A British court ruling to keep U.S. intelligence documents out of the public domain sparked debate Thursday over whether London had a responsibility in exposing the torture allegations of a U.K. resident held in Guantanamo Bay since 2004.

Two senior justices delivered a ruling Wednesday that said there was significant evidence to show Binyam Mohamed was either tortured or abused in U.S. custody, but there was not much they could do about making the documents public because of the British government's national security concerns.

Foreign Secretary David Miliband backed the ruling and said it was not for Britain to disclose U.S. intelligence data.

"I am not going to join a lobbying campaign against the American government for this decision," Miliband told Britain's House of Commons. "It's a decision they have to make, given their knowledge of the full facts in respect of the sources they depend on and the resources that they do not want to compromise."

President Barack Obama's administration has vowed to banish torture-induced interrogations and to close the U.S. prison camp in Guantanamo Bay where hundreds of men have been held without charge since it opened in January 2002 — four months after the Sept. 11 attacks.

Making detainee documents public could be a risky move for an administration trying to repair its international image, but Mohamed's imminent release from the prison camp could force Washington to answer some uncomfortable questions unanswered by the Bush administration.

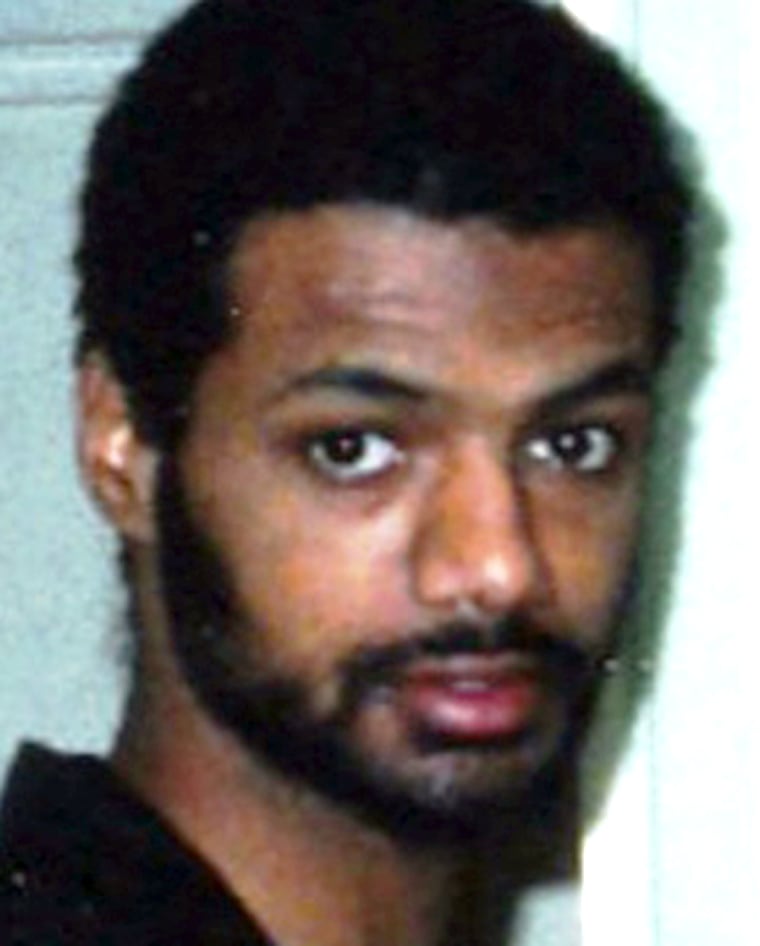

Mohamed, 31, was arrested in Pakistan in 2002, and claims he was tortured there for three months before Americans sent him to Morocco where interrogators tortured him. He claims his interrogators in Morocco asked him questions about things that only British intelligence agents could have known.

Evidence of 'serious wrongdoing'

Senior Justices John Thomas and Justice Lloyd Jones, who have seen all of the 42 documents relating to Mohamed, ruled the material detailing his treatment in American custody should be suppressed. But they protested they had no choice because the government had informed them of a "threat" by the U.S. to withdraw all intelligence cooperation with Britain if they were published by the court.

The ruling was in response to a legal challenge brought by The Associated Press, Guardian News and Media Ltd., British Broadcasting Corp., Times Newspapers Ltd., Independent News and Media Ltd., the Press Association and The New York Times.

The justices said they believed keeping some of the material secret amounted to concealing "the gist of the evidence of serious wrongdoing by the United States which had been facilitated in part by the United Kingdom government."

Britain denies it had knowledge of Mohamed's alleged torture or abuse. It also has said it only learned that Mohamed had been sent to Morocco to be interrogated a year after he had already been in Guantanamo.

Still, Britain's Attorney General's office is investigating claims that the government was complicit in the alleged torture.

Charges against Mohamed were recently dropped, but he remains in Guantanamo on a hunger strike.

"The issue at stake is not the content of the intelligence material, but the principle at the heart of all intelligence relationships — that a country retains control of its intelligence information and it cannot be disclosed by foreign authorities without its consent," Miliband said. "That is a principle we neglect at our peril."

Threat to national security?

Miliband filed a written submission to the court last year to say why the documents should not be made public. He said John B. Bellinger, legal adviser to the former U.S. secretary of state, sent a letter to his office in August to explain the possible consequences.

Disclosing the information "is likely to result in serious damage to U.S. national security and could harm existing intelligence information-sharing arrangements between our two governments," Bellinger wrote in the letter, which was made publicly available on Thursday.

Miliband also testified on the issue, but the session was closed to the media and public.

"It was and remains ... the judgment of the foreign secretary that the United States government might carry that threat out," the ruling said.

Miliband told lawmakers there was never any "threat," but Mohamed's lawyers accused him of misleading the judges and filed a motion Thursday asking the judges to reconsider their judgment and reopen the case.

"These admissions by the foreign secretary would seem to undermine the whole basis of the court's reluctant decision to refuse to publish those details," said Katherine O'Shea, a spokeswoman for the legal charity Reprieve, which represents Mohamed and several other Guantanamo detainees.

Rolling over

Ed Davey, foreign affairs spokesman for the opposition Liberal Democrats, said a close ally like the United States would never cut Britain off from vital intelligence information.

He said the government had "rolled over in the face of a scarcely credible threat from a friend."

Opposition Conservative Party lawmaker Andrew Tyrie said Britain's Intelligence and Security Committee should review the 42 documents urgently.

"It is clear from the High Court's ruling in this case that the Intelligence and Security Committee was misled about the involvement of the UK Security Service in the mistreatment of Binyam Mohamed," Tyrie said.

Miliband said he recently spoke to U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton about Mohamed's return.

He said Mohamed's release would be "in full accordance not just with his rights but with British security considerations.

Mohamed is one of two British residents remaining in Guantanamo.