In December, 1912, J. P. Morgan testified before Congress in the so-called Money Trust hearings. Asked to explain how he decided whether to make a loan or investment, he replied, “The first thing is character.” His questioner skeptically suggested that factors like collateral might be more important, but Morgan replied, “A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.”

Morgan’s point was simple but essential: systems of credit depend on trust. When trust is present, money flows smoothly from lenders to borrowers, allowing new enterprises to start, existing ones to expand, and daily business to move along without a hitch. When it’s absent, we find ourselves in a world where lenders hoard capital, borrowers are left empty-handed, and the economy’s gears grind to a halt — a world, in other words, like the one we’re now living in.

A few years ago, banks and other lenders seemed indifferent to risk, as they doled out loans to people with dubious incomes and poor credit records. Today, they are positively paranoid, distrusting even the best borrowers and forcing companies to pay far more interest on money borrowed. The interest rate on the most highly rated two-year corporate bonds has risen by fifty per cent in the past month, even as the interest rate on government bonds has fallen.

Shocking as the current stock-market drops have been, the freezing up of the flow of credit is far more damaging to the health of the U.S. economy. So, during the past few weeks, the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve have been desperately trying to fight that freeze. Scarcely a day goes by without some dramatic new initiative, even as market chaos makes each new idea soon seem like ancient history. (It’s been just over a week since the Treasury’s plan to buy seven hundred billion dollars’ worth of “toxic assets” became law, but already it feels like a year.)

Last week, in a potentially crucial move, the Fed announced that it would start buying billions of dollars in commercial paper — which means that it will be issuing short-term unsecured loans to corporations. The Fed has historically been the lender of last resort to banks. Now it’s becoming the lender of last resort to everyone.

Commercial paper is the name for short-term promissory notes that companies sell to raise money for daily operations, to meet payroll, and to bridge the gap between when they spend and when they get paid, while keeping their own cash in higher-yield investments. Commercial paper is not a new innovation — Goldman Sachs actually started as a commercial-paper firm, in the late nineteenth century — but it has become essential in day-to-day business in the U.S.

Since 1980, annual commercial-paper issuance has gone from $124 billion to $1.6 trillion. Most of these loans are unsecured — companies don’t put up collateral but simply promise to pay the loans back out of cash flow — so only well-established, financially solid companies can tap the commercial-paper market.

Because commercial-paper loans are short-term and are made only to companies with sterling credit ratings, they’ve always been assumed to be practically riskless, and lenders (most notably money-market funds) have been willing to lend at low interest rates. But the past year has called into question the very idea of a low-risk loan.

Lehman Brothers, after all, still had an A2 credit rating when it went under, taking down with it billions in commercial paper. Since its failure, lenders have adopted a gimlet-eyed approach to everyone, making it hard for key companies to perform basic transactions, and thereby exacerbating the market panic. A company like AT&T. is hardly likely to go bankrupt in the foreseeable future, but, after Lehman’s collapse, lenders were so skittish that AT&T couldn’t get commercial-paper loans that lasted longer than overnight.

The fear that has overpowered lenders is not just about the current market chaos. It also reflects their lack of faith in the models and systems that they rely on to evaluate risk. For Morgan, that process of evaluation was all about relationships. In the modern financial system, by contrast, risk evaluation involves two things: impersonality and outsourcing.

Personal judgments about the reliability of a borrower — the sort of judgment that Morgan, or a small-town banker, would make before issuing a loan — have been replaced by mathematical models. And lenders have delegated much of the responsibility for evaluating borrowers to other players, such as credit-rating agencies. In many cases, an AA rating was all a company needed to get a loan.

There’s no doubt that this system has had huge benefits. It has made it easier for money to connect lenders and borrowers. It has removed the kinds of personal bias that kept capital in the hands of people whom men like J. P. Morgan approved of. And it has vastly expanded the amount of lending as well. But all those benefits have come at an exorbitant price.

The problem with an impersonal system is that when the models fail, and when companies’ ratings become suspect, everything is called into question. Lenders can’t fall back on their own judgments of a specific company or individual, because such judgments aren’t part of their typical decision-making process.

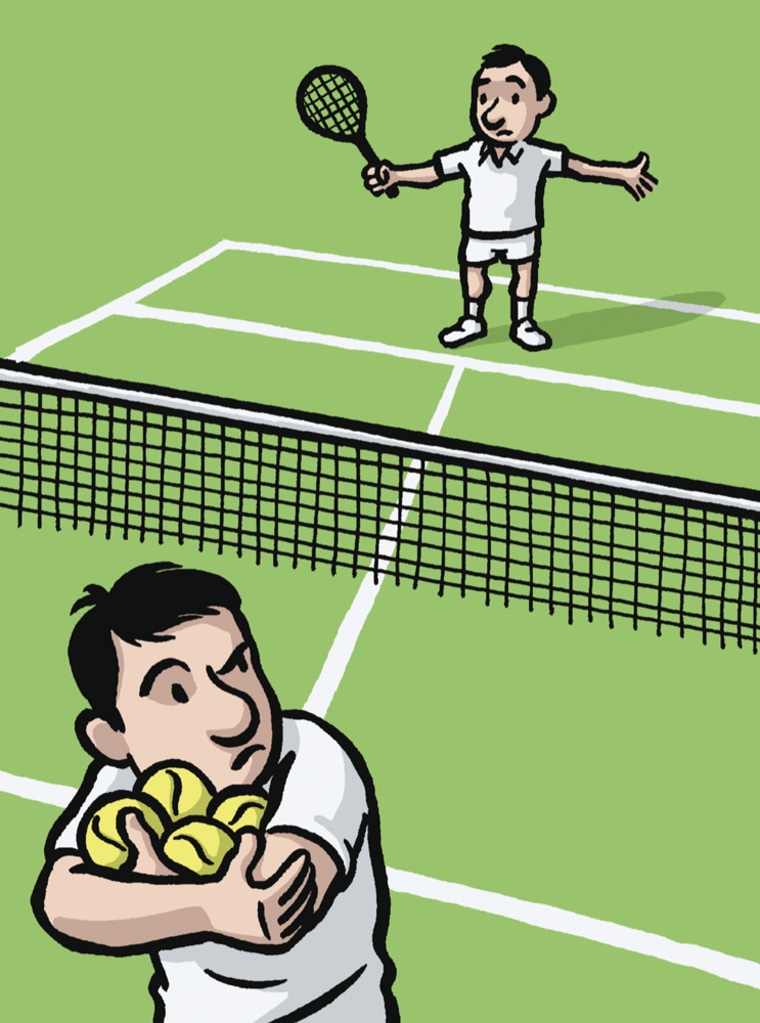

Instead, they’ve adopted a deep-seated distrust of all borrowers, even financially secure ones. If the Fed is now taking corporate I.O.U.s, it’s because everyone else is acting according to that old motto: In God we trust — all others pay cash.