It was shaping up as a perfect afternoon when Kipp Landis climbed aboard the doomed Metrolink 111 train at Union Station.

Landis had managed to get away from his law office early, giving him just enough time to catch the 3:35 p.m. train to Moorpark to coach his 5-year-old son Jett's soccer team. Along with his briefcase, he was carrying a dozen Krispy Kreme doughnuts for his players.

Before leaving the station, train engineer Robert Sanchez, a diabetic, phoned in his dinner order to a deli just down the street from Metrolink's Moorpark station, the last stop on his run. He told Hub Hoagies 'N More owner Randy Richardson he'd be there about 4:30 p.m. to pick up the roast beef sandwich — no onion, no tomato, extra light mayo and Italian dressing.

Neither Sanchez nor Landis would make it to that final stop.

Sanchez would die in the cab of his locomotive after driving through a red light and head-on into a freight train, killing 24 passengers. Landis would join many of his fellow passengers at an emergency room, fighting for his life.

The tragedy of Sept. 12 would forever alter the lives of hundreds of people, from the 222 on board to those who should have been on the train but missed it, to the relatives of riders who were killed, to the veteran first-responders who labeled it the most horrific thing they'd ever seen.

'A beautiful day'

For Landis, the ride home began uneventfully with him taking his usual seat in the train's first car.

"It was a beautiful day, it was perfect," he recalled, describing one of those idyllic, sun-splashed Southern California afternoons seen on postcards.

A Metrolink rider for nearly 13 years, he ignored warnings of friends who called the front of the train the "suicide car." He figured he'd be safe as long as he sat with his back to the engine so that he wouldn't pitch forward if the train hit something. It never occurred to him that the train might run head-on into an oncoming locomotive going 40 mph.

The first 45 minutes of the ride were uneventful. Landis chatted with a young woman he worried would doze off and miss her stop.

She got off at the Chatsworth station, and about two minutes later — 4:22 p.m. — the 42-year-old attorney and Moorpark planning commissioner heard a gigantic bang.

"The next thing I remember, I was telling myself to breathe," Landis said from his hospital bed at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center last week.

'So much carnage'

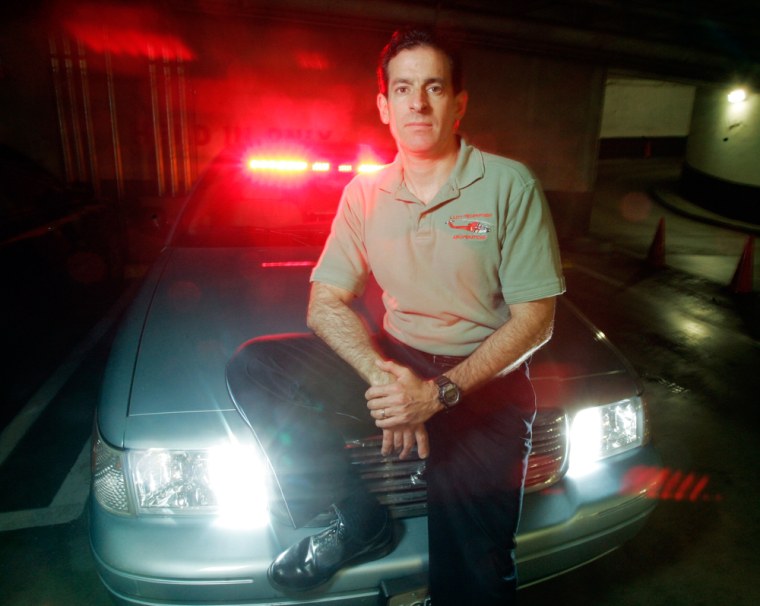

Minutes after the crash, Dr. Marc Eckstein was pulling up to his San Fernando Valley home when he heard a bulletin on the radio about a train crash.

Eckstein, medical director for the Los Angeles Fire Department, put the car's emergency lights and siren on and raced to the scene 10 minutes away. A veteran of earthquakes, deadly fires and a 2005 Metrolink train crash that killed 11 people, Eckstein was stunned by what he saw.

"I've been doing emergency medicine for 25 years," since he was a teenage paramedic in New York in the 1980s, said Eckstein, 44. "I have never seen so much carnage like this in one place in my career."

Firefighters from nearby Station 77 could see smoke rising from the freight train's locomotive as they arrived. It was engulfed by flames, and two of its crew members were trapped inside and frantically pounding on the windshield for help.

"That was a challenge, getting through that front windshield, because it's essentially like bulletproof glass. And they got those guys out, saved their lives," said fire Capt. Thomas Moore, 49. He said firefighters try to focus on moments like those rather than dwell on the people they couldn't save.

Near the fire, the Metrolink's locomotive was embedded in the first passenger car. Eckstein could see bodies of several riders ripped to pieces and intertwined with metal debris from the train. Some were stacked on top of injured passengers.

A train lover dies

Among the dead was Alan Buckley, 59, who may have been Metrolink's biggest fan. He was riding from his home in Simi Valley to his job as a mechanic for the city of Burbank since 1992, the year the agency inaugurated commuter rail service.

His father had been a railroad switchman and he had been fascinated with trains since he was a child. He loved trains so much that he once sent his mother a postcard of the one he rode with the words: 'This is the train I take back and forth to work. The greatest thing that's ever happened to me.'"

"And that's what ended up killing him," said his son, Jeff Buckley, his voice choked with emotion.

Like Landis, Buckley had been seated in the front car. He rode in the back on the way to work and in the front on the way home because that's where his buddies sat.

Jerry Romero should have been in the train's second car, but he wasn't.

He decided at the last minute to drive to work that morning so he could pick up his new bicycle. He was at a Studio City bike shop when his frantic father called to find out if he was all right.

"Somebody made the statement to me about my being lucky, how I should be thankful, be happy," said Romero, 43. "But what I'm wondering is when I'm going to feel that."

Had he been on the train, he said, perhaps he could have helped some of the injured.

"It's a hard feeling to get out of your mind," he said.

Broken bodies

Landis is unsure how long he was unconscious, but when he awoke he was trapped in the wreckage with a pair of firefighters standing above him, trying to get him out.

Another passenger was shouting for help. Saws were cutting through metal somewhere else on the train.

His cell phone was ringing nonstop but he couldn't move his arm to answer it. It was his wife who had been waiting for him at the train station with their three sons, ages 7, 5 and 1 month, and who was becoming increasingly certain with each unanswered call that he would never answer.

"I thought my arm was cut off," Landis said. "There was an arm laying across my body ... and I was touching the arm. So I told the firemen my arm had been severed. But I could hear the firemen talking to each other, and they said 'No, that's a DB.' A dead body."

It had landed on top of him.

The first car had indeed been the deadliest place to be. But the impact was so severe that even people in the rear car had been killed.

"I found two bodies on a staircase in the third car, one on top of the other," Eckstein said.

Landis was one of the first to be flown by helicopter to a hospital. He was relieved when he was finally in flight, but he worried when doctors said they wanted to put him in a medically induced coma while he recovered from serious internal injuries.

He had suffered a bruised heart, bruised lungs, broken ribs, a broken back, broken arm, fractured sternum, internal bleeding and had a wrist dislocated so badly it would need surgery.

Doctors were able to keep him conscious during his recovery. After five days in intensive care, he was transferred to a regular hospital room. He took his first steps Tuesday, but he doesn't expect to be going home anytime soon.

'I hope he died peacefully'

When Metrolink resumed service Monday, Romero returned to the train, and he and other emotional passengers hugged and wept.

He posted a note at the Simi Valley station listing fellow riders he knows only by first name and asking them to call and tell him they're OK.

He found himself paying more attention to anyone he has a chance encounter with, not just his train friends. He'll pause to smile and say hi, and one day last week he picked up some Mickey Mouse stickers at work and handed them out to everyone in the second car.

"Things are starting to get back into place," he said, striking a more upbeat tone. "I don't know if it will ever get back in place to the full extent, but it's getting there."

Buckley had told his family that when he died he wanted to be cremated and his ashes scattered from the back of a train.

His son doubts that it's legal to spread the ashes from the back of the train, but his family hopes to scatter them off a bridge above the tracks.

"He died truly doing something he loved," Buckley said of his father. "But I hope he died peacefully and not in some mangled steel. That's a hard thought to get out of my head."