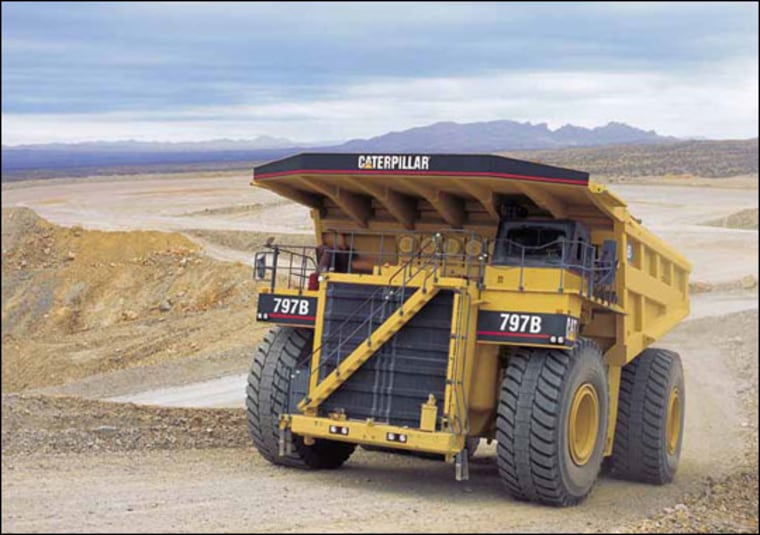

The largest truck in the world is about to become the largest robotic vehicle in the world. Computer scientists from Carnegie Mellon University have teamed up with engineers from Caterpillar to automate the 700-ton trucks, which are made to haul loads up to 240 tons from mines.

That's nearly two million pounds of metal, fuel and stone powered by a 3,550-horsepower, 24-valve engine moving at up to 42 miles per hour, with software and a robot at the wheel.

"Autonomous vehicle technology is pretty much in its infancy," said Tony Stentz, a professor at CMU involved in the project. Stentz expects that over the next five to 10 years, the technology will expand to areas beyond mining, eventually finding its way into consumer cars and trucks.

Catepillar's soon-to-be-automated hauling trucks will be the largest but not the first. Caterpillar's rival, Japan-based Komatsu, already runs automated trucks at the Gaby mine in Chile. Rio Tinto, a British/Australian mining company, recently announced plans to fully automate its Pilbara iron ore mines in Australia, including its Komatsu trucks, by this November.

The Caterpillar trucks will be equipped with numerous high-tech gadgets and software to keep them on the road. GPS receivers would continuously monitor the location and direction of the trucks.

Laser range finders would sweep the road in front of the trucks to identify large objects. Video equipment would then determine if the object is a hazard, such as a rock, or not. All of the information would then be run through a computer program that would tell the robotic driver to avoid the obstacle or not and by how much.

The software to run the trucks will be adapted from CMU's part in the DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) Urban Challenge, a competition that required unmanned vehicles equipped with sensors and artificial intelligence systems to navigate through an urban environment filled with obstacles. The software will require some changes to adapt to mines, Stentz said, but he wouldn't elaborate on the details.

Fully automated mining trucks promise to reduce maintenance costs while increasing productivity. While being careful not to say what Caterpillar's performance expectations will be, Stentz offered a "very rough calculation" that by running at peak capacity 24 hours a day, seven days a week, the trucks could be up to 100 percent more productive.

Mines are also dangerous, and removing humans from dangerous jobs will help save lives, said Mark Campbell, another DARPA Urban Challenge participant from Cornell University.

"I personally think this is a good idea," said Campbell. "The safety of miners will be greatly improved because of the lighting issues, fog, dust and other conditions that make driving around a mine difficult."

While mines have tough conditions, they are much easier to navigate compared to the urban areas both Cornell and CMU faced in the Urban Challenge.

Fully automated consumer vehicles aren't likely to arrive any time soon. Bits and pieces of the technology, like self-parking cars and backup warning systems, already exist. More devices will be added as costs come down, the sensors become better refined, and drivers come to rely on them more.

But drivers are still needed, at least for now, says Campbell: "The sensors would give the driver more information, so the human operators are still in charge or at least in control."