One of the most dangerous faults in the world is primed for another monster earthquake, according to new research.

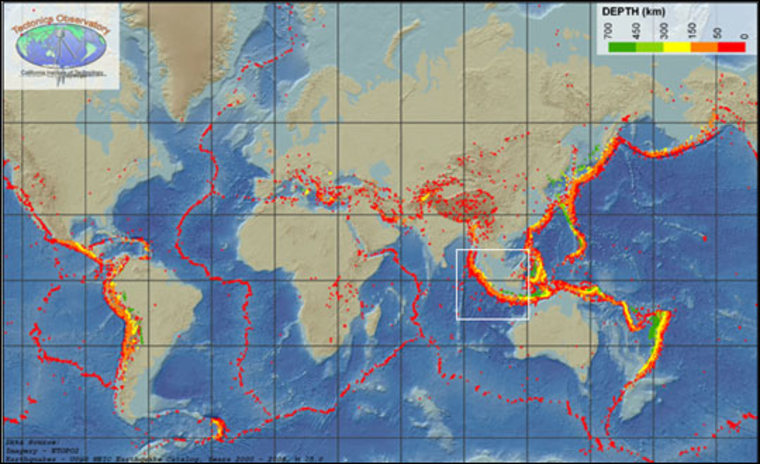

Situated off the west coast of Java in Indonesia, the Sumatra fault has been home to some of the most powerful earthquakes the world has ever seen. In 2004, a magnitude 9.1 quake caused a tsunami that devastated shorelines across the Indian Ocean, claiming close to a quarter million lives. In March of 2005 another quake struck, this time 8.7. In September 2007, two more, 8.4 and 7.9, hit within 12 hours of one another.

But Jean-Philippe Avouac of the California Institute of Technology and a team of researchers say the fault is far from done. In fact, last year's temblors only unleashed about 25 percent of the tension built up along the southern Mentawai section of the fault.

"We could potentially have another quake larger than 8.5 tomorrow," Avouac said. "Or we might have to wait a few decades, but the energy is available now."

Before 2004, the last two powerful quakes shook the Mentawai area to the tune of magnitude 8.8 in 1797 and between 8.9 and 9.1 in 1833. Because the scale used to measure earthquake strength is logarithmic, this means the older quakes were about 10 times more powerful than the 2007 tremors.

Why didn't Mentawai release all of its fury? Variations in temperature along the fault, how much water is in the crust, and even what rocks are grinding past each other can all play a role in determining whether rocks break violently or creep placidly past one another for centuries.

In the 2007 quakes, the ground broke in fits and starts, rather than cascading into one massive tremor.

"They broke in an uncoordinated way," Avouac said.

Areas that had been locked ruptured, unleashing huge amounts of energy. But they were separated in places where creeping rocks kept stress at a minimum.

"This is all part of chasing down what makes earthquakes start and stop," said Thomas Parsons of the United States Geological Survey in Menlo Park, Calif. As scientists seek to improve earthquake forecasting, he explained, it's vitally important to understand their cycles.

"As you try to calculate the probability of the next big quake, there's a lot of debate on how to do that," he added. "This study starts to hone in on the variability in magnitude you can get in the same section of fault."

While more detailed study will be needed, Parsons said that patterns in large earthquake occurrence may start to emerge, helping scientists predict when the next monster quake may strike.

For now, Avouac thinks enough energy is still stored in the fault to unleash a devastating quake — followed by a lethal tsunami — any moment.

"Nearby is the city of Padang, with a population of one million, living at low elevation," Avouac said. "So the tsunami threat is very high here."