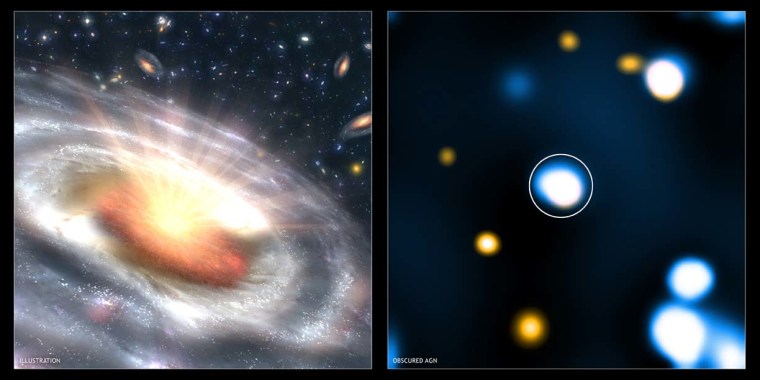

Supermassive black holes are thought to lurk at the heart of essentially all galaxies bigger than our own. Their powerful gravity should be luring in galactic matter, feeding the black holes' voracious appetites.

However, while plenty of gas is available for these black holes to feast upon, few of them have been observed to actively accrete gas from their home galaxy, presenting astronomers with a puzzle as to why these black holes aren't eating. Something must be preventing the black holes from accreting gas, though no one has known exactly what that was.

"This has been a longstanding problem," said Q. Daniel Wang of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Now, Wang and his colleagues have some possible suspects behind the starving black holes: exploding stars, or supernovas.

Wang and his team investigated the starvation of the supermassive black holes at the center of two galaxies, M31 (aka the Andromeda Galaxy, our nearest galactic neighbor) and NGC 5866. They presented their findings here this week at the 213th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

With both of these galaxies, and others, the precise clue that the galaxies aren't feeding is the lack of large amounts of radiation coming from the nucleus of the galaxy, which astronomers would expect to detect from an actively eating black hole. What makes the lack of radiation most perplexing is that plenty of gas should be expelled by older stars and their remnants, such as planetary nebulas, and accumulating in the galactic bulges of the galaxies (the tightly-packed group of stars found in the center of galaxies, where the black hole resides).

What was happening to that gas has been a mystery. Astronomers had surmised that the gas "has to be removed continuously from the bulge," Wang said, otherwise the black holes would be feasting on it.

Some astronomers thought gravitational influences from nearby galaxies could be sucking away the gas. But Wang's study suggests it's actually an internal problem generated by powerful supernova explosions.

These explosions occur when a massive star's core stops generating energy and collapses in on itself, releasing energy that heats and expels the star's outer layers — the star goes supernova.

Supernovas come in slightly varying types.

Type 1a supernovas are constantly exploding throughout a given galaxy. These exploding stars send out a shockwave — what Wang calls an "interstellar tsunami" — that propagates throughout the gas in the galaxy. Wang and his team simulated the effect of these shockwaves on the gas accumulation around the galaxy's center.

The interstellar tsunami works in a similar manner to tsunamis on Earth: The shockwave generated by an earthquake below the ocean has little effect where the ocean is deep and can absorb the energy, but when that wave reaches shallow water, it forms the characteristic enormous wave that slams onto the coast.

Likewise, the hot gas in the galaxy can absorb the supernova's shock, but when the wave reaches the cool gas expelled by dying stars, it steepens and pounds the central disk of the galaxy, evaporating the gas.

Because these supernova explosions are happening all the time, they continue to pound away at the disk; the gravity of a less massive galaxy can't counteract the evaporating energy of the supernovae, so the gas can't accumulate, and the black hole starves.

The interruption of the gas accumulation also affects the evolution of the galaxy, Wang noted.

More massive galaxies, on the other hand, have a bigger gravitational pull that keeps the gas from leaving.

"It's a much more difficult escape," Wang told SPACE.com. "Eventually gravity wins."