The work has always been stupefying and hard. Hour after hour standing on the line, soldering or welding or drilling in screws until tears join streaming sweat and hands cramp in pain.

Even in today's nightmare economy, most people wouldn't want this daily grind that steals the soul in 12-hour shifts paying as little as $280 a week, before taxes.

But such labor prospers here in mostly rural Jones County, home to Laurel, where the area's biggest employer, Howard Industries, maintains a sprawling factory that builds electrical transformers and other big equipment behind a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire.

Assembly lines like these offer tenuous lifelines to those desperate enough to toil on them. And sometimes, competition for these jobs pits have-nots against have-nots.

For a long time, Howard workers were poor blacks and whites in this town of 18,000, where an estimated 30 percent of the population lives in poverty.

But in the past few years, immigrants poured across the Mexican border, eagerly applying for work on the Howard line and not complaining about long hours or menial labor. Family members followed, until the racial palette of Laurel shifted from black and some white to abundant shades of brown.

But a festering resentment began to take root in the hearts of some black and white residents, producing an odd alliance in a place that has seen racial hatred. Now, even the Ku Klux Klan has turned its hatred against Hispanics.

Many blacks and whites claimed Hispanics were taking over their city and taking away jobs by not complaining about safety issues in a factory that faced $193,000 in fines last year from federal inspectors citing dangerous working conditions.

A disgruntled union member allegedly tipped the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, whose agents swept in last summer and staged the largest single workplace raid.

As nearly 600 Hispanics were herded past black and white Howard employees, jeers and applause and wide grins erupted.

"Bye-bye," some trilled in falsetto, fingers wagging. "Go back where you came from."

And the assembly line rattles on. But now mostly blacks work it, with a smattering of whites, for the same wages paid to Hispanics. The plant, which has been working without a union contract since August, is mired in bitter negotiations over higher pay and safety issues.

Plant busts

Workplace raids reached an all-time high in 2008 with 6,287 arrests — a tenfold rise since 2003. After the 9-11 attacks, in the name of national security, the Bush administration announced it wanted to detain, and then deport, every illegal immigrant in America. Such a drastic change in immigration policy was necessary to safeguard the country against terrorists, said the newly formed Department of Homeland Security.

Sweeping immigration reform bills — which included eased access to citizenship, along with tightening border controls — failed in Congress. Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff escalated the raids.

But swooping down on low-paying jobs has yet to produce terrorism suspects. Asked if any of the raids had produced terror-related arrests, ICE spokeswoman Barbara Gonzalez replied, "Not to my knowledge."

Across the country, such raids have netted sweatshop workers in Massachusetts, kosher slaughterhouse employees in Iowa and federal courthouse janitors in Rhode Island.

In some places, the aftermath has been devastating. The northeast Iowa city of Postville reeled after 389 workers at the Agriprocessors plant were arrested. The kosher slaughterhouse is now closed and bankrupt. Its owners face federal charges for allegedly helping employees obtain fake citizenship documents.

But the biggest roundup — 592 people arrested, mostly for the crime of illegally entering this country — was here in Laurel.

Since then, 414 Hispanics have been deported; 23 have left voluntarily and 27 were released on bond pending immigration hearings. One remains incarcerated at a federal detention center in Jena, La. Nine were charged with identity theft for using false identification.

More than 100, mostly women with children, were released pending the outcome of their cases. They wade through a long, confusing current of immigration hearings that will determine their futures. Many fear venturing out, lest they receive withering glances in the Wal-Mart aimed at the electronic monitoring devices on their ankles.

Immigrant groups, religious leaders, and various Democrats have expressed hope that the raids will be curtailed under President Barack Obama. The immigrants in Laurel know this, and they hope Obama's promise of change applies to them.

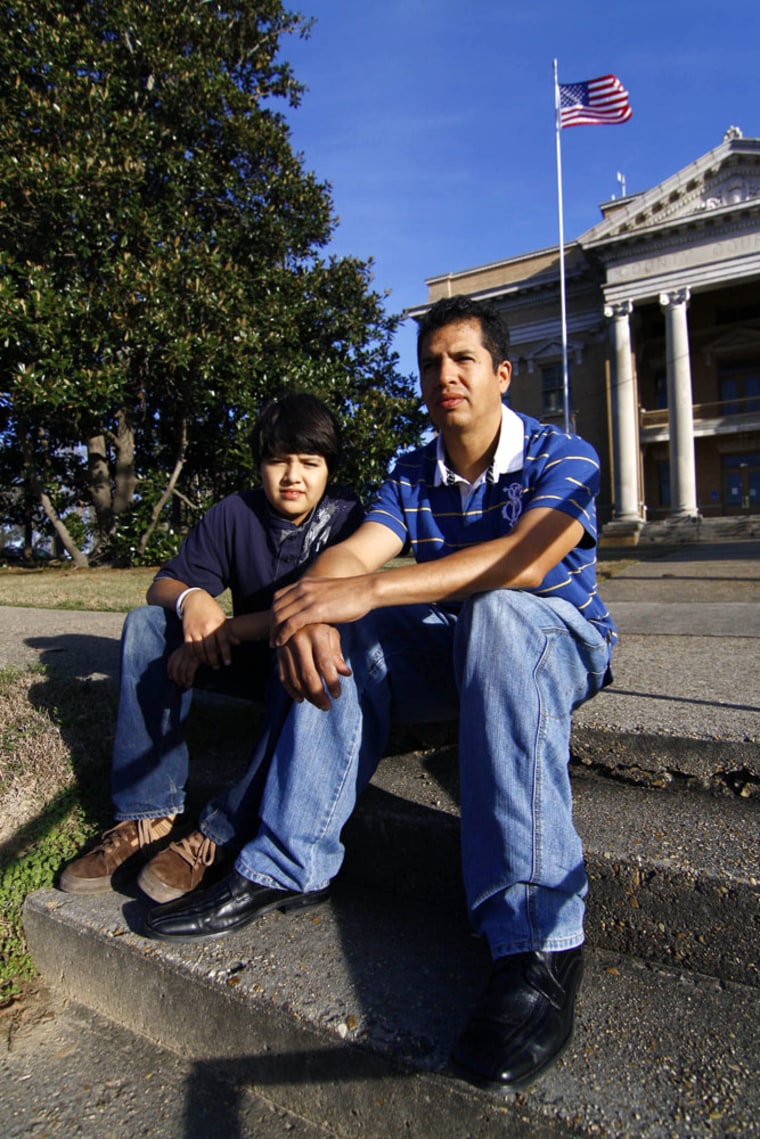

"We do the jobs no one else wants to do," says Ismael Cabrera, a 37-year-old father of two. "We just want to work."

He paid a smuggler $2,000 to walk him across the desert into Arizona. He paid $1,000 more to get a ride to Laurel, where he first worked in a poultry plant, wielding a small knife to slash the wings off dead chickens as they blurred past. His all-time high: 39 birds per minute.

"It's not that we took the jobs from other people," he says in Spanish. "It's that they don't want to work them."

He joined Howard as a welder three years ago, when hiring soared after Hurricane Katrina pulverized the Southeast and rebuilding began. When ICE agents descended in August, with handguns strapped to their thighs, people screamed. Some ran for the exits. Cabrera knew he was caught. "I just waited for what would happen," he says.

What followed was a month of incarceration at the Louisiana detention center while bail money was scraped together. "It was terrible," he said. "The guards called us bad words," which Cabrera refused to repeat in front of his son.

He waits on deportation hearings that he doesn't understand. He weeps at the prospect of going back to his hometown near Mexico City, where he made little money. His son, Cesar, has few memories of that place. He left when he was 6.

Now a sweet-faced boy of 13, Cesar respectfully interprets for his father in perfect English delivered with a Mississippi drawl.

Cesar is asked how he feels about going back to Mexico.

The boy looks to his father for guidance, who sits across from him on a hard wooden pew at the small Pentecostal church they attend. Cesar's gaze drops to his feet. His eyes brim with tears. He wipes his nose with the back of his wrist. "Bad," he manages to get out. "It would feel bad."

He shuffles out of the sanctuary, staring at the carpet. Cabrera watches his son go, then wipes his own face with the sleeve of his shirt.

"Sometimes I ask myself if it was worth it to come here," he says in a voice just above a whisper. "To gain insults and to be humiliated."

He has a 6-year-old daughter born in this country. "I'm not here because I want a lot of money. I want to work. I want a good education for my kids."

Local 1317 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers had been making a special effort to sign up Hispanics, estimated by the union to be about 40 percent to 60 percent of the Howard work force. It had signed up about 150 before the raid, said the local's president, Clarence Larkin, who is African-American.

Those new members are now gone, and with them, Larkin said, went a budding sense of solidarity.

The turnover rate for non-Hispanics is 40 percent, he said. There was very little turnover among Hispanic workers, which deepened the divide between the groups.

'Divide and conquer'

Blacks and whites thought working conditions might improve if immigrants weren't so eager to take whatever was offered. Hispanics, many of whom were sending money home to relatives, thought the others just didn't want to work hard and didn't appreciate the benefits of living in a wealthy country.

"As long as you can keep people at odds with each other, that drives out the union," Larkin said. "It's divide and conquer. To be successful, you have to be united. And this made the union weaker."

ICE spokeswoman Gonzalez said the raid came after a union member called two years ago to complain about undocumented workers at the plant.

Larkin said he doesn't know if that's true. "There were some complaints the Hispanics were shown favoritism because they loved to work long hours," Larkin said. "They complained less. They were less problematic. The company could exploit the Hispanics. If you're not legitimate, you're not going to complain."

Burning torches

Blacks in Mississippi know plenty about exploitation. Laurel itself had long been Klan territory, where hooded, robed men carrying burning torches marched proudly down the main thoroughfare before the civil rights movement.

White Knights Imperial Wizard Sam H. Bowers, suspected in hundreds of attacks including the infamous "Mississippi Burning" murders of three voter registration workers, lived in Laurel.

In 1998, Bowers — whom Time magazine called "the most dangerous man ever to don a white hood" — was sentenced to life in prison for arranging another murder. This one occurred in 1966, when Bowers ordered a fire-bomb attack on Vernon Dahmer Sr., who dared to register fellow blacks to vote at his rural market outside Hattiesburg.

These days, hate has a new target.

"Time for Mexico and Mexicans to get the hell out!!!" blasts a recruiting message on a Klan Web site. In rallies staged in recent years in Laurel, Tupelo and other Mississippi cities, Klan members gathered to accuse Hispanic immigrants of being child molesters, job stealers and destroyers of the American way of life.

Last year, Mississippi passed the most restrictive law in the nation against undocumented workers.

On March 17, Republican Gov. Haley Barbour signed a bill making it a felony for an illegal immigrant to hold a job — carrying fines of up to $10,000 and prison sentences of up to five years. Employers are exempt as long as they've used the Department of Homeland Security's E-Verify system, a database of Social Security information dating to the 1930s, which the agency acknowledges contains typos and omissions. The law takes effect this summer.

Democrats here also have campaigned on anti-immigration platforms. In 2007, the Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance sent a protest letter to national Democratic Party chairman Howard Dean, saying Democratic candidates "are peddling racist lies against immigrants that violate the core of the party's progressive agenda. We do not need politicians whose only concern is getting elected."

'These are poor people'

Pastor Robert Velez, who leads a largely immigrant congregation of about 60 souls at his Pentecostal church, thinks he knows what was behind the immigration raid, and what continues to drive discord in this industrial city.

"It's politics," says Velez, an American citizen born in Puerto Rico. "It's to make them look like they're doing something about the border. And to satisfy politicians.

"But these are poor people. They just want to work. Now they can't."

More than 20 percent of Mississippi residents live in poverty — the highest rate in the country, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Added to those rolls since the raid: Cabrera, his son Cesar and many others.

One is a woman named Mary, who didn't want her last name used because she said she has cut a deal with federal prosecutors investigating whether Howard Industries knowingly hired illegal immigrants using false identification. "The investigation is ongoing," said ICE's Gonzalez.

A spokeswoman for the company, which has not been formally accused of wrongdoing, declined comment. Previously, Howard officials have said they used every means available to check the immigration status of job applicants, and never knowingly hired an undocumented worker.

Mary was a solderer on the line for $11 an hour. The burning light and noxious fumes seared her eyes until she wept. She can no longer read up close and she can't afford glasses. She hopes her help to federal investigators will gain her a work visa to replace the fake ID she bought here.

Cabrera scrapes by doing odd jobs like cutting grass. His wife sells bread. He, too, purchased forged ID cards.

Sometimes the Social Security numbers are real and belong to real people, including people in trouble with the law. One worker in Laurel, whose purchased Social Security number belonged to a deadbeat dad, paid the man's child support to keep from being discovered.

But Laurel's factory raid targeted only illegal immigrants, not the people who sell them bogus documents costing anywhere from $60 to $200 a piece.

Cabrera doesn't know what will happen to him, or what he will do if deportation is ruled his fate.

Angelica Olmedo, a 32-year-old single mother, has already decided what to do. She will volunteer for deportation to Vera Cruz, where her parents grow sugar cane. She hopes that decision will ease the way for her to someday legally return to this country.

Immigration officials have held out that hope to those willing to go quietly, she said.

Her 13-year-old son, who was 5 when she paid for him to be smuggled to Mississippi, will return with her. After she was swept up in the Howard raid, where she repaired forklifts for $10.25 an hour, she said immigration officials released her on "humanitarian" grounds because she was a single mom.

She was outfitted with an electronic ankle bracelet and told not to leave the state. "I feel like a dog," she said, sitting in the doublewide trailer she shares with her sister, her brother-in-law, their two daughters and her son. "They told me I have charge it every two hours, and I said, 'What am I? A cell phone?'"

It took about two months for Olmedo to realize that apparently no one was monitoring the devices. In time, the clumsy plastic device slipped off her foot. No one from ICE has said a word to her since.

"It's to shame me," she said. "That's all it was, to shame me. To make me look like a criminal. But I am not a criminal, I was only working."

Another woman wore her anklet to Jena to visit her jailed husband. "She crossed a state line and walked right through the metal detector," said pastor Velez. "It's a joke. It's just to make them scared."

Another worker, a gay man who was released on humanitarian grounds because he feared his sexuality would get him assaulted in jail, keeps his bracelet on a living room table, next to a bowl housing his pet crawfish.

Olmedo regrets she can no longer work and contribute to her sister's household. She baby-sits her two small nieces during the day as partial payment for rent and food. "I don't even like to go out," she says. "I feel like everyone is watching me and knows I was in the raid.

"People stared and pointed at us when we were wearing the ankle bracelets," she said. "They talked to each other like we wouldn't understand." But Olmedo knows enough English to piece their words together.

"They were saying it was good what happened. They said I was illegal and that we should all be sent back to our own country."

Yet Olmedo has met kindness from some former co-workers. "I had friends. African-American and white. They come and ask if I need money for food. I don't take it. They brought shoes."

At Howard Industries, where the day crew is just getting off, a freezing rain pelts workers walking to their cars, heads bowed to shield their faces.

They are mostly black and mostly male. Some carry the stooped shoulders of the bone-weary. Others bound toward the employee parking lot with the glee of the newly freed.

Larry Jones, 24, sits in his car with the heater blasting, sucking the life out of a Swisher Sweets cigarillo. He has been on the job as a coil winder for two months.

The African-American man had tried to get hired before the raid, he said. "I filled out an application and took the test, but they never called me back."

Now he makes $8.20 an hour. And he is thankful for the raid.

"Now they got to hire us. The illegals will work for less than we will, and they'll work more. They were getting jobs everywhere."

He added: "I know they got to work, but it's rough over here, too."

He says he understands why people would try to escape the grinding poverty found in countries farther south, and why someone would sneak across the border. He feels bad for those swept up in the raid.

"In a way, I feel like it ain't right because these people are trying to better themselves. But on the other hand, we need jobs, too," he says softly. "A lot of folks 'round here were pretty happy about it, to tell you the truth. It was pretty much of a blessing for a lot of folks."