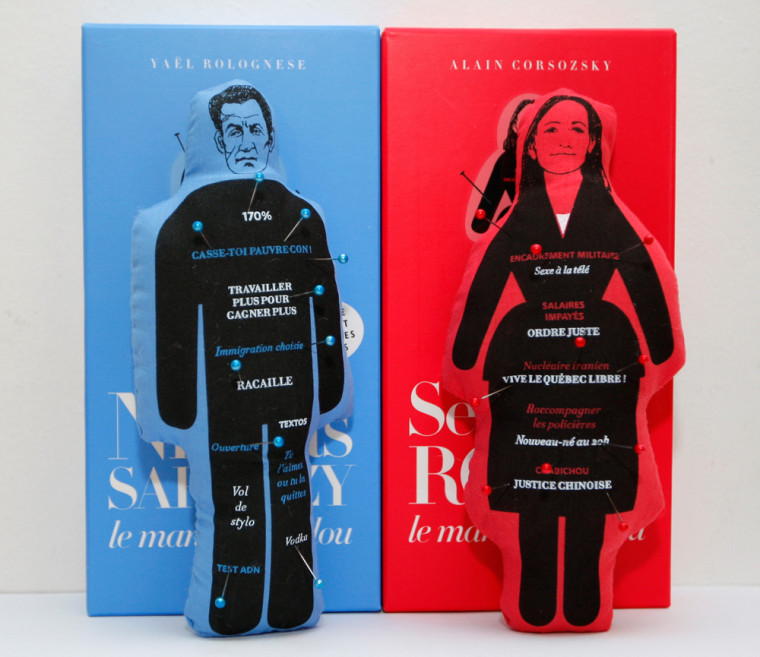

A controversial voodoo doll is proving to be quite the pain in the side of French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

The doll, which features Sarkozy's likeness and is being sold in some French stores, comes with a set of pins and an instruction manual on how to inflict voodoo curses on him.

Sarzoky is now suing the producer of the doll, which he says is an affront to his reputation and a misuse of his personal image.

It is unlikely that the publisher or Sarkozy have thought much about voodoo's ancient roots during the doll fiasco, but the practice is in fact just one insignificant part of a complex belief system that makes up the mysterious religion, which is still practiced in many parts of Africa, Haiti, Jamaica and Louisiana, among others.

Vodoun, as the official religion is called by most of its practitioners, has little to do with the black magic, as its detractors suggest.

It does, however, have a lot to do with zombies.

The precise beginnings of voodoo are unknown, but the West African country of Benin is considered the birthplace of the religion, most historians agree.

Voodoo means "spirit" in the local language, and probably evolved there from ancient traditions of animism, or the belief that otherworldly spirits can inhabit the body of humans and animals.

Relationships with spirits is the central tenet of voodoo, whose followers believe in one supreme God in addition to a number of spirits representing the deceased soul of a once-living person.

Anyone can become possessed by spirits, who offer help to the living in the form of good fortune and protection from evil, according to voodoo myths. Voodoo priests guide the interaction between the living and the dead, and can call upon certain spirits depending on the community's need, it is believed.

While voodoo continued relatively unabated in West Africa — it is still an official religion in Benin with more than 4 million followers there alone — it left African shores in the 17th century with the slave trade.

Once spread throughout the Caribbean, the southeastern United States and parts of South America, displaced Africans felt a common thread through voodoo, though the religion morphed to include elements of Christianity to appease Catholic slaveholders.

Voodoo thrived most potently in Haiti, where it remains a common belief system to residents while shrouded in mystery to outsiders.

It's that mysterious element of the religion that allows black magic myths such as the use of voodoo dolls to proliferate in popular culture, experts say.

In actuality, voodoo dolls were unheard of or very rare in Africa and Haiti, and had only a small surge in popularity when voodoo migrated from Haiti to New Orleans in the early 1900s. Even then, the dolls were often used for benevolent purposes, such as helping an infertile couple conceive. The concept of pinpricking-for-pain style voodoo dolls is mostly a product of Hollywood.

Something that has been found to exist in voodoo culture, however, is zombies, according to research done in Haiti by anthropologist Wade Davis in the 1980s.

Most Haitians believe that a dead person can be revived as a zombie, even after burial, Davis found, though few had ever admitted to seeing the real thing.

Investigating further, Davis uncovered several cases of individuals who had been put into a trance-like zombie state not by some magical incantation, but by a powerful poison administered by a voodoo priest. The poison, which contained toxins drawn from the Japanese puffer fish, can make its victim appear dead for several days, leading many victims to be buried alive before "awakening" in a zombie-like haze.

Getting "zombified" is sometimes used secretly as a punishment for doing wrong within the community, Davis said.