Video games don’t often bring a tear to my eye. No, scratch that … now that I think about it, video games — unlike movies and books — have never brought a tear to my eye … not until this weekend, that is.

That’s because this weekend I played “Gravitation” — a seemingly simple game dressed up in the kind of 8-bit graphics made popular circa 1983 and a game that takes only about 10 minutes to play. Yes … 10 minutes. And yet, in those 10 minutes, it manages to speak volumes about the heartbreaking balancing act parents face in trying to raise a child while also trying to pursue their own ambitions.

And while I admit that my recent adventure into motherhood has taken the coal-black rock that was my heart and transformed it into a gelatinous mass of warm goo, still … there’s no denying that the thought, nuance and authentic human emotions squeezed into this game are nothing short of awe-inspiring.

And the ending … even those still in possession of a stone where their heart should be might find themselves wiping away a tear or two as “Gravitation” draws to a close.

“Gravitation” was created by Jason Rohrer, a father of two and a respected independent game designer. On Saturday, it was given the Jury Award at the IndieCade games festival underway this week at the Open Satellite gallery in Bellevue, Wash.

Aiming to be a Sundance Festival for independent games, IndieCade is the first standalone independent games festival (that is: it’s not a part of some larger games festival) and one that's meant to introduce the public at large to the joys of independent gaming.

And here, Rohrer’s game isn’t the only one mining some surprisingly deep emotional territory. From the awkward and sometimes comical feelings that arise during sex to the poignant experience of confronting childhood memories to the joyous and heart-wrenching juggling act that is fatherhood, a host of independent titles are busy proving that — despite much evidence to the contrary — video games really can explore and evoke the kind of emotional experiences that movies and books do.

“One critique of contemporary commercial games is that they have less emotional breadth than, say, novels or film,” says Celia Pearce, the festival chair. “Imagine if the majority of films that came out every year were action and horror films, which is exactly the situation we have currently in the mainstream game industry. Now, imagine that games had the breadth we are used to in film. Imagine a ‘love story’ game or a ‘coming of age’ game or a game about mortality, parenting or spiritual enlightenment. These are some of the themes tackled in games featured in IndieCade.”

Grown up games for grown-up gamers

Not surprisingly, the “Dark Room Sex Game” has been drawing some of the biggest crowds at IndieCade. As the name implies, it is a game about sex … in a dark room.

But Lau Korsgaard, one of the students from IT University of Copenhagen who created the rhythm game, insists: “We weren’t trying to simulate sex; we were trying to simulate some of the feelings around sex. We wanted to show that you could approach sex in a different way.”

Certainly it’s hard to find any sort of realistic sexual relationship represented in a mainstream video game. Instead, the sum of the human sexual experience tends to be expressed by underdressed female characters sportingand personalities as deep as rain puddles.

But the “Dark Room Sex Game” has no graphics whatsoever. Instead, this multiplayer computer game — played with Wii Remotes held in hand — asks players to rely completely on auditory cues and vibrations from said Remote.

Players take turns swinging and whipping their controller back and forth with their partner in the kind of carefully timed rhythm that can only be achieved by working together. The moans and wails of sexual congress tell players whether they’re moving too fast or too slow. The object of the game is to reach an “orgasm” before the competition does.

As titillating as it sounds, the game is really more interesting in the way it evokes the awkwardness of first sexual encounters and the challenge presented in finding the kind of give and take that makes for a successful relationship — sexual or otherwise.

Kid-friendly Nintendo certainly won’t be knocking on Korsgaard’s door anytime soon to snatch up this game for the Wii. But why not? The average gamer today is 35 years old.

“Our tastes have been maturing as we’re getting older, but games are lagging behind in terms of the kinds of topics they’re dealing with,” Rohrer says.

Rohrer certainly isn’t afraid to tackle mature topics. His previous game — “Passage” — took on the heady subjects of life and death and the choices we make in the time we have between the two. It was a topic that was on his mind as he turned 30 and as he dealt with the death of a close friend.

“Gravitation” — which can be seen at IndieCade throughout the week or can be downloaded for free from Rohrer’s Web site — is equally autobiographical, drawn from Rohrer’s experiences trying to be a good father to his young son Mez while also pursuing his artistic ambitions and inspirations.

(Spoiler Alert: Download and play this game before you read further.)

The game puts players in control of a father figure and begins by having you toss a ball back and forth with your child. The more you play with the child, the more your view of the game world expands and the higher you can jump. The higher you can jump, the farther away from your child and your home you can travel, acquiring more and more stars, which fall to earth as blocks of ice.

But spend too much time pursuing stars and you’ll return home to find your child blocked off by a wall of ice. Spend even more time away from home and you may return to find your child gone from you forever.

The metaphor is clear — we are inspired to pursue our ambitions by those we love most, and yet the pursuit of our ambitions can close us off from the very people who inspire and love us. (Cue tear rolling down cheek.)

The Sundance effect

But that’s not to say that all the games at IndieCade or that all independent games in general insist on taking players on deliberative journeys of great human import.

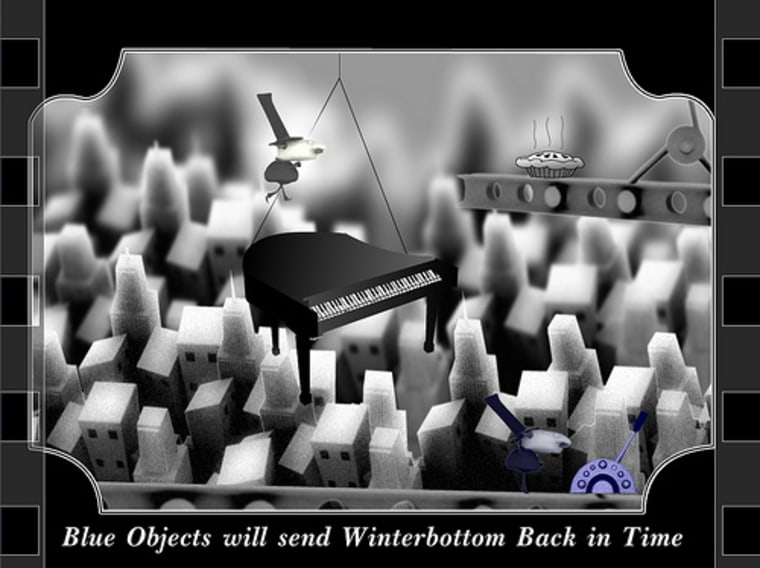

“The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom” — also on display at IndieCade — references the silent black-and-white films of yore and asks players to manipulate time as they help a mustachioed character pursue his love of nothing more important than pies.

Meanwhile, the gorgeous point-and-click adventure game “Machinarium” takes players to an entirely different universe, a place of rusty machinery and elaborate contraptions where players help a robot save his robot girlfriend and stop his robot enemies. (While you wait for the full game to launch, check out the developer’s excellent earlier work “Samarost 1” and “Samarost 2”).

“There’s something here that’s interesting to everybody,” says Stephanie Barish, the founder of IndieCade.

Barish hopes the festival will help bring independent games to mainstream audiences the way Sundance helped bring independent film to the mainstream.

Sam Roberts, the festival director, believes the general public would embrace independent games if they only knew they existed. In fact, he believes that non-gamers would probably be more open to independent games than longtime gamers — after all, they haven’t been hard-wired by a life spent playing games to think of them in a narrow way.

He also believes that the way independent games dare to tread into more expansive emotional territory will appeal to a broader audience.

“A film buff sees films that entertain, films that cause laughter, films that cause tears, films that educate and everything in between,” he says. “The same is true of the committed reader of literature or the passionate music fan. By expanding the possibilities of what a game can do, indie games better serve a general public that is interested in diversity in their media diet.”