Fear overhangs a market where volatility seems to be the only thing that's a sure bet — witness this week's record one-day gain, followed by a big sell-off two days later, then a 400-point rally on Thursday.

But if the past is any indication, the pack mentality that tends to drive investor behavior at the extremes of any bull or bear market will eventually give way to more cautious analysis of whether stock prices are out of sync with corporate profits.

That's the backdrop as this week's initial batch of third-quarter earnings reports offers clues that could drive markets sharply higher or lower — along the lines of Monday's 11 percent jump in the Dow Jones industrial average, Wednesday's nearly 8 percent slide, and Thursday's nearly 5 percent climb.

Analysts and money managers agree that unusually sharp volatility and a freeze in credit markets have made it more difficult than ever to forecast a market bottom.

But many of them also say it's clear that stocks are a bargain at current prices, and poised to climb over the long run, even if they zigzag short-term. If third-quarter earnings end up coming in below Wall Street's expectations, some analysts still see room for stocks to gain.

"Any way you slice it, stocks will be either extremely cheap, or cheap, or just average," said Art Hogan, chief market strategist at Jefferies & Co.

Hogan is one of many who believe current prices more accurately reflect the broad market's true value than the five-year bull market that ended when the Dow hit a record high close of 14,164 points on Oct. 9, 2007. However, there's also a belief that the market has fallen too far with the Dow now trading below 9,000 points — a level not seen since 2003.

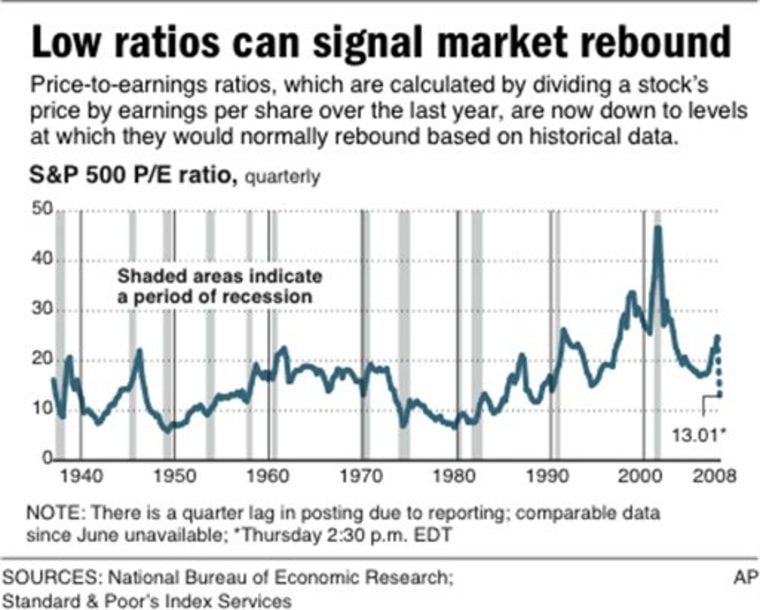

Their assessment is based primarily on historically low price-to-earnings ratios — a commonly used tool to determine whether stocks are fairly priced.

A P/E ratio is calculated by dividing a stock's price by a company's earnings per share over the prior 12 months. For instance, if a company's stock is trading at $75 and the company earned $5 a share over the last year, it has a P/E ratio of 15. If last week the company's stock fell to $60, the P/E ratio would have dropped to 12.

Historically the S&P 500 stock index trades with an average P/E ratio of 15 to 16, considered a benchmark for determining whether a stock is fairly valued. After last week's big sell-off depressed share prices, the S&P 500's P/E ratio sank to about 13. It nearly hit 14 after Thursday's market rally, but still hovered in territory not seen since 1989.

But what did valuations look like back in October 2007 when the Dow topped 14,000? Even as subprime mortgage troubles were beginning to ripple through the economy, the S&P 500's P/E ratio was above its historical average, and stood at about 19. By March it climbed above 21.

Still, that reflection of investor optimism was mild compared with late 2001, when the ratio topped 46 just before the bust in technology stocks began.

Some analysts who argue the market has come down too far from its October peak cite Exxon Mobil Corp. as an example. After the stock jumped 11 percent to close at $69.45 on Thursday, its P/E ratio rose to 8.6. Although the worsening economy is expected to reduce future earnings, Exxon Mobil's ratio remains unusually low, making the stock a relative bargain compared with where it stood several months ago. In the spring, Exxon Mobil's ratio rose above 13, and shares briefly traded above $96 as oil prices started to climb.

"As is always the case in a bear market, we will have overcorrected, and we will rebound from an overcorrected market," said Hogan, the Jefferies & Co. strategist.

If third-quarter earnings come in worse that analysts' recently lowered expectations, P/E ratios would head back up, undercutting the argument that stocks are undervalued.

But some argue the market has already fallen below any rational level. Hersh Cohen, chief investment officer for ClearBridge Advisors, said last week's unprecedented 18 percent drop seemed to suggest investors believed the global financial system was verging on collapse. Cohen believes global finances aren't that shaky.

"I thought we were in a complete panic phase," said Cohen, manager of the Legg Mason Partners Appreciation Fund. He said "it was psychology" that drove investors to sell beyond what rationally may have been warranted.

Indeed, part of the irrationality of stock pricing is evident in instances where stock prices fail to reflect the cash and other assets companies have on their books. Among the nearly 9,200 stocks tracked by S&P's Compustat Research, nearly 10 percent were trading below the value of their per-share cash holdings last week.

"A company at the very least has to be worth the cash it has in hand, doesn't it?" said Robert Froehlich, chief investments strategist with DWS Investments, the retail arm of Deutsche Bank's asset management division.

The market's recent defiance of such norms demonstrates that traditional valuation measures can't account for certain peculiarities. For example, firms with sound balance sheets that are in normally recession-proof industries, such as energy and health care, are finding their growth prospects and even daily operations crimped by frozen credit markets.

"The best investments will probably be the firms which are least vulnerable to continued problems in the credit markets," said Jim Cataldo, an assistant professor at Suffolk University in Boston who teaches accounting valuation. "Nearly any company will look good now from a price/earnings standpoint."

And then there's the role investor psychology plays in triggering sales of stocks. Investors pulled out nearly $56 billion from stock mutual funds during the first 10 days in October, the largest such outflow since such record-keeping began in 1984, according to TrimTabs Investment Research.

"There's always a risk your investors will panic, forcing you to sell at the very time you wish you could be buying," said John Dorfman, portfolio manager of the Dorfman Value Fund.

Dorfman has kept about 8 percent of his fund's $11 million in assets in cash. Now, he hopes to use much of the cash to snap up stocks he thinks are undervalued. He plans to buy before the Nov. 4 presidential election, when he expects investors too jittery to take the continued volatility will have exited the market and positioned it for a sustained rebound.

"I think once the people who can't stand the heat get out of the kitchen, then the panic selling will abate," he said. "I feel like we are within a couple weeks of the capitulation being complete, although it might seem like two years."