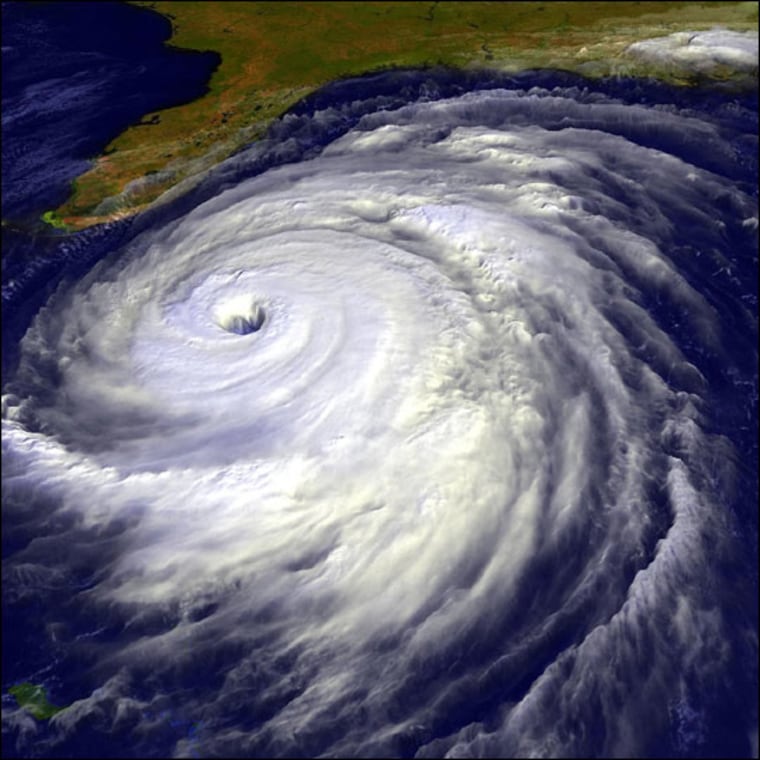

Just as a changing climate shapes the strength and frequency of hurricanes, the storms may have a huge effect on climate, leaving "footprints" in the atmosphere and ocean.

Hurricanes are infamous as harbingers of chaos — flooding cities, ripping houses to shreds, destroying beaches and even whole islands. And concerns are growing that human-induced climate change may lead to stronger storms whose intensity will wreak even more havoc on coastal communities around the world.

But the full interplay between hurricanes and climate remains an enigma.

Robert Hart of Florida State University analyzed two decades of climate data from the tropics, and found that each storm leaves a wake of anomalously cool water and warm air behind it that can persist anywhere from one to two months, depending on the storm's strength.

Scientists have known for years that hurricanes cause cool ocean waters to well up, but Hart was surprised at how long the atmosphere retained a "memory" of each storm.

That got him thinking: if one storm can have such a lasting impact, what does a whole season of storms do to Earth's climate? Would there be a difference in effect between an active hurricane season and a quiet one?

Hart performed a series of calculations and came up with a striking preliminary answer: hurricane seasons that spawned more storms (like 2005, for example) led to quieter winters in the northern hemisphere, and quiet hurricane seasons led to winters with lots of storm activity.

The reason, Hart speculates, is that hurricanes bring large amounts of heat out of the tropics and toward the poles. When a season has more storms, more heat is deposited closer to the poles and the tropics are cooled off more, so that when winter sets in there is less temperature difference between the poles and tropics.

"That's what winter weather is — movement of heat between the tropics and the poles," Hart said. "So it's possible that hurricanes do more than their fair share of the work during an active season, and there's less work to be done during the winter."

Gabriel Vecchi of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association's Geophyscial Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J., said Hart's work gets at some of the toughest questions in meteorology today: What are hurricanes? Do they serve a purpose?

"It may sound like a stupid question, but I wonder what tropical cyclones' role in the climate system is," he said.

There are two general theories — one which states that hurricanes are simply the result of more potent forces, like El Nino pushing vast amounts of heat and moisture around Earth's atmosphere. The other says hurricanes are vital heat engines that transfer energy from the tropics toward the poles. Through their fury, they are in fact bringing balance to the planet's climate.

"The list of results about how they affect climate is getting longer," Vecchi said. "This is all hinting that tropical cyclones do something profound."