This is a presidential city. In fact, every president since John Adams has called Washington home.

Each day, tourists visit the places these men ate and slept, worked and worshipped, looking for insight into their lives.

Adams, Lincoln, Wilson — they’re all here in spirit. Their echoes and artifacts are around every corner.

Soon, Barack Obama’s footprints will be included on the tour. His visit to Ben’s Chili Bowl on U Street or his stay at the Hay-Adams Hotel will be discussed on double-decker sightseeing buses for years come.

But before he can gather too many map points, here’s a look at the places made famous by his predecessors — a presidential tour of Washington, courtesy of msnbc.com.

Adam’s Potomac

We begin at the Potomac River, just south of the White House, near the Tidal Basin and the Jefferson Memorial. At this very spot, John Quincy Adams, our sixth president (and the son of our second), went for his swims in the summer of 1825.

In fact, on June 2 of that year, Adams recorded in his diary that he “swam fifty minutes against the tide” in the river. It was a little lonelier on those river banks back then — construction of the memorial didn’t begin for another 164 years.

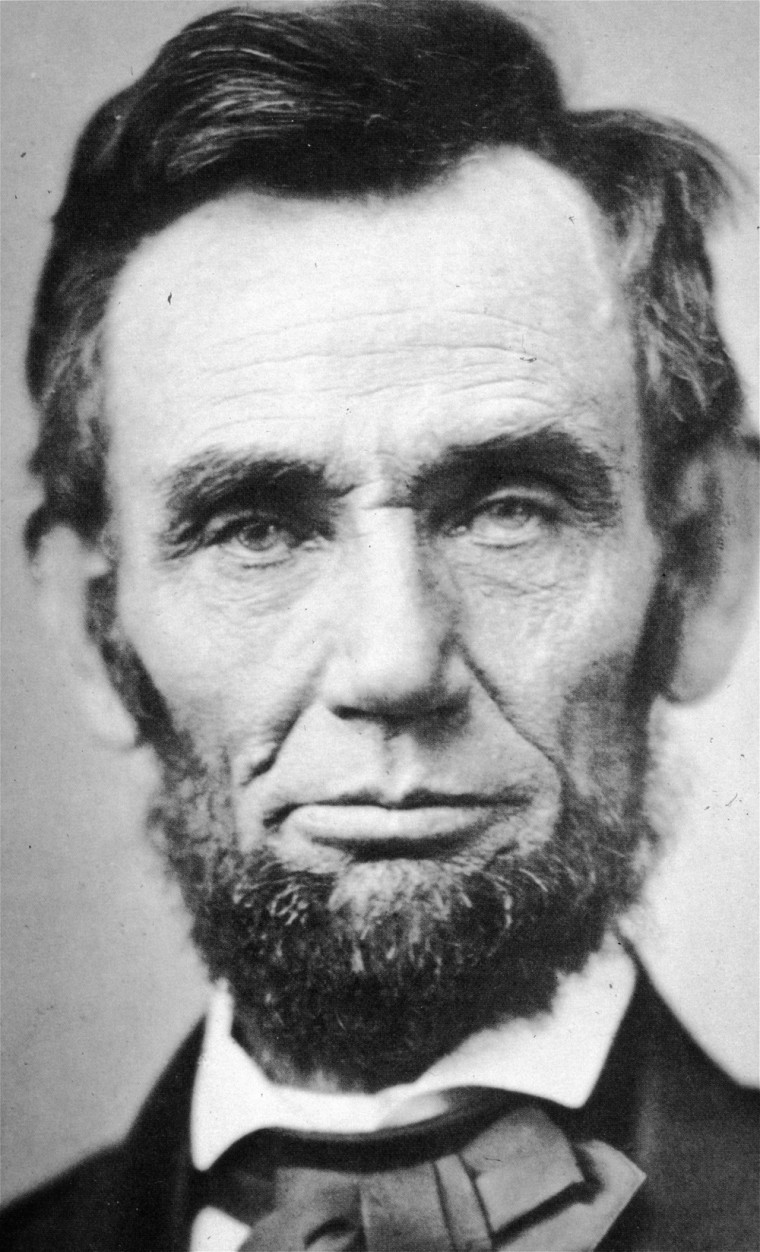

The Lincoln Memorial

Walk north from the Tidal Basin and you’ll come to the Lincoln Memorial. Look up at Daniel Chester French’s haunting statue and you’ll be reminded why this martyred president has cast such a spell on his successors, including Obama.

It was here in the morning hours of May 9, 1970, that after a sleepless night, President Richard Nixon went for a spontaneous pre-dawn meeting with college student demonstrators who were camping out as part of a national protest against the Vietnam War. “I was trying to relate to them in a way (that) they could feel I understood their problems,” said Nixon.

Head north to Virginia Avenue — there you’ll find another landmark key to the Nixon presidency.

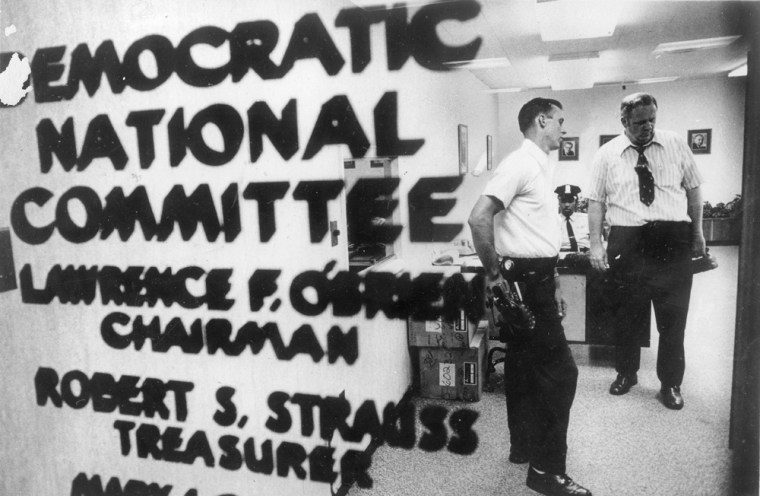

Nixon, Watergate and Wilson

Welcome to the Watergate complex, the building at the center of a political scandal for the ages. On June 17, 1972, a security guard named Frank Wills discovered that someone had broken into the offices of the Democratic National Committee on the sixth floor. That burglary and Nixon’s attempt to impede the subsequent investigation ultimately to his resignation in 1974.

Across the street is a former Howard Johnson Motor Lodge where conspirators Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy kept watch from room 732. It’s now a George Washington University dormitory affectionately known as HOVA, or Hall on Virginia Avenue.

Another president whose time in the White House, like Nixon’s, ended tragically was Woodrow Wilson. He was felled by a stroke in 1919 as he led the fight to persuade the Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and create the League of Nations.

Head north to 2340 S St. N.W., and you’ll find the house where Wilson died on Feb. 3, 1924, just three years after leaving the White House. It’s now a museum dedicated to his life. You can take a tour.

He’s also the only president to be buried in the District of Columbia, at the National Cathedral, a mile and a half north of the Wilson house, near where Massachusetts Avenue meets Wisconsin Avenue.

Roosevelt’s rooms

A short stroll from the Woodrow Wilson house is 2131 R St. N.W., where Franklin Roosevelt lived when he served as assistant secretary of the Navy under Wilson. While living there, he began a romance with his wife’s former social secretary, Lucy Mercer. His wife, Eleanor, was summering in Maine when the affair began.

When the relationship was uncovered, Eleanor offered an ultimatum: end it or obtain a divorce. But he contained to see Mercer. And 30 years later, she was with the president when he died while sitting for a portrait in Warm Springs, Ga.

A few blocks from that house is the sumptuous Cosmos Club at 2121 Massachusetts Ave. N.W.

Originally known as the Townsend House, it was built for Richard and Mary Scott Townsend, whose families had made their fortunes from the Erie and Pennsylvania railroads.

The Townsends’ daughter married Sumner Welles, a blueblood whom Franklin Roosevelt had met at the elite Groton prep school. Welles later served as undersecretary of state for Roosevelt and was his trusted envoy.

According to Washington historian Mary Kay Ricks, who leads walking tours of Georgetown and Embassy Row, Roosevelt was supposed to stay at the mansion in the days leading up to in March 1933. “Some of his aides took him aside and said, ‘You better not stay there. This wouldn’t look good. There’s a Depression going on.’ He ended up at the Mayflower Hotel, which was perfectly acceptable because it wasn’t staying with one wealthy family living in a mansion,” Ricks said.

Lincoln’s life and death

For a shift of centuries from the 20th to the 19th, go to President Lincoln’s Cottage, where he fled the tropical miasma of lowland Washington and spent parts of the summer months during the Civil War.

Just three miles north of the White House, this two-story home was an early version of Camp David. Lincoln commuted to the cottage daily, often traveling the three miles alone on horseback.

The Gothic-revival styled home is located on the Armed Forces Retirement Home campus in northwest Washington, near the intersection of Rock Creek Church Road and Upshur Street.

From where Lincoln lived to where he died — head to 5216 10th St. N.W., and you’ll find the Petersen House.

Lincoln was brought across the street to this boarding house from Ford’s Theater, where John Wilkes Booth shot him during a performance of “Our American Cousin.” He died nine hours later on April 15, 1865. What is striking about the Petersen House is how tiny the bedroom is where Lincoln died, compared to bedroom where Lincoln slept in the White House. The boarder’s bedroom about the size of modern walk-in closet.

Up the block and around the corner from the Petersen House, you’ll find a Marriott hotel at the intersection of 9th and F Streets. This is the site of the old Herndon House. On the day Lincoln was shot, Booth and his fellow conspirators met here to plan their crimes: Booth would kill the president, George Azerodt would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Lewis Powell would kill Secretary of State William Seward. Azerodt’s nerve failed him; Seward survived his assassination attempt.

Capitol haunts

Head next to Capitol Hill, where you’ll find a wealth of presidential and near-presidential associations.

Fifteen senators have also served as president of the United States, including John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Warren Harding and Richard Nixon. (Obama will be the sixteenth.)

Nineteen presidents served in the House of Representatives at some point in their career, including Lincoln, but John Quincy Adams is the only person ever to be elected to the House after serving as president.

In the old House chamber, now called Statuary Hall, on the south side of the second floor of the Capitol building, you can find a brass marker inlaid in the floor at the spot where Adams suffered a stroke in 1848. He died nearby in the speaker’s office. Adams had spent much of his service in the House from 1831 to 1848 fighting against slavery.

A few feet away from the Adams plaque in Statuary Hall is a statue of another president, the president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, who had served two stints as senator from Mississippi and in between served as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce.

Also in Statuary Hall are statues of four would-be presidents: William Jennings Bryan, who ran three times and failed; Robert La Follette, who ran in 1924 as the Progressive candidate and won 17 percent of the popular vote but carried only his home state of Wisconsin; Henry Clay, who lost in 1824, 1832 and 1844; and Lewis Cass, who lost in 1848.

On the Senate side of the Capitol and down one floor is the Old Supreme Court Chamber, where the justices met from 1810 to 1860, and where Adams argued the famous Amistad slave ship case in 1841. As you head into the old Supreme Court chamber, you will pass a bust of Chief Justice Roger Taney, appointed to the high court in 1836 by Andrew Jackson.

In his campaign for president, Lincoln was scathing in his denunciation of Taney and his 1857 Dred Scott decision, which strengthened constitutional protections for slavery.

On March 4, 1861, when the time came to swear in the new president, witnesses described an “agitated” Taney, trembling “with age or with anxiety,” and looking to one witness like “a galvanized corpse” as he administered the oath of office to Lincoln. (Historian Harold Holzer tells the story in his new book on Lincoln as president-elect.)

Supreme Court connections

Across the street from the Capitol is the Supreme Court. It’s the best possible place to reflect on the immense power presidents have to pick the justices who can overturn any law passed by Congress.

This is where the 2000 Florida recount was ended, essentially awarding the presidency to George W. Bush

This is also the place where Charles Evans Hughes, the only Supreme Court justice ever to run for president, worked. After resigning as a justice of the Supreme Court in 1916, Hughes ran as the Republican candidate in 1916 but lost to Wilson. The difference was just a few thousand votes, or a fraction of 1 percent of the vote, in California.

President Herbert Hoover appointed Hughes as chief justice in 1930. There’s no portrait of Hughes in the area of the court open to the public, but on the ground floor of the court is an exhibit on the laying of cornerstone of the building on Oct. 13, 1932.

There you can find a photo of Hughes giving a speech at that ceremony as a grim-looking Hoover in a top hat sits listening. Hoover would be defeated by Franklin Roosevelt the following month.

Across from the court building, at 100 Maryland Ave. N.E., is the United Methodist Building, a reminder of the human costs that presidents’ ambitions sometimes have.

On the morning of July 14, 1937, a maid entered an apartment in the Methodist Building and found the body of Senate Majority Leader Joe Robinson of Arkansas.

Robinson’s death of a heart attack marked the climax to the bitter battle Franklin Roosevelt had waged with Congress to expand the Supreme Court by up to six members.

Roosevelt’s “court-packing” plan grew out of his frustration with conservative justices striking down his New Deal legislation.

Robinson’s death helped turn congressional opinion against the court-packing scheme. Because of deaths and retirements, Roosevelt would in the end get to appoint eight members to the court, including Williams O. Douglas, in 1939.

In 1944, when FDR was looking for a new vice president to replace the eccentric Henry Wallace, he listed both Douglas and Sen. Harry Truman of Missouri as his choices in a letter sent to Democratic Party chairman Robert Hannegan.

“I should be very happy to run with either of them,” FDR wrote.

But party bosses much preferred Truman. Thus Truman, not Douglas, became president when FDR died. So, as with Hughes, the Supreme Court building is a reminder of another almost-president, Douglas.

Octagon House

End your tour with a president who was forced to defend America against an invading army.

Two blocks west of the White House at 1799 New York Ave. N.W. sits the Octagon House, designed by Dr. William Thornton, the first architect of the Capitol. It served as the temporary home for President James Madison after British soldiers torched the White House during the War of 1812.

The second floor study above the entrance is where Madison signed the Treaty of Ghent, ending the conflict with Great Britain.

Interestingly enough, one of the war’s greatest fights, the Battle of New Orleans, was to take place a few days later. News of the treaty hadn’t yet reached New Orleans.

In politics, timing is everything.