A Florida man's quest to find hundreds of U.S. Marines buried anonymously after one of World War II's bloodiest battles could lead to the largest identification of American war dead in history.

Researchers used ground-penetrating radar, tediously reviewed thousands of military documents and interviewed hundreds of others to find 139 graves. There, they say, lie the remains of men who died 65 years ago out in the Pacific Ocean on Tarawa Atoll.

Mark Noah of Marathon, Fla., raised money for the expedition through his nonprofit, History Flight, by selling vintage military aircraft rides at air shows. He hopes the government will investigate further after research is given to the U.S. Defense Department in January — and he hopes the remains are identified and eventually returned to the men's families.

"There will have to be convincing evidence before we mount an excavation of any spot that could yield remains," said Larry Greer, spokesman for the Pentagon's Prisoner of War and Missing in Action Office.

U.S. government archaeologists would likely excavate a small test site first, he said.

Major amphibious assault

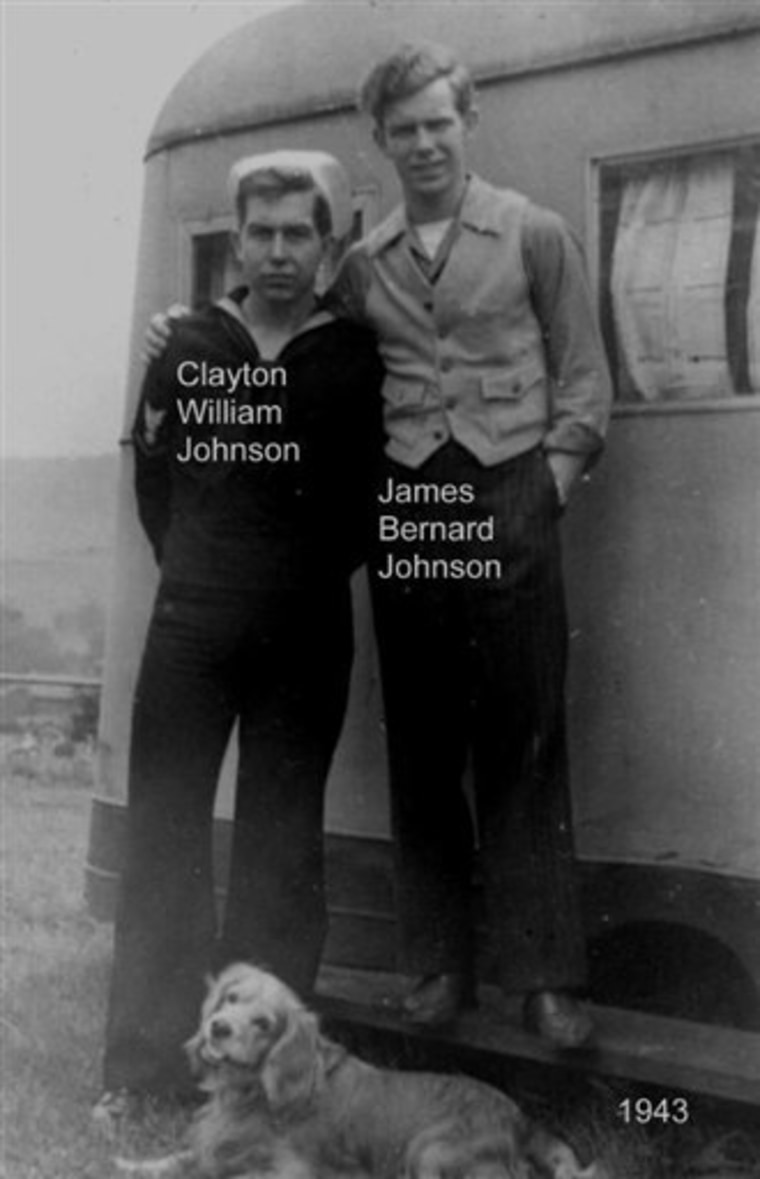

James Clayton Johnson never met his uncle, James Bernard Johnson, who died on Tarawa at age 17. But Johnson, who was named for his father's brother, never forgot that young Marine.

Now 60 and living near Noah in the Florida Keys, Johnson learned of the effort to identify the burial sites of his uncle and 541 other missing U.S. Marines on Tarawa while researching his uncle's military records online.

More than 990 U.S. marines and 680 sailors died and almost 2,300 were wounded in the three-day battle, one of the first major amphibious assaults in the Pacific.

Johnson, himself a veteran who led special forces troops into Cambodia as a 21-year-old Army platoon leader during the Vietnam War, isn't sure having his uncle's body returned to the U.S. would provide any sort of closure.

"There aren't any open wounds for me that need fixing," he said.

But Johnson wants the world to know about the volunteers committed to preserving the names and stories of thousands of American soldiers.

"My problem is that people don't care," he said. "I get pumped up, and I want people to think and look at things like this."

$90,000 raised

Noah, a 43-year-old commercial pilot and longtime World War II history buff, raised the $90,000 for the Tarawa work by selling rides at air shows and partnering with The American Legion, VFW and other groups.

Noah and Massachusetts historian Ted Darcy of WFI Research Group reviewed eight burial sites they believe contain U.S. remains. They say the claim is backed by burial rosters, casualty cards and combat reports; interviews with construction contractors who found human remains at the sites and locals who have found American artifacts; and other information.

But they'll leave the digging to the U.S. government, so the archaeological integrity of the sites isn't spoiled.

The names of many fallen soldiers were lost as U.S. Navy crews rushed to build desperately needed landing strips on the tiny atoll after the Nov. 20, 1943, invasion. Many of the graves were relocated.

The military didn't focus on identifying the soldiers who died at Tarawa until 1945, when an Army officer was tasked with unraveling the hasty reburials.

"You could sense his frustrations in his reports," said Noah, who reviewed all the burial records.

The brief telegram James Hildebrand's grandmother received on Dec. 26, 1943, said her 20-year-old son died on Tarawa Atoll and included this line: "On account of existing conditions the body if recovered cannot be returned at present. If further details are received you will be informed."

James Hildebrand, now 65 and living in Gilroy, Calif., said his grandmother wrote letters to the Navy for years trying to recover his uncle's body.

He'd like to know whether the remains could be buried in a mass grave in a military cemetery in Hawaii with a group of unidentified U.S. soldiers taken from Tarawa many years ago. And he hopes the Defense Department will try to find his uncle's body on Tarawa.

"If he's still on the island ... there's space in our family plot in Tucson where he could be buried. It would mean a lot to our family," he said.

For 10 years, Merill Redman of Illinois has ultimately been encouraged by reports of efforts to find his brother's body on Tarawa. He's been disappointed each time.

Redman, now 79, was 14 when his older brother joined the Marine Corps and left their small town of Watseka. He's even traveled to Tarawa himself, trying to find his brother and bring him home.

"Each little thread," he said, "it drives me on in this project."