They may have been stronger, but Neanderthals looked, ate and may have even thought much like modern humans do, suggest several new studies that could help explain new evidence that the early residents of prehistoric Europe and Asia engaged in head-to-head combat with woolly mammoths.

Together, the findings call into question how such a sophisticated group apparently disappeared off the face of the earth around 30,000 years ago.

The new evidence displays the strengths and weaknesses of Neanderthals, suggesting they were skilled hunters but not as brainy and efficient as modern humans, who eventually took over Neanderthal territories.

Most notably among the new studies is what researchers say is the first ever direct evidence that a woolly mammoth was brought down by Neanderthal weapons.

Margherita Mussi and Paola Villa made the connection after studying a 60,000 to 40,000-year-old mammoth skeleton unearthed near Neanderthal stone tool artifacts at a site called Asolo in northeastern Italy. The discoveries are described in this month's Journal of Archaeological Science.

Villa, a curator of paleontology at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, told Discovery News that other evidence suggests Neanderthals hunted the giant mammals, but not as directly. At the English Channel Islands, for example, 18 woolly mammoths and five woolly rhinoceroses dating to 150,000 years ago "were driven off a cliff and died by falling into a ravine about 30 meters (over 98 feet) deep. They were then butchered."

Villa, however, pointed out that "there were no stone points or other possible weapons" found at the British site.

"At Asolo, instead there was a stone point that was very probably mounted on a wooden spear and used to kill the animal," she added.

Several arrowheads were excavated at the Italian site, but the one of greatest interest is fractured at the tip, indicating that it "impacted bone or the thick skin of the mammoth."

Other studies on stone points suggest that if such a weapon were rammed into a large beast, it would be likely to fracture the same way.

What's for dinner?

There is no question that Neanderthals craved meat and ate a lot of it.

A study in this month's issue of the journal Antiquity by German anthropologists Michael Richard and Ralf Schmitz found that Neanderthals went for red meat, not of the woolly mammoth variety, but from red deer, roe deer, and reindeer.

The scientists came to that conclusion after grinding up bone samples taken from the remains of Neanderthals found in Germany and then analyzing the isotopes within. These forms of chemical elements -- in this case, carbon and nitrogen -- reveal if the individual being tested lived on meat, fish or plants, since each food group has its own carbon and nitrogen signature.

Richard and Schmitz conclude that the Neanderthals subsisted primarily on meat from deer, which they probably stalked in organized groups.

The researchers say their findings "reinforce the idea that Neanderthals were sophisticated hunters with an advanced ability to organize and communicate."

Villa agrees.

"Neanderthals are no longer considered inferior hunters," she said. "Neanderthals were capable of hunting a wide range of prey, from dangerous animals such as brown bears, mammoths and rhinos, to large, medium and small-size ungulates such as bison, aurochs, horse, red deer, reindeer, roe deer and wild goats."

Enter Homo sapiens

Fossils suggest that Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted in Western Europe for at least 10,000 years. While there is a smattering of evidence that the two species interbred, most anthropologists believe the commingling was infrequent or not enough to substantially affect the Homo sapiens gene pool.

New evidence supports that notion, while also revealing that the world's first anatomically modern humans retained a few Neanderthal-like characteristics.

Several papers in the current Journal of Human Evolution describe the world's first known people, which shared bone, hand and ankle features with Neanderthals and possibly also Homo erectus.

John Fleagle, professor of anatomical sciences at Stony Brook University, who worked on the early human research, told Discovery News that the shared characteristics "are just primitive features retained from a common ancestor."

It's known that Neanderthals had more robust skeletons than modern humans, with particularly strong arms and hands, but were the two groups evenly matched in brainpower?

A new study in this week's Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences provides some intriguing clues.

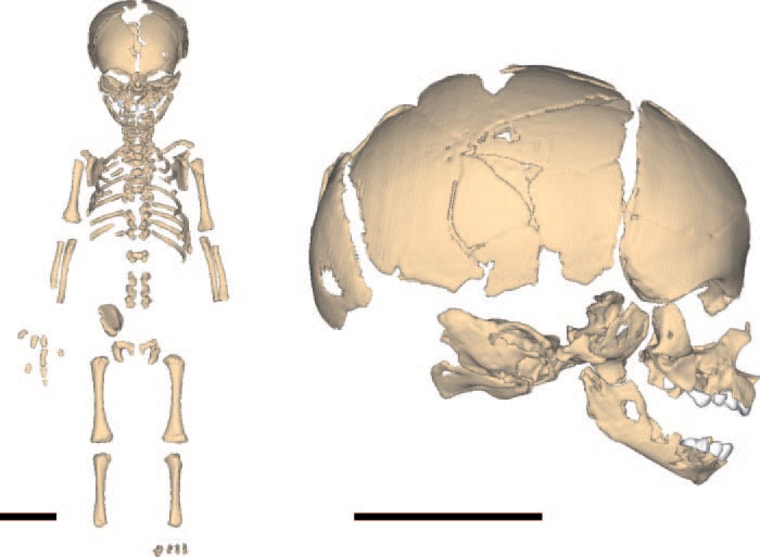

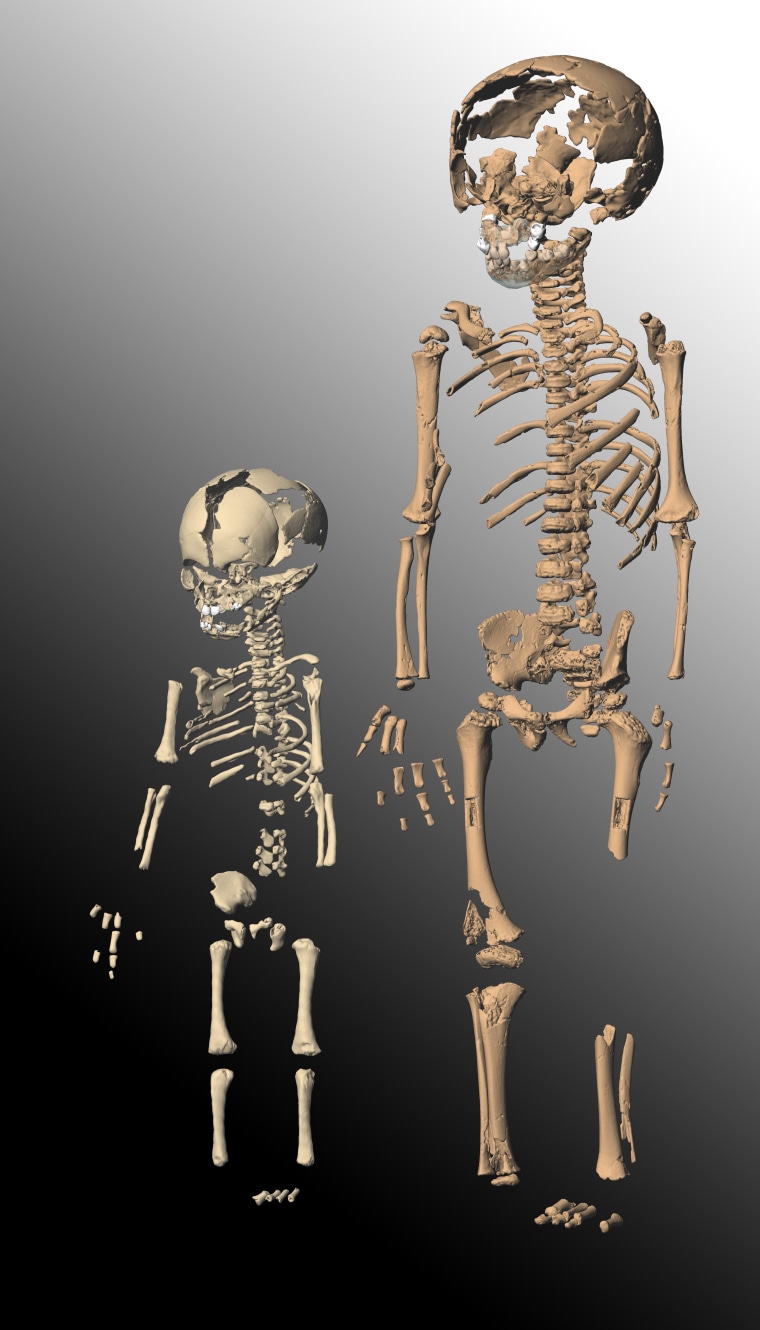

Marcia Ponce de Leon of the University of Zurich's Anthropological Institute and Museum and her colleagues virtually reconstructed brain size and growth of three Neanderthal infant skeletons found in Syria and Russia.

"Neanderthal brain size at birth was similar to that in recent Homo sapiens and most likely subject to similar obstetric constraints," Ponce de Leon and her team concluded, although they added that "Neanderthal brain growth rates during early infancy were higher" than those experienced by modern humans.

It appears, therefore, that while Neanderthal brains grew at about the same rate as ours, they had a small size advantage.

Brainpower trade-offs

But bigger is not always better in terms of brain function. Modern humans evolved smaller, but more efficient, brains.

Ponce de Leon and her colleagues suggest, "It could be argued that growing smaller — but similarly efficient — brains required less energy investment and might ultimately have led to higher net reproduction rates."

On the down side for people, however, brainpower efficiency doesn't come without a cost.

"Our new research suggests that schizophrenia is a byproduct of the increased metabolic demands brought about during human brain evolution," explained Philipp Khaitovich of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the Shanghai branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Weighing the pros and cons of each species, Neanderthals and modern humans may have been evenly matched when they shared European land, with more and more scientists puzzling over how such an advanced, human-like being became extinct.

University of Exeter archaeologist Metin Eren hopes the latest findings will not only change the image of Neanderthals, but also the direction that future research on these prehistoric hominids will take.

"It is time for archaeologists to start searching for other reasons why Neanderthals became extinct while our ancestors survived," Eren said.

"When we think of Neanderthals, we need to stop thinking in terms of stupid or less advanced and more in terms of different," he added.