I am sitting in a tiny changing room at a mammography center, shirtless, and I am crying. No reason to, logically: I haven’t even taken my test yet. Nor have I found a lump. At 35 years old, I know there’s little chance this screening will tell me I’m anything but perfectly healthy. “It’s a simple baseline mammogram, recommended for women with a family history of breast cancer,” my doctor had told me at a checkup, scribbling a referral to a radiology practice near my home in New York City.

When you’ve nursed someone you love through cancer, though, there’s no such thing as a simple screening. And when that person shared your genes, it’s doubly fraught. I pull a dusty-pink hospital gown from a pile in the changing room, wipe my tears on the sleeve and wonder, How many times did my mother go through this routine? And what did it feel like when it went wrong? I can’t imagine what ran through her mind between the appointment in July 1996 when the doctors found her cancer and the moment when she gathered my sister and me on the living room sofa, both of us in our 20s, and grasped our hands tightly. “I have bad, bad breast cancer,” she said, her voice breaking. She died a mere 13 months later, after being diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer, a rare and virulent form of the disease. She was three weeks from her 58th birthday.

My confession today is that it has taken me nearly two years from the time my doctor recommended a mammogram for me to actually get one. I delayed making an appointment for more than a year, the prescription sitting in a stack of junk mail. Months later, I arrived for the visit and discovered I had left the prescription at home. While I pondered my missing paperwork, an older woman next to me beseeched the desk clerk to check the book again for her apparently missing appointment. I quickly offered her my slot and scheduled another one five months down the road.

Now my reprieve is over.

I am well insured, well informed — I oversee the health coverage at SELF — and well aware of the lifesaving difference early detection can make. The only thing standing in my way has been a mix of scary emotions: fear of a poor result, denial of my above-average risk, dread of having to talk with strangers about what happened to my mother, sadness to be walking in her footsteps. It’s a toxic cocktail that has brought on my paralysis.

No good time to put off screening

For many women, a little anxiety is a helpful kick in the pants. Numerous studies show that the greater a woman’s perceived risk for breast, cervical and other cancers, the more likely she is to get tested for them. Some research, however, suggests that those who are most fearful may actually be the least likely to get screened, according to experts at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. You already know which camp I fall into. And there are a lot of us: women who by all rights should know better. According to a 2007 Harris Interactive survey for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Washington, D.C., one in five American women does not want to know if she has cancer. The number was a notch higher for those who had a family history. “For a subset of women, the fear is real and intense, and it can be disabling,” says psychiatrist Mary Jane Massie, M.D., director of the Barbara White Fishman Center for Psychological Counseling at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Breast Center in New York City. Physicians say younger women whose doctors recommend an early cancer screening may be more likely to fall into that anxious group because tests such as mammograms and colonoscopies are not yet a routine part of their medical care.

During the years I avoided my mammogram, I thought of my relative youth as a license to stall — growing older, I rationalized, is the highest risk factor for breast cancer. But because younger women often have faster growing, more aggressive tumors, early detection is critical for them. “If you are going to put off getting screened, when you are younger is certainly not the time to do it,” notes Mary Mahoney, M.D., director of breast imaging at the University of Cincinnati.

There is in fact no good time to put it off. Cancer caught through routine screenings tends to be at an earlier, highly treatable stage. When breast and skin cancers are found early, five-year survival rates reach 98 percent, reports the American Cancer Society in Atlanta. If the cancer has had time to spread to nearby organs or lymph nodes, however, the survival rate drops to 84 percent for breast tumors and to 65 percent for melanoma. “The type of patient that worries me is the one who knows she has cancer but sits at home until she has advanced disease,” Dr. Massie says. “It is a tragedy, and we certainly have seen women who very much know what’s happening in their body and can’t force themselves to get checked.”

More sophisticated tests and early-detection campaigns have helped increase screening rates and saved lives. Yet these developments also might give women the willies. “We are aware of breast cancer, and that’s great,” says Elizabeth A. Poynor, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist in New York City. “But because we hear about breast cancer daily, some women feel they are just waiting to get it.” Meanwhile, the move to digital mammography from film machines has created an adjustment period for radiologists and patients. “The resolution is so improved that we’re picking up more,” Dr. Mahoney says. Yes, tumors are being detected earlier, but more women with healthy breasts are also enduring nerve-racking follow-up tests.

Other patients, particularly those at high risk and those with younger, denser breast tissue, may be asked to undergo additional ultrasound or MRI screenings even if their mammograms are clean. And any time a woman gets a call to return to the doctor, alarm bells ring. “We can tell women that the vast majority of these [callbacks] turn out not to be anything of real importance,” Dr. Mahoney says. “That’s all well and good until it’s you. Women are understandably concerned because they know so much and know what the possibilities are.”

Genetic testing has added another layer of anxiety. A test for gene mutations linked to breast cancer is even more distressing than a mammogram. A negative result, which indicates you do not carry the mutation, doesn’t put you in the clear, and a positive result could mean a lifetime spent wondering if this is the day that turns into the worst day of your life. “Some women have significant anxiety from that, and if somebody is not going to act on the results, and if her quality of life is affected, then she shouldn’t undergo testing,” Dr. Poynor says.

Screening hang-ups

My mother’s cousin died of breast cancer in her 40s. No one is sure what my great-grandmother died of, but Mom suspected breast cancer. That’s not enough evidence to make my doctors recommend a gene test — and given how a mammogram terrifies me, I’m grateful. I’d like to think that if information about my family tree changed, I’d opt for genetic counseling. But how long do you think it would take me to follow up on that referral? Denial about the issue runs high, Dr. Massie says. Some women in her care who test positive have sought out family members to pass along what could be lifesaving information, only to have the door slammed in their face.

Doctors and researchers have devoted relatively little attention to helping women like me move past our screening hang-ups, yet doing so could effectively promote early detection. It turns out that psychosocial factors — what we’re afraid of, how we manage our emotions, the support we get from others — can have an effect on breast cancer screening behavior that is equal to that of income, education and age, according to an analysis of research by psychologists at Long Island University in Brooklyn, New York. “Knowledge alone is not enough — we know a lot of things are good for us and we still don’t do them. But if you tap into the psychological factors, you can spark real change,” says Nathan Consedine, Ph.D., research assistant professor in the psychology department at LIU.

More medical centers need to make tests as palatable as possible to patients, and some have already taken steps to do so. Doctors, nurses and technicians can play a key role by walking women through the process before it starts and telling them how equipment works — explaining, for instance, why compressing the breast (the source of the worrisome ow! factor) makes mammogram results so much more accurate. Shorter wait times for appointments and quick turnarounds on results mean patients aren’t left waiting and wondering. When the new breast-imaging center at the University of Cincinnati opened this year, even the decor, which includes a soft green color scheme, aimed to soothe anxious patients. “We tried to make it as spa-like as you can get in a hospital,” Dr. Mahoney says.

Primary care physicians also need to do more than rip off a referral slip for the test once a year; they should acknowledge to women that a screening might prompt anxiety even as they underscore its importance. If your doctor doesn’t take the time to ask, you need to volunteer how anxiety-provoking cancer tests are for you. “It’s important to have a good dialogue,” Dr. Poynor says. “Ask, ‘What can I expect? What if it’s positive? What if it’s negative?’”

Few of her patients who have skipped their tests are willing to fess up to the full reasons why, Dr. Poynor adds. And doctors are hard-pressed to guess, because our fears are so individual. Younger women without much sexual experience may find a Pap daunting, for example, whereas other women avoid mammograms out of fear of pain or embarrassment. Others’ greatest worry is being alone when they discover they have cancer, so they neglect self exams.

Talking to your doctor about your fears can help the two of you find the best way to cope. “If I know a patient is scared it will hurt, I can explain the process so she knows what to expect,” Consedine says. If you need more hand holding, get it literally: Schedule screenings with someone who can comfort you and keep you honest. “I work with women who arrange to have a mammogram done at lunch with a girlfriend,” Dr. Massie says. “Then they go out afterward and turn it into a pleasant experience.” If you can’t take someone along, focusing on your loved ones can motivate you to make — and keep — the appointment, she suggests. “I really look at it as an obligation. We are obligated to ourselves and to the people who love us to do this.”

Still…I know my mother had no love for doctors or for facing up to bad news. In her hospital room after her double mastectomy, the two of us unwillingly overheard a psychologist’s ham-fisted attempts to counsel my mother’s dying roommate. Mom looked me in the eye and made me swear that, if there came a time when she couldn’t speak for herself, I would never allow a therapist to try the same with her. (When the hospice sent someone to our house in her last days, I kept my promise.) She hid her illness from her 91-year-old mother for far too long, out of fear of breaking her heart and from denial that she didn’t have more time. Fear and denial: I am my mother’s daughter. But would she be proud of my following in these particular footsteps?

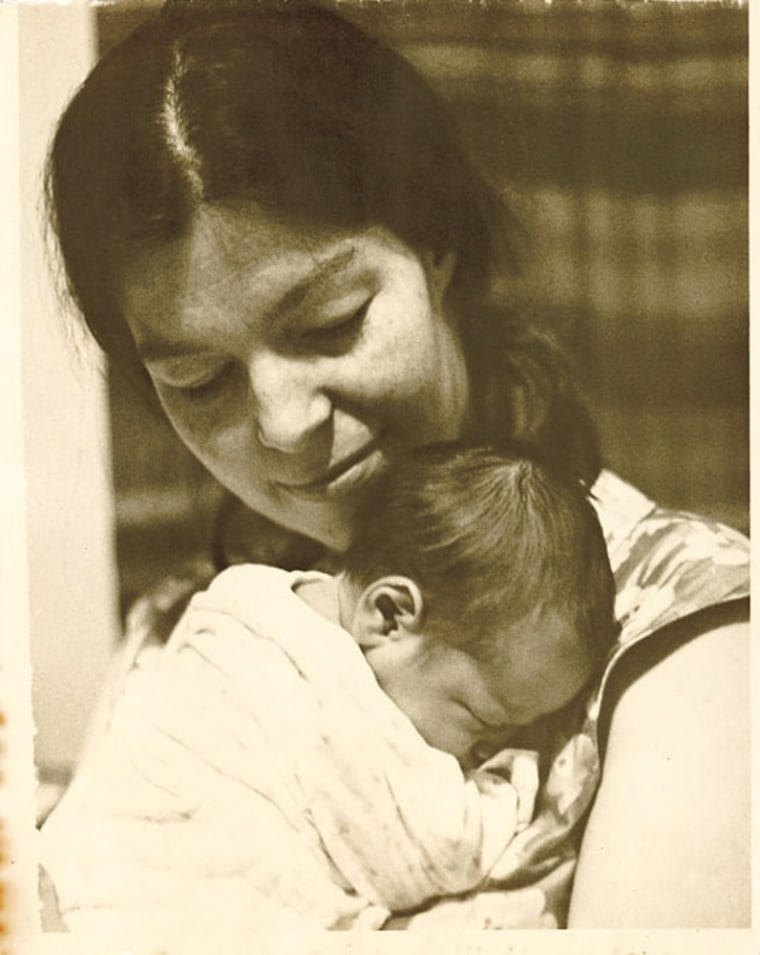

One day, my daughter will, like me, be forced at nearly every doctor’s appointment to confront her grandmother’s illness and her own higher risk. But I need her to know that fear of breast cancer is not my mother’s only legacy. She passed on a love of storytelling and the South. She taught me to value my vote and to hold those running the country accountable when they let us down. She loved reading and thrived in her job as a reference librarian. She taught me how to make a French braid and pecan pie.

Those are things worth living for, things I want to pass on. Certainly they are worth a few minutes of angst in a New York City screening center. I pull my hospital gown tight around me, gather myself and head out of the changing room. And I vow to actually change.