As NASA marks 50 years of space exploration on Wednesday, it’s also looking for bold new ways to get humans and robots working together for the next 50 years on the final frontier.

Over the past half-century, robotic and human exploration have been put in separate pigeonholes — one for moonwalkers, another for Mars landers. But if NASA’s vision for the future pans out, your children won’t be able to think about how astronauts do their work without remembering their trusty robotic sidekicks as well.

NASA's plans to fix the Hubble Space Telescope, finish the international space station and eventually return to the moon provide prime examples of the challenges facing NASA 50 years after its founding — as well as the strategies to meet them in the next half-century.

Right now, NASA's most pressing problem is figuring out how to bridge the gap between the space shuttle fleet's scheduled retirement in 2010 and the expected debut of a new spaceship for human spaceflight by 2015. The current plan calls for the space agency to rely on other countries and private companies for space station resupply during the five-year gap, although the next president may want NASA to delay the shuttles' retirement instead.

If you broaden the focus from five years to 50 years, the issues shift to the bigger picture: Will NASA be a scientific agency, sending out robotic probes to unlock the secrets of the solar system and beyond? Or will it devote more of its resources to exploration, following a step-by-step campaign to station humans on the moon?

NASA Administrator Michael Griffin argues that the agency has to continue to do both.

"Our robotic science program is about scientific discovery," he told msnbc.com in a July interview. "That's crucially important, and you'll never get me to say otherwise. But human spaceflight is about expanding the range of human interaction, and I think that also is crucially important. They are not the same thing. ... NASA has to be able to walk and chew gum at the same time."

Robots vs. humans?

To this day, scientists and policy experts debate which side of NASA — robots or humans — has provided the most bang for the buck. Roughly 60 percent of NASA's $17.3 billion budget went to manned exploration this year, with another 30 percent going to space science and the rest divvied up between aeronautics, education and other categories.

Griffin noted that the budget has broken down that way for four decades.

"That represents, if you will, a long-term consensus of what policymakers believe is the relative priority. And I think that's about right," he told msnbc.com during a July interview.

However, the line between the human spaceflight program and the space science program is getting fuzzier: The Hubble repair mission, for example, was added to the shuttle flight schedule after the public and lawmakers protested NASA's plans to just let the telescope fade away. This week, the mission was delayed until early next year, due to a new Hubble glitch that will require a fresh round of mission planning.

Ed Weiler, associate administrator for NASA's science mission directorate, said NASA's decision to send the space shuttle on a service call was a godsend. "This is one last gift from the space shuttle program to Hubble," Weiler told reporters last month at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

Synergy at work

Future manned missions will benefit from the techniques developed in cooperation with engineers at Goddard for fixing Hubble, said Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA's associate administrator for space operations. "That ability to repair in space is something that's going to be critical to us as we move forward in exploration," he told msnbc.com. "So we are really learning from the Hubble team on how to build these new tools, how to build these techniques to repair in place."

In fact, once the shuttle crew is finished with Hubble, the next visitor will likely be a robot. Shuttle spacewalkers will be attaching a soft-capture mechanism, built to hook up with a future robotic vehicle that could conceivably service the telescope (or direct it down to a controlled atmospheric re-entry if it's not worth saving). The robotic option was initially considered for the current round of repairs, but NASA decided to go ahead with a shuttle mission because retrofitted robotic technology ran a higher risk of failure.

That may change in the future, said E. Michael Kienlen Jr., deputy project manager for Goddard's HST Development Office. "We're clearly in the camp that an integration of the robotics program and the humans is the way to go," Kienlen told msnbc.com.

Gerstenmaier noted that the space station already has a two-handed, Canadian-built robot named Dextre that's designed to change out components and make repairs.

"We'll gain some real experience with space station on how effective that robotic servicing is, how well it works, how much it can be used — and then we can take that information and provide it back to our science community," he said. "They can go look at what we've done with station and see if ... we want to make robotic servicing more of a future [option] on some of the spacecraft. So again, I think we'll get a chance to see the synergy between the two programs."

Looking ahead

The human-plus-robot trend is popping up in a variety of settings: For example, NASA has been testing sensor-laden satellites the size of bowling balls that can fly in formation in zero-G — potentially serving as remote-controlled eyes and ears for autonomous tasks in space.

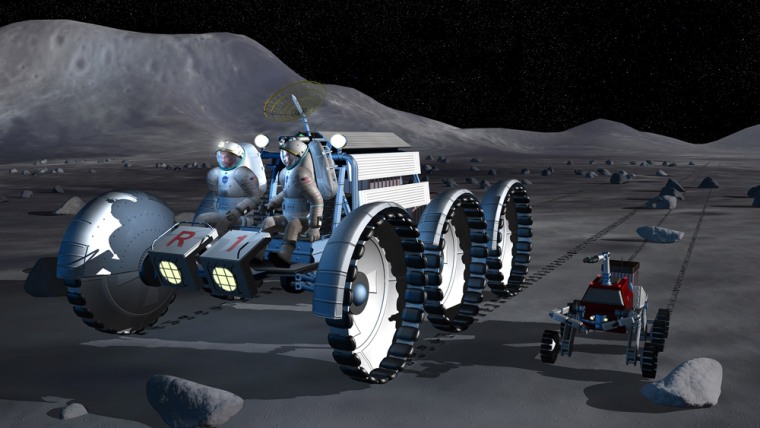

One project, involving engineers at NASA as well as at the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is aimed at developing a human-shaped robot dubbed Robonaut that could do the same types of tasks that human spacewalkers do. Another NASA team has created a six-legged robot known as Athlete that can step autonomously over moon rocks, carrying cargo or a crew cabin on its back.

This year, NASA demonstrated a robotic rover equipped with a drill designed to find water and oxygen-rich soil on the moon. Such machines could go prospecting for the sites most suitable for human settlement.

If NASA can develop robots to do all these tasks, are humans really necessary? Is manned spaceflight worth the greater risk and expense?

"It's just such an old-fashioned way to do things in this modern world," said physicist Robert Park, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland and a longtime critic of human space missions. He told msnbc.com that sending people into space was an outdated hangover from NASA's beginnings in the Cold War space race.

"We wouldn't be doing it now had it not been for the Russians," Park said.

Park's space heroes include NASA's Mars rovers, who have been on duty 24.66 hours a day on the Red Planet for coming up on five years straight, living solely on sunshine and never complaining. "That's where the future is," he said. "The future isn't in a spacesuit, for heaven's sake."

NASA's Griffin sees it differently, as you might expect. In his view, the drive to put people in outer space is the same drive that led early humans out of Africa hundreds of thousands of years ago, across the Bering Strait tens of thousands of years ago, and across the Atlantic in sailing ships hundreds of years ago. Robots can serve as trailblazers, or even sidekicks — but the future still belongs to the one wearing the spacesuit.

"The criticism of manned spaceflight seems to be solely that, well, it's not science," Griffin said. "You're right, it's not. Manned spaceflight is not science. Human spaceflight is about expanding the range of human action. And I think that matters."