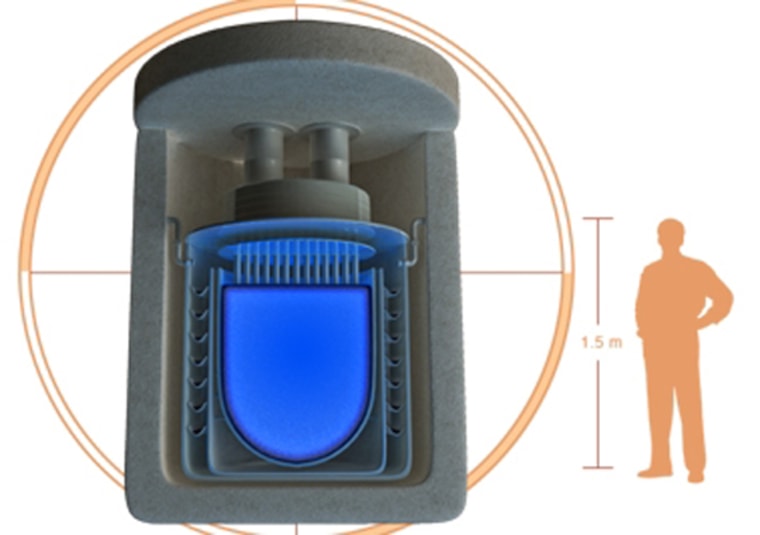

It's the size of a shed, but you're not likely to find it in any backyard.

Using technology originally developed by scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, Hyperion Power Generation is creating mini nuclear fission reactors that will provide electricity and hot water to remote locations, nearly all outside the United States.

"There is a strong humanitarian bent to these reactors," said John "Grizz" Deal, Hyperion's CEO. "This was invented to provide electricity and hot water to remote locations, where people might not have electricity or clean water."

Deal says that Hyperion has already received more than 100 orders for the $25-30 millions reactors, which are sealed shut with concrete and have no moving parts. The reactors are designed to generate electricity or boil water clean after being hooked up to water piped near their 500-degree surfaces.

Standard nuclear fission will generate the heat. As the uranium inside the reactor breaks apart naturally, it creates heat and sends neutrons (tiny particles that exist in the nucleus of atoms) blasting out. If those neutrons hit other uranium atoms they break apart as well, creating even more heat and more new neutrons.

Many modern nuclear facilities moderate the reaction with control rods that, when inserted into the nuclear fuel, slow down neutrons. But control rods can fail and reactors can overheat if not properly managed. Hyperion eschews control rods by adding hydrogen atoms to the uranium, which take the place of the control rods to moderate the reaction.

"Since the fuel and the moderator coexist in equilibrium, it's impossible for the chain reaction to go faster than we want it to," said Deal. "What we've done is essentially turned uranium hydride into a battery."

It's a battery you wouldn't want to touch. Using propriety technology, Deal says that they can transfer over 99 percent of the 500 degrees produced inside the reactors to the surface of the sealed concrete container. Whoever buys the reactor will pipe water past the those 500-degree thermal conductors, boiling the water to purify it or produce steam that would power nearby generators.

The high surface temperature, along with the fact that the reactors would be installed deep underground and at facilities that already have good security, should also prevent theft, says Deal.

Max Carbon, author of the book "Nuclear Power: Villain or Victim," and a professor of nuclear engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, agrees that the security risk of Hyperion's reactor is minimal.

"This is low-enrichment uranium, which is not useful for making a bomb," said Carbon. "If terrorists wanted to get radioactive material they could get it elsewhere much easier."

The concrete-sealed reactors may be safe from meltdowns, but they're not that effecient. Deal expects that power utilities can produce electricity for 20,000 homes for about ten cents per kilowatt hour for a minimum of eight years. That's about five times more expensive than electricity currently produced in the United States, which is one reason why these reactors will most likely not be found in this country.

Nonetheless, Deal argues that's still a good amount of power, especially for an area that had little or none before. Even better is that each plant leaves behind a minimum of waste.

"The waste from same amount of power generated from coal would fill ten football stadiums," said Deal. "We are making a football-sized piece of waste instead."

To Carbon, the numbers sound right; a bit expensive, but if there is no other source for electricity, then worth it. And Hyperion isn't the only company looking to produce small nuclear power plants. Toshiba has been working on the technology for years as well.

"I could see where there would be a great demand for these reactors from around the world," said Carbon. "But I won't get too excited until I start seeing dollar signs."

Those signs could come within five years. Hyperion already has a six-year waiting list for the reactors. The first reactor will likely be delivered to a Czech company called TES and installed in Romania.