After a widely heralded startup, the world's largest particle collider has suffered two malfunctions in the past week — setting off two separate rounds of troubleshooting.

The first problem with the Large Hadron Collider occurred within hours of the $10 billion project's official launch on Sept. 10, but the operators at Europe's CERN particle-physics center didn't make the glitch public for a week.

The collider was briefly brought back into operation on Thursday, but sensors detected a large helium leak from the device's cooling system during testing on Friday. That forced another shutdown, and an investigation of the problem was expected to continue through the weekend.

CERN spokesman James Gillies told msnbc.com that no one was in the collider's 17-mile-round (27-kilometer-round) underground tunnel when the mishaps occurred. CERN still plans to begin collisions at the LHC sometime in the next few weeks, he said.

The first glitch, on Sept. 11, involved the breakdown of a 30-ton transformer that cools part of the collider. When the transformer malfunctioned, operating temperatures rose from below 2 Kelvin to 4.5 Kelvin (-456.1 to -451.6 degrees Fahrenheit). The warmer level is still extraordinarily cold by most standards, but above the collider's normal operating temperature.

That forced a days-long shutdown. The faulty transformer was replaced, and the magnet ring was cooled back down to its operating temperature.

Gillies said the machine was "back up and running" on Thursday. However, the collider's monitoring system detected a helium leak in one of the collider tunnel's sectors on Friday while technicians were testing the electrical circuitry for that sector, he said. The collider's magnets rose to temperatures in the neighborhood of 100 Kelvin (-279.7 degrees F), and the system was shut down again for an investigation.

Gillies said the circuit test likely caused the leak, but the precise cause was not immediately known. "There are several thousand amps of current [in the circuitry], so it's very high current," he said.

Physicists said it isn't that surprising that problems would occur in the process of getting a huge and immensely complicated collection of equipment like the Large Hadron Collider up and running smoothly.

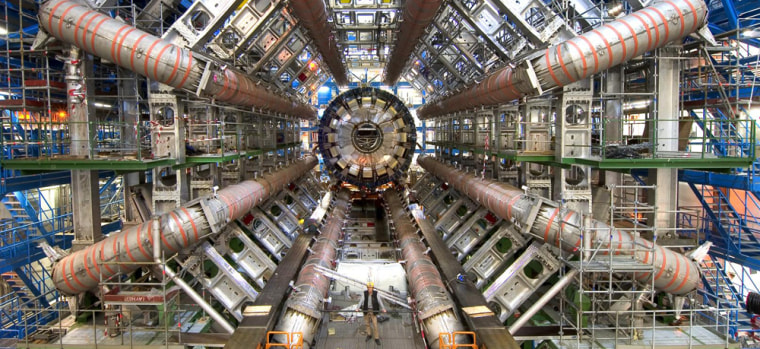

"This is arguably the largest machine built by humankind, is incredibly complex, and involves components of varying ages and origins, so I'm not at all surprised to hear of some glitches," Steve Giddings, physics professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara. "It's a real challenge requiring incredible talent, brain power and coordination to get it running."

Judith Jackson, spokesman for the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill., echoed that view.

"We know how complex and extraordinary it is to start up one of these machines. No one's built one of these before and in the process of starting it up there will inevitably be glitches," she said.

Fermilab is home to the Tevatron, an accelerator that collides protons and antiprotons in a 4-mile-long underground ring to allow physicists to study subatomic particles. Until the LHC's startup, the Tevatron was the world's most powerful particle collider.

The Large Hadron Collider is designed to collide protons in the beams so that they shatter and reveal more about the makeup of matter and the universe.

After it was started up Sept. 10, scientists circled a beam of protons in a clockwise direction at the speed of light. They shut that down, then turned on a counterclockwise beam. Scientists said the beam made several hundred circuits around the ring.

On the evening of Sept. 11, scientists had succeeded in controlling the counterclockwise beam with equipment that keeps the protons in the tightly bunched stream that will be needed for collisions, but then the transformer failed and the system was shut down, the statement said.

This report includes information from msnbc.com and The Associated Press.