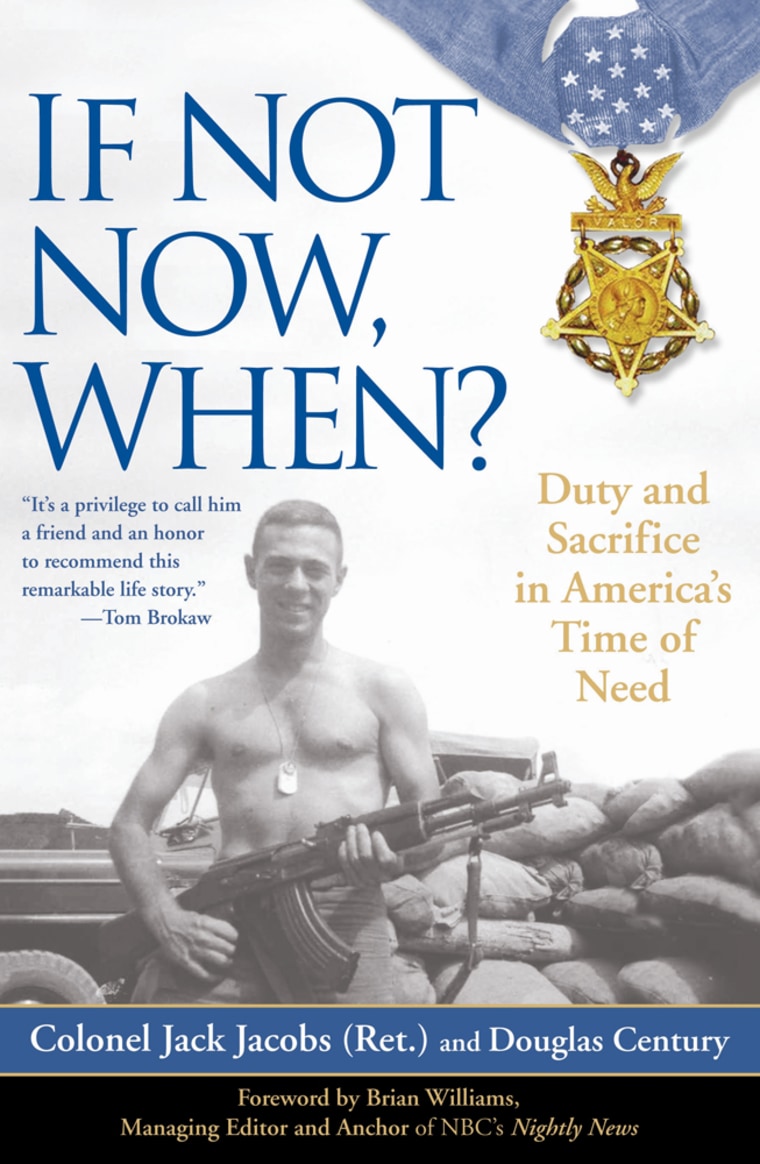

With candor, humor, and quiet modesty, Medal of Honor recipient Col. Jack Jacobs tells his stirring story of heroism, honor, and the personal code by which he has lived his life. He looks back at his service and ahead to America’s future, and shares insight on his views on our contemporary world, and the nature and necessity of sacrifice. Read the foreword below, from NBC’s Brian Williams; and Jack Jacobs’ prologue.

The Man in Seat 2B

Foreword by Brian Williams

Anchor and Managing Editor, NBC Nightly News

My favorite Jack Jacobs story takes place not on the field of battle, but in the office of the chief investment officer of an insurance company in Germany. Jack flew there on business a few years back, hoping to free the executive of twenty million dollars toward a hedge fund Jack was developing back in New York, where he enjoyed a successful career on Wall Street while working for Bankers Trust.

Jack being Jack, he remembers wondering how many of his fellow Jews, perhaps even members of the Jacobs family, had gone to their reward at the hands of the banker’s relatives during World War II. At that instant, however, Jack wasn’t about moral judgments. His mission was to leave the meeting with a pile of money neatly but figuratively stacked in his briefcase. That was the mission.

So the meeting starts, and during the conversation, Jack was, as he later put it, “absently scratching at a tiny bump” near his nose. As quickly as you can say hemorrhage, Jack breaks something loose that causes “a torrent of venous blood that splattered everywhere,” down the front of his clothing, the coffee table and ending up on the hand-knotted Heriz rug beneath their feet.

Jack remembers it looking like a crime scene. In an attempt to regain control of a business meeting that had taken a sudden and bloody turn south, Jack mumbled an explanation about residual injuries from his time fighting in Vietnam. It was apparently enough for the stunned German: Jack left the room with the twenty million dollars he’d come there asking for. It would more than pay for a new rug. Hand-knotted, no less.

What happened that day isn’t at all uncommon for combat veterans: a piece of shrapnel had taken thirty years to come to the surface. The same can be said of the story contained in this book.

Countless business travelers have sat next to my friend Jack for long flights across the Atlantic. If asked, they’d later describe the man in seat 2B as diminutive, smart, a cheerful guy and a wonderful storyteller. They would be stunned to learn he also happens to be a recipient of the Medal of Honor.

That’s the thing about Jack. That’s also the thing about all the other guys just like him—all of the men alive today who have been awarded the nation’s highest decoration for bravery and valor in battle. I have come to know them by serving on the board of directors of the Medal of Honor Foundation. At the time of this writing, there are just over one hundred men alive who are members of this exclusive group. Our board is charged with raising money to promote awareness of the Medal of Honor and what it represents. The truth is: I would pay them to be on their board. Being around these men, getting to know them has been among the great ongoing experiences of my adult life.

I’ve known Jack the longest of any of the recipients, because of our time together at NBC News, where Jack has come to on-air prominence as a military analyst. Like most of the tasks he has tackled in life, it comes to him seemingly effortlessly, and he’s awfully good at it. Far from being a pushover for the Pentagon, and despite his retirement rank of Colonel following his years of proud service and multiple combat tours, Jack calls them as he sees them, and is an unsparing critic of U.S. policy when circumstances require it.

I also thought I knew him. Because I have read his medal citation many times over, I rather proudly assumed I knew the details of his Vietnam experience, and of the military engagement that led to the medal being placed around his neck by President Richard Nixon. While I’ve flown all over the country with Jack, and spent countless hours happily engaged in conversation with him, it turns out I knew but a fraction of his story.

The living recipients of the Medal of Honor are walking monuments to modesty, Jack chief among them. Most of the warriors I know hate war. Jack’s humility and complete lack of swagger are striking. Jack Jacobs is a complete American. He has lived the American experience, while rising out of bed to greet each new day as the sole occupant of a badly broken vessel—his body, like an old house, is full of combat scars and residual shrapnel, and requires constant upkeep: frequent operations to improve plumbing and ventilation. This man who carries around tiny pieces of steel still believes he has grabbed life’s brass ring, won the lottery, beaten the odds. He is a patriot of the highest order, in the truest sense of the word, in the tradition of those who have fought hard enough for this place to come down hard on us when they fear we’re heading off in the wrong direction.

When I speak to audiences about the lessons I’ve learned from my recipient friends, I always say the same thing: before I met them I used to think I had an occasional bad day. Never again. Not as long as there are men like Jack Jacobs to remind us all how much a human can endure, and how much this nation means to the people who’ve fought for it.

One warning: the book you are about to read, at its core, is a story about selflessness, sacrifice, and service, and it collides loudly and rather violently with much of our current culture. We are presently a nation of 120 million blogs and bloggers. Put differently, 120 million of us are enthused enough with our own stories—convinced enough in our own wisdom and wonderfulness of self—to believe there is great utility in posting our every thought, desire, and daily movement on the internet, presumably for the common good, the benefit of all. Jack was handed a weapon and told to use it on foreign soil to defend his brothers and his country. As you read this, ask yourself which of the two actions you find more heroic.

I’m convinced you’ll come away staggered by the diminutive man in seat 2B. I will never view my friend Jack in the same way again. I just didn’t think it was possible to admire him any more than I already did.

Courage is the art of being the only one who knows you’re scared to death. — Harold Wilson

Prologue

IV CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

KIEN PHONG PROVINCE

REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM

9 MARCH 1968 0830 HOURS

In the morning heat, moisture on the surface of the Mekong rises slightly over the widening mass of water upriver in Cambodia and then, just after dusk, condenses on its lazy southerly journey through Vietnam. The following dawn, there is always a thin mist skimming the river, even in early March, well before the worst of the wet season, when the torrential sheets of rain have left the landscape a flat carpet of green. That spectral shroud follows the river and dances slowly with it on its trip through the Vietnamese delta, until the wide, muddy Mekong is swallowed whole by the South China Sea.

Just after sunrise on March 9, 1968, a few decrepit and dented assault craft nose slowly through the thin tropical fog, diesel engines chugging cautiously. Lesions of rust leach through the battleship-gray paint of the boats. They are packed with South Vietnamese soldiers bending under the weight of weapons, ammunition, and the weariness of combat. Since the beginning of the Tet Offensive less than two months ago, many of the battalion’s troops have been killed or wounded, and only about two hundred soldiers are on the boats.

I am twenty-two years old, rail-thin and infantry dark. At a shade under five feet four, I am shorter than most of the Vietnamese. My journey has taken me from an immigrant Jewish family in Brooklyn, New York, to the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry of the 9th Infantry Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, a universe away from home and in fear of my life in an alien land. I look like a child. I am a child.

There are three other Americans serving as advisors with these Vietnamese soldiers, but we aren’t temporary interlopers. The 2nd of the 16th is our battalion. We live with the Vietnamese, share their meager rations, fight at their sides, call them friends, and watch them bleed and die.

It begins as just another mission to reestablish contact with the Vietcong unit we have been fighting for months, and when the ragged old boats slide onto the muddy bank, we plan to pick our way slowly, tentatively, from one tree line to another, across wide, open rice paddies that will give any hidden enemy unobstructed fields of fire onto our unit. There are two of us Americans with the lead companies of the battalion. My NCO, Ray Ramirez, is five feet seven inches tall and strong as an ox, a brave, plainspoken staff sergeant with a thick Mexican accent and an even thicker bull neck. Ramirez is from Raymondville, Texas, near Brownsville—he says it’s close enough to Mexico to actually be in Mexico.

Ray and I are in the lead boat. With a gentle bump, the groaning old tub finally wedges against the mud on the north side of the river, and we trudge ashore through the eerie morning mist and the thick, smelly muck to the dense undergrowth at the river’s edge. We clamber noisily down the slippery embankment of a narrow canal and up the steep opposite side to a vast dry rice field to be greeted by the stinging glare of the newly risen sun. Cautiously, we straggle across the first paddy, almost a thousand meters of open field.

There is no cover here, I think. No concealment whatsoever. We are in the worst tactical position imaginable. We have several hundred troops in the open, marching slowly toward a specific, predetermined point, and we possess no element of surprise. Our only protection is one half-strength, half-trained scout platoon covering our nakedness to the front and flanks. Half of a half. One-quarter of the minimum protection we need, if it’s really there.

Well, the scouts are somewhere, but as we will discover to our surprise and great pain, they aren’t protecting us. They are to the rear perhaps, at home maybe, but they aren’t where they are supposed to be. We are where the scouts are supposed to be. We’re the leading edge of what is to become the juicy target of an ambush that was prepared for us by an enemy that has known long in advance that we are coming, and that we are coming in this strength, at this time, to this specific point on the ground. Three hundred enemy soldiers have spent days assembling themselves into the largest, best-armed, most cohesive Vietcong unit in the region. And now they wait for us.

This close to the equator, the sun leaps quickly from its berth just below the horizon to its place of business directly overhead. It is an insistent, fiery ball that refuses to relinquish its station until it is forced from the sky. By midmorning, we have been mooching toward our objective for several hours, and the sun has been pounding us, roasting us in our own salty juices that stain uniforms a starchy, brittle salt-white.

Dehydrated now. Tired. Head-heavy. Looking down rather than forward. Searching the ground and not the horizon, tracking the drops of perspiration as they fall and then splatter when they hit the earth. Glancing about for the scouts and hoping that they are protecting us forward and to the flanks. The VC will see the scouts first. Three hundred enemy guns will aim for the center of mass of the scout platoon, and we will maneuver the lead companies to destroy the VC, and Ray and I will survive yet another day and then go home without a scratch.

Though we don’t know it yet, two hundred meters ahead of us, about a battalion of Vietcong are waiting for us. They are not waiting for the scouts. They are waiting for me and for Ray. They are patient, quiet, disciplined, concealed.

One hundred meters now. I know how the VC feel, energized with the grisly knowledge that other human beings have only minutes to live and yet don’t know it.

I have lain in ambush, too, and I know how the Vietcong soldier feels when he sees Ray and me and the Vietnamese troops move cautiously forward. We are almost close enough, but not quite, and he suddenly realizes that in his excited anticipation he has been holding his breath and needs precious oxygen. A slow, deliberate inhale of thick air, but the sound is startlingly loud to him. We will hear his straining lungs fill, will fall to the ground, and will pour withering fire into his foxhole, tearing him apart. His mouth is cotton-dry, and surreptitiously he tries to swallow, but his throat reverberates deafeningly. The point man will hear him breathe, hear him swallow, hear him blink. The telltale heart is slamming wildly inside his chest. He will be discovered in ambush, and he will become the prey, and he will be destroyed.

Fifty meters. When we get to the tree line, maybe we can take a break, relax, light up, take a drunken slug from our canteens.

All experience inoculates us with the ability to sense the environment in indefinable ways, and nothing is better at honing the senses than armed combat. The wind is a messenger: a whisper, a falling leaf, even silence becomes palpable. They are urgent messages that bypass our consciousness and are transmitted directly to those secret places in the heart that can see what the eyes cannot see, the places that understand passion, euphoria—and danger. The unforgettable smell of death before the first insult to the body. The paralyzing cold of abject fear even in the warm caress of the sunshine.

And in the heat of the tropics, I suddenly feel the cold. It’s not a breeze, for the air is calm, even sweet, and just ahead the palm and banana fronds hang limply in the heavy air. But I can feel the penetrating cold of approaching fear, and it is a wind boring through me. An uneventful day so far, and yet my heart is racing. Maybe I can hear the VC breathing, swallowing, blinking, and I don’t even know I can hear it.

Suddenly the universe erupts with rifle and machine gun fire, and in seconds dozens of soldiers are thrown to the ground by the enormous energy of high-powered military bullets. My friends don’t grasp their wounds and slowly slink to earth in a theatrical, ceremonious ballet. There is no stirring Hollywood score. These notes are the shattering cracks of thousands of bullets and the nauseating thumps as they hit the flesh and bone of my comrades. They are marionettes whose strings have been cut, lying dead or hideously broken. A few of us are lucky so far, and we hug the ground like desperate lovers, unscathed in the initial seconds but scared witless.

We learn as young soldiers that an ambush is best defeated by rushing directly into the teeth of it, by suspending fear and disbelief, by getting off the killing ground, by assaulting directly into the withering fire to overrun the enemy position. And surely there have been ambushes that didn’t succeed because soldiers in the killing zone did just this, just as they had been taught.

But today, there will be no concerted effort to rush the entrenched enemy because this is a battlefield on which almost everybody is in the open and already dead or wounded.

We manage to crawl a bit to the left and out of the most direct enemy fire, to a place where there is a tree or two and a bit of protection. Some soldiers, wounded in the first seconds, are on the ground there, their lives leaking onto the dark earth while the enemy fire splits the air and tears into the dirt around us.

Some people say that you can’t hear mortar rounds until they hit because mortars are high-trajectory weapons and most of them are stabilized silently with fins. Unless the firing battery is close enough for you to hear the rounds sliding down the tube, before they are propelled out of the barrel in a slow arc to your position, you don’t know you’re a target until the rounds hit the ground. Quiet death, they say.

They’re wrong. In the last second before the round hits and disintegrates, before the explosive inside the shell shatters the steel casing into thousands of jagged, knife-sharp shards, I can hear it whooshing through the air. After the whoosh comes an explosion so loud that it overloads my hearing and seems silent.

A quiet, warm, gentle rush of air lifts me, and then I am on all fours, looking at the ground and the widening lake of my blood. An 82-millimeter mortar round has smashed into the ground a couple of meters away, killing two soldiers nearby, wounding Ray and me, and killing two or three more behind us. Shrapnel has torn through my face and into my skull. I can only see out of one eye.

Then more mortars rain on us all.

There is no fear on earth like the fear of combat, and people who say they were not scared in battle are either lying or deranged. You are in fear of losing your life, of losing your limbs, of losing your courage. In the heat of battle, everyone is scared. But here is the paradox: when you’re hit, when jagged foreign objects rip painfully through your body, you’re surprised, even shocked.

Beside me, Sergeant Ramirez is very badly hurt, with wounds to his chest that are deflating his lungs, shrapnel in his abdomen, blood pouring out of his nose and mouth.

Despite his devastating wounds, Ray grabs one of the radios.

“This is Three Two Charlie,” Ramirez barks into the handset. “Three Two Alfa is hit real bad, and I don’t think he’s going to make it.” He then sags under the crushing insult of his wounds and falls over, painfully immobilized, eyes lolling backward. I snatch the handset from him.

“This is Three Two Alfa,” I’m saying. “Three Two Charlie is hit real bad, and I don’t think he’s going to make it.”

Someone on the other end of the radio says, quite calmly:

“Hey, you jerks. This is no comedy routine. Get to work.”

I patch up Ray as quickly as I can and set him in a place where I hope he’ll be safe. But he is badly wounded. My greatest fear is that he won’t make it....