It was 2 a.m. when a rocket launcher sent a grenade slamming into the front gate of Hafizullah Shahbaz Khiel's walled compound. Screeching children and women ran into a small underground room. American and Afghan soldiers shouted: "Get over here, get over here. On the floor, heads down."

Hafizullah, a former Guantanamo prisoner, knew not to resist. And so, his family says, he was wrongly taken into custody by the United States — for the second time.

Hafizullah's story shows just how difficult it is for the U.S. to determine who is guilty and who is not in Afghanistan, where corruption rules and grudges are held for years, if not decades. It is a conundrum that the U.S. faces as it prepares to close Guantanamo and empty it of the 245 prisoners still there.

The first time Hafizullah was seized, in 2002, he spent five years at Guantanamo. In legal documents, the U.S. cites a source saying he helped al-Qaida and planned to kill a government official. But Hafizullah says he was turned in by a corrupt police chief as revenge, and the Afghan government cleared him of all charges in December 2007.

Less than a year later, in September, the U.S. raided his home. This time he was accused of treating sick Taliban as a pharmacist. Afghan officials have signed documents attesting to his innocence, but he is still in custody at Bagram Air Base, along with about 600 other prisoners.

Some Afghans claim the U.S. is far too quick to arrest people without understanding the complexities of the culture.

"We are fed up," says Ishaq Gailani, a member of President Hamid Karzai's government. "Bagram is full of these people who are wrongly accused. They arrest everyone — a 15-year-old boy and a 61-year-old man. They arrest them because they run away from their helicopters...I would run away too if I saw them. They don't know who is the terrorist and who is not."

The Associated Press has pieced together Hafizullah's story from legal documents and interviews with a former governor of Paktia province, family members, neighbors, a former mujahedeen leader and former cellmates at Guantanamo.

He had been held by Taliban as well

Hafizullah was a village elder and a father of seven, from a family that goes back to generals and brigadiers in the army of Afghanistan's King Amanullah Khan at the turn of the 20th century.

In 1998 he languished in a Taliban jail for several months, beaten and accused of opposing the Taliban. Fearful of the religious militia, he relocated his pharmacy to his home. People in his rural district of Zormat called him doctor and came to him for treatment.

In the heady days that followed the Taliban's collapse in December 2001, Hafizullah was appointed a sub-governor. He was named to a provincewide shura, or council, designed to unite government supporters and neutralize the Taliban and hostile warlords.

"I know Hafizullah very well. I appointed him to the shura," says Raz Mohammed Dilili, governor of eastern Paktia province at the time. "He was respected by the people of his district of Zormat."

The council decided that anyone found opposing the government would have their homes burned down and would be fined about $50,000. It also invited those who had been with the Taliban to come to the government or pay a fine of about $20,000.

Hafizullah was tasked with keeping law and order in Zormat. That's where he ran afoul of Police Chief Abdullah Mujahed.

Dilili, the governor, describes Abdullah as a scoundrel who would have his men fire rockets at U.S. forces, then blame his enemies and turn them over to the Americans. Abdullah and Hafizullah already had a history of enmity after serving in different mujahedeen or warrior groups in the 1980s.

In 2002, Hafizullah traced a robbery of nearly $3,000 to the police chief, Abdullah, and his men, according to Dilili as well as family members. The cars involved in the robbery were parked in the police chief's compound, he found. He confronted Abdullah.

The next day, U.S. forces picked him up as a suspected Taliban.

Legal documents obtained by The Associated Press from the Department of Defense cite several accusations against Hafizullah from an unnamed source — among others, that he led 12 Taliban and al-Qaida men and planned to attack the Afghan government, and that he doubled the salary of anyone who killed an American. The documents further state that Hafizullah's telephone number and name were associated with a Taliban cell, and that his brother had a car dealership in Zormat where he kept weapons.

However, the same documents note that Hafizullah said he was a victim of revenge and did not know why he had been arrested. Hafizullah also said he was not an al-Qaida member and in fact had helped the Americans in the past by giving them information about al-Qaida.

For the next five years, he was known by his identification number: 1001.

At Guantanamo, in Block 4, Hafizullah shared a cell with Hajji Ghalib for two years. The Associated Press found Ghalib, now released, to talk about Hafizullah. He lives in Afghanistan's eastern Nangarhar province.

"He never said anything bad about Karzai's government, but he was disappointed in them that they had supported corrupt people," says Ghalib.

Ghalib says his experience with Afghanistan's deeply corrupt police force is firsthand. After returning from Guantanamo, he went to the interior ministry with a letter of introduction from his former mujahedeen leader. Ghalib says they were ready to give him a job — for $600.

He didn't have the money, and is now unemployed.

Another former neighbor at Guantanamo with Hafizullah was Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef, the defiant Taliban ambassador after the attacks of Sept. 11.

"I didn't know him before Guantanamo. He was never a member of the Taliban," Zaeef says of Hafizullah from his Kabul home, at the end of a potholed street ankle-deep in mud and snow. "His beard was white, he was a very old man, he was very disappointed from the government and from the Americans too. He said, 'I don't know why I am here. I have no reason to be here. Someone was against me.'"

In a strange twist, Zaeef says he later saw Hafizullah's enemy — police chief Abdullah — in Guantanamo also. Abdullah was a member of the Northern Alliance, a ragtag army of mujahedeen turned warlords who were installed in power after the Taliban fell. The AP found him in Zormat, reluctant to talk.

Abdullah denied firing rockets on U.S. bases, but refused to discuss Hafizullah's case. An ethnic Tajik from the predominantly Pashtun province of Paktia, Abdullah told the AP he was a victim of tribal rivalries, turned over to the U.S. forces by rivals. He spent five years in Guantanamo.

Most detainees turned over to U.S.

It's typical for detainees to be turned in by others rather than caught by police, according to a 2006 report from New Jersey's Seton Hall University School of Law. The report found that only 5 percent of Guantanamo detainees were captured by U.S. forces, while 86 percent were arrested by either Pakistan or the Northern Alliance and handed to the U.S.

The U.S. military in Afghanistan refused to comment on either the first or the second detention.

"It has been a giant failure of intelligence. Most of the people the U.S. had were turned in for bounties and personal grudges," said Tina Foster, a U.S. lawyer representing several detainees both at Guantanamo and at Bagram. "The U.S. doesn't know who to trust and who to believe in Afghanistan, how to get good information."

Like hundreds of other prisoners, Hafizullah was caught in a four-year legal quagmire over whether they had the right to challenge the accusations that landed them in Guantanamo. He was released in 2008, just six months before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of prisoners' rights. So his lawyers never had the chance to take his case to court and clear his name.

Lawyer Peter Ryan with the Philadelphia law firm Dechert LLP suspects that is why Hafizullah is now in Bagram.

"Hafizullah's was a ridiculously weak case," Ryan says. "But the taint of that initial detention at Guantanamo has never been resolved. And when they arrested him this time, they must have found all his files and said, 'He must be a bad guy.'"

Upon Hafizullah's release in 2007, the Afghan government held him for three months and then cleared him of all charges. But in the September raid, Hafizullah and 13 others were arrested, including his brothers and three sons. The others were later released.

Hafizullah's U.S. lawyers are now challenging his detention at Bagram. Family members fear a decades-old feud involving a distant cousin, Fazle Rabi, may have been behind the nighttime raid on Hafizullah's home.

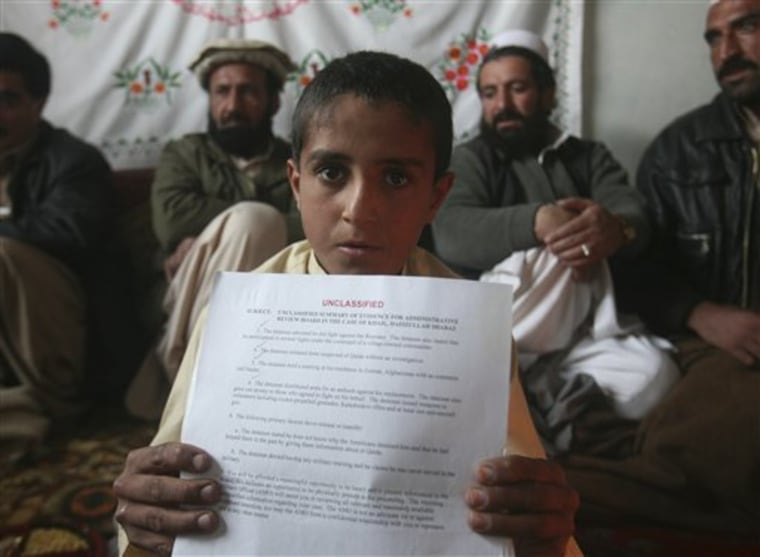

Zormat elders, leading clerics, the provincial governor, the National Reconciliation Bureau and two members of Parliament have signed documents attesting to Hafizullah's innocence. Armed with the documents, Hafizullah's brothers and young nephews are trying to get him released.

So far, they have had no luck, says Rafiullah Khiel, an English-speaking nephew who works in the finance ministry.

"No one is listening to our voice," he says.