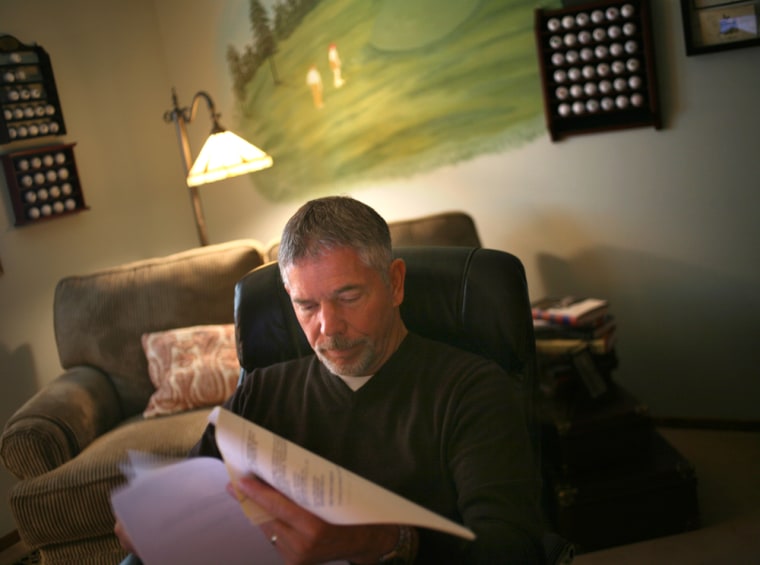

When Gary Laursen began working in the transportation industry four decades ago, he had a pretty good idea of what it would take to retire comfortably.

The 62-year-old former account executive for a trucking company, who lives with his wife in Spokane, Wash., says he began setting aside a piece of each paycheck the day he started working. His careful planning paid off. After retiring two years ago, he played golf, spent more time with his three grown children and grandchildren and had enough socked away to pay the bills.

“I felt like I had plenty to retire,” he said. “We’re not a wealthy family by any chance. We’ve lived a very nice life, and our home is paid for and we don’t owe anybody any money.”

But as the financial markets have ravaged retirees’ savings and investments, Laursen has put his retirement on hold. On top of a big hit to his retirement savings, his former employer just eliminated health care coverage for Laursen and his wife. So he’s gone back to work as a consultant, helping former clients with shipping logistics.

“I either make more money doing what I’m doing and work longer, or I spend everything I’ve got and let the system take care of me later, which I don’t like,” he said.

And with the economy and financial markets showing little sign of hitting bottom, it’s not at all clear when — or whether — Laursen will be able to return to the retired life he worked 40 years to build.

“I’m 62,” he said. “I don’t have time to build it back up. So I’m stuck.”

Millions of Americans are confronting the same stark reality after the collapse of the stock market destroyed trillions of dollars of retirement savings and forced those in or near retirement to make serious adjustments to their plans. For some, that has meant abandoning the idea of retirement altogether.

Jeanne Pecora, a single, 63-year-old paralegal in Virginia Beach, Va., is still working. But she’s already having trouble making ends meet — let alone setting aside more money to rebuild her battered retirement nest egg, which she says lost 70 percent of its value in the past three months.

Her 6-year-old car spends more time in the repair shop these days. To cut costs, she’s cut back on eating out for lunch or dinner by making meals at home that she can stretch for two or three days with leftovers. She’s switched to cheaper Internet and cellphone services, and cut back on snacks for her two dogs.

“I plan to keep working until I’m 70 if I’m still in good health, and if no one pulls the plug on older employees,” she said. “But I do not know what will happen if or when my health fails.”

For the millions of newly retired and nearly retired, the financial market collapse couldn’t have come at a worse time. Those who have watched their savings evaporate now face stark choices: either cut back spending or put off retirement — or both.

Even before the market downturn picked up speed in September, some one in five people had put off retirement, according to a survey by AARP. More than six in 10 workers 45 and older said they were delaying retirement and expected to work longer; nearly seven in 10 said they’ll spend less once they reach retirement; according to the survey. About a quarter said they’re putting in more hours at work to try to make ends meet.

“Their standard of living has been lowered,” said David Certner, legislative policy director for AARP. “They’re cutting back on their vacations and the number of times they’re going out to dinner, and other travel and entertainment and is lower. So they’re in a tough spot.”

Though the recent economic turmoil has thrown the problem into sharper focus, older workers have been losing ground to a secure retirement for several decades. During that period, American employers — with the help of changes in the law and tax subsidies encouraging private retirement savings — have shifted the burden of saving and managing investments to individual workers.

But as companies turned away from providing traditional pension plans that paid a “defined benefit” for life — typically a monthly check — the growth in coverage by individual plans hasn't kept up. Since 1992, there has been an overall drop in all retirement coverage, according to a 2006 paper by Stephanie Costo, an economist with the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That drop in retirement coverage has been matched by a rise in the number of older workers who remained in the work force later in life for a variety of reasons. It’s not clear whether people are working longer because they want to or because they have to. But after a steady decline, the retirement age has been rising over the past few decades.

In 1985, some 15 percent of men and fewer than 8 percent of women remained in the workforce after age 65, according to a paper by Georgetown University demographics professor Murray Gendell. By last year, 34 percent of men and 26 percent of women had a job or were looking for work. The same pattern holds for workers 70 and older.

Employers offering traditional defined-benefit plans also have moved to shift risk to their employees by expanding the option of lump-sum payments — which removes the cost of retiree benefits from their books. In 1992, only 13 percent of employers offered lump-sum payment options; by 2005 nearly half of employers were doing so.

But while many older workers who had expected to retire now find they need to keep earning a paycheck to survive, it’s getting harder to do so. The national unemployment rate jumped to 6.5 percent last month from 4.8 percent a year ago. The rate is lower among older workers, but joblessness is rising among every age group.

Retirees have suffered through market downturns before. The conventional wisdom from most financial retirement advisors was that investing in stocks would help offset the corrosive impact of inflation on fixed-income savings like bonds. Like many retirees, Pecora, the paralegal, avoided selling her stocks because past market downturns have eventually reversed course.

“The last time (my retirement fund) fell that far was on Sept. 11, 2001, but I eventually got it all back by September 2007,” she said. “Now it's gone again.”

Given the scope and breadth of the turmoil in the global financial markets, it’s not at all clear how long it will take for investors like Pecora to recoup their savings.

That’s why financial advisers have long recommended a gradual investment shift, in the decade or so before you plan to retire, moving money out of riskier stocks into safer investments like money markets or bonds.

Investment firms catering to small investors have developed specialized "life cycle" funds, tailored to age and expected retirement date, that gradually shift assets to avoid the risk that stock holdings will plummet shortly before a planned retirement date.

But the traditional advice became more difficult to follow in the past decade. Historically low interest rates meant that returns on safer, fixed-income investments have barely kept up with inflation, and in some cases have fallen behind. So many older investors accepted more risk in the stock market.

“With some of the low returns on bonds, it’s not as if people had a lot good options,” said Certner.

Certner says some retirees are also finding out the hard way the dangers of investing too much of their 401(k) savings in their own company’s stock. When their employer hits hard times, they face a double risk: Their company stock may go down sharply just at the moment when they are facing a layoff. (Certner and many financial advisers recommend that employees keep no more than 10 percent of their savings in their own company's stock.)

It remains to be seen whether the current collapse of millions of individual retirement plans prompts changes in the government-subsidized, individual retirement system that has become the primary safety net for most Americans. Among the proposals under consideration are moves to increase participation by making individual retirement plans “automatic” and to provide incentives or requirements that expand the number of employers who offer company-sponsored plans and make contributions.

But the problem didn’t arise overnight, and it won’t be solved quickly. In the meantime, those who are near or in retirement have been left to cope as best they can until the economy and financial system can get back on its feet.

“It’s been a nice ride,” said Laursen. “But I think we all knew that something was going to happen eventually.

Like many msnbc.com readers, Laursen admits to some resentment that, having played by the rules and managed his money wisely, he’s caught in a predicament that wasn’t of his own making.

“I am very upset that I managed my money, bought only what I could afford, only to be penalized for making wise choices,” he said. “While others bought when they should not have, spent well above their income and now get bailed out, I am left wondering about survival.”

More on health insurance | pension