting to the players?

Yeah, we’re going to share that pressure with the players. (Laughs) And they’ve already kind of surprised us with the depths of their creativity, so I have a lot of faith in them.

In your previous games, “SimCity” and “The Sims,” you were literally simulating real life. In “Spore,” you’re allowing players to travel through the life cycle of an organism. But much of the game is pretty fantastical — interstellar travel, cartoony-looking creatures. What was it like to create a game that wasn’t a strict simulation of real life? Was it freeing to work without those constraints, or was it maddening?

I think we learned a lot from some of the earlier simulations that we did –“SimEarth,” “SimLife” — in that you want to leave a big role for the player’s imagination. I think that helps a lot. Even though we’re dealing with these fantasy creatures, in some senses they’re still dealing with a lot of the same issues that humanity dealt with, evolving, building civilizations and so forth. That’s kind of the point. By seeing this occur with some alien species, it gives you a different triangulation on what it means to be human. What’s the meaning of competition and cooperation, sociology, religion and economics? All these themes that we’re familiar with, we’re just not playing out the history of mankind.

In some senses, yeah, it’s creatively very freeing. You’re dealing with a much larger potential palette…and it gives you a wider palette of stories that players will use in their storytelling. But at the same time, it should all feel fairly familiar and be something you can relate to on some level.

You mentioned at the Technology, Entertainment and Design conference in Monterey, Calif., that you think of video games as toys. Considering that the average age of game-players is around 32, are you making toys for adults that don’t want to grow up?

(Laughs) Well, I don’t necessarily think of toys as a kid thing. I think of them as abstract little mechanisms that we can manipulate model worlds with, in our heads. In some senses, they’re tools for imagination. We tend to think of kids as imaginative … and it’s kind of “taught out” of us, as adults. I think of the best toys as things that can spark and enhance your imagination. I think that imagination is probably our most powerful tool.

What do you think about the current level of innovation and creativity in the game industry today?

I think it’s gotten a lot better over the last few years. I think primarily because the market has started to broaden out a lot because of things like the Nintendo Wii. We’re starting to hit different groups of people that didn’t play games before, and so I think we were stuck in this chicken-and-egg thing before, where we only made games for gamers because gamers were the only ones who bought games.

“The Sims” is the best-selling PC game in history, but at the time it was released, it was pretty unlike any other game on the market. Do you think a game like “The Sims” would be greenlighted today?

I think it might be today, again, because of this explosion of game diversity that’s happening. But I think five years ago — probably not. I remember I had a long, uphill battle convincing people that we should do “The Sims” because it didn’t match any known genre, and, worst of all, it didn’t sound like an empowering game. You know, it was a game where you’re cleaning the toilet and taking out the trash and most games were about saving the galaxy. I think the fact that it ended up being a very deeply personal experience for players was a lot of the elements of the success of the Sims.

Your interests outside gaming include science, space travel and robotics. And your games definitely don’t fit the mode of traditional video games. So, do you consider yourself a video game designer, or a scientist who’s performing experiments through video games?

(Laughs) I think it’s more like I’m a video game designer who wants to make other people feel like scientists.