Questions linger here, as ripe and nagging as the odor that once wafted over this former dairy capital: Who is trying to seize the home of Ray Vargas, child of the Great Depression, D-Day veteran and loving husband who just wanted to do right by his dying wife? And are they entitled to it?

In bankruptcy court documents, the party attempting to foreclose is identified as Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems Inc., or MERS, a small Vienna, Va.-based company employed by lenders to streamline the resale of mortgage loans and servicing rights. In that role, MERS claims an interest in tens of millions of U.S. home loans and the legal right to foreclose on those in default.

But MERS never gave Vargas a loan. It never collected money from him or recorded his payments. It had no ability to modify his loan.

What it did have was a copy of a document that named it a “beneficiary” of the mortgage on his home and a “nominee” for the lender and “lender’s successors and assigns.” But it has never identified the current holder of the loan.

'It makes me sick'

While such documentation has allowed many foreclosures to proceed around the nation, the judge in Vargas’ case threw MERS for a loop, ruling that the company had no right to attempt to seize his home on behalf of unnamed plaintiffs.

“No such unidentified parties are permitted in a motion before the court,” wrote Judge Samuel L. Bufford. Bufford’s October ruling kept the foreclosure on hold and opened the door for Vargas to sue MERS in an action aimed at clearing his home of the $826,549 in debt he says is the result of fraud, forgery and abuse of process.

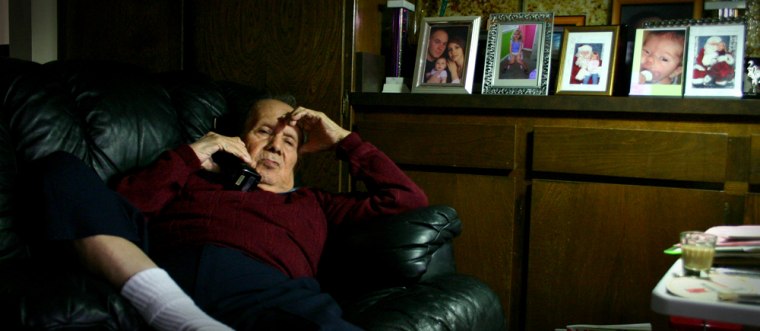

“It makes me sick,” said Vargas, 84, a deeply religious man who believes God is guiding him in a mission to expose wrongful foreclosure. “Greed has no bounds. That’s what the whole problem is: greed, greed, greed.”

Vargas' case has captured the attention of hundreds of attorneys and others immersed in the nation’s mortgage meltdown, which saw foreclosure filings on U.S. homes hit 3 million last year. In the first six weeks of this year, foreclosure began on another 296,000, according to the Center for Responsible Lending.

Legal icon is a new and somewhat surreal role for Vargas. The Chicago native who got his first job at 8 in the depths of the Great Depression has always been a realist.

From World War II vet to painting contractor

As a Navy corpsman during World War II, he went ashore with the third assault wave at Utah Beach on D-Day to pluck his fallen buddies from the sand and patch them up as best he could. Later, he owned a painting business and took on big jobs, like the restoration of the Queen Mary, the steamship turned hotel, in nearby Long Beach.

But Vargas, hero, citizen and family man, has been sucker-punched along with millions of other American homeowners, taxpayers and the nation’s entire economy by the mortgage-lending debacle.

A series of loans from some of America’s largest mortgage lenders cost him nearly $200,000 in less than two years and destroyed financial security it took a lifetime to build. Documents reviewed by msnbc.com show that loans sold to Vargas by mortgage brokers on behalf of the lenders were loaded with features that federal officials say are the hallmarks of predatory lending.

Lenders passed around the deed to Vargas’ house as if it were a whiskey bottle at a frat party. Ultimately, he wound up in foreclosure proceedings. And, finally, bankruptcy court.

Vargas’ story is the Cliff Notes version of what has happened to the larger American economy. It is a story of greed, lax lending standards, lack of government oversight and the fantasy that real estate prices will always rise.

Now, Vargas’ story, like the larger epic, has become a nightmare. The final chapters in both will be written by judges and lawmakers who, many would argue, should have taken up their pens much sooner.

Vargas’ story is complicated but it begins simply, with love — the love for a woman with whom he shared 57 years of marriage, three sons, three grandchildren and a cozy life in this suburban oasis, about 20 miles southeast of Los Angeles. Raymond Vargas loved Ophelia Martinez and she loved him.

They married and set up house in Southern California in 1948, two years after Ray mustered out of the service, having earned a passel of ribbons and medals for service in the American, European and Pacific theaters.

In 1971, after the family had outgrown its first home, Vargas made a down payment on a sprawling stucco two-story yet to be built in one of the many dairy pastures that gave way to the city of Cerritos, now an upscale enclave of 57,000 with tree-lined streets and posh facilities like a titanium-skinned library.

Vargas’ business flourished and he became a well-known civic leader, serving seven times as commander of the local VFW.

“I got more than I deserved,” he said, his eyes wandering to Ophelia’s paintings of landscapes and floral arrangements that adorn his living room.

Medical needs force new loans

The happiness ended in 2000, when Ophelia was stricken with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, brain tumors and a stroke that left her bedridden, unable to speak. She required expensive around-the-clock care, but Vargas was determined not to put her in a nursing home.

He spent the couple’s cash, closed out their retirement funds and tapped some credit cards. That left only the family home, which had been paid off for a dozen years.

After initially taking out a $50,000 loan with the family’s longtime bank, Vargas turned to a reverse mortgage in late 2003. Such loans, available to older homeowners, are attractive to retired, fixed-income borrowers because they require no monthly payments. Principal and interest are generally not repaid until the sale of the home, often after the borrower has died.

“I needed that money to pay my wife’s medical bills,” Vargas said. “I didn’t have to make any payments until I was deceased and then they would take their money out of my house and my sons would get the rest.”

Reverse mortgage maxed out

By the time Ophelia Vargas died on Jan. 4, 2005, the expenses for her care had maxed out the reverse mortgage. And Ray Vargas had become a target of services that cull through land records to provide sales leads to mortgage brokers. To anyone familiar with property values in Cerritos, the public information on Vargas’ loan might as well have been a banner saying, “Elderly homeowner with lots of equity to cash out.”

Vargas was inundated with offers to refinance, by phone, mail and in person. “There were so many mortgage brokers after me, it wasn’t even funny,” he said.

Vargas’ younger sister, Rebecca Deleon, said she often tried to shoo away loan officers during visits to Vargas’ home. “Every time I went over there, he had a new person that was trying to give him a loan,” Deleon told msnbc.com.

In need of additional funds for his own home care and a pair of car loans, Vargas finally agreed to a loan. He insists the salesman told him the deal would refinance his house with a new reverse mortgage requiring no monthly payments.

“They told me I didn’t have to send any money until I passed,” he says. “Then they started sending me all these bills.”

A refinancing merry-go-round

With that, he was trapped in a rapid cycle of refinancing that saw four lenders hold notes to his house in 2005 alone.

Vargas said he is still as sharp mentally as ever but admitted that he didn't read all the loan documents and was sometimes confused about the terms of the loans, partly because he had medical issues that for a time confined him to a wheelchair.

But he insisted that he never signed up for any loan he did not believe to be a reverse mortgage. And while he acknowledged that his signature appears on many documents, he claimed it was forged in connection with at least three loans. He also said he never went to any office to conduct loan business and never signed any papers before a public notary, although many of the documents bear notary seals.

“I never saw them,” Vargas said. “It was all telephonic. I never signed anything with them. I knew something was wrong.”

Although he made mortgage payments once he realized he owed them, he said he was constantly assured by those who sold him the loans that each new refinancing would eliminate them.

"He’s very straightforward and honest," said Vargas' attorney, Marcus Gomez. "He’s a little old World War II vet. He has no reason to lie. He thought he was getting money through another reverse mortgage and he needed it.”

An examination by msnbc.com of hundreds of pages of bank statements, escrow and loan documents provided by Vargas showed that over 21 months in 2005 and 2006, Vargas’ home was refinanced five times through a total of six loans.

Huge fees, penalties, interest

In that time, his debt grew from $213,555 to $745,000. To tap his $531,445 in equity, Vargas paid at least $123,237 in loan origination fees and prepayment penalties. He paid at least $60,000 in interest as he struggled to make minimum payments on the loans, giving the money right back to the lenders he had borrowed it from. Thousands more in unpaid interest was added to his debt.

Appraisals justified the loans. When they were made, the loans on Vargas’ house likely never totaled more than 90 percent of its value, which peaked close to $850,000 in 2006.

Foreclosure was the lenders' trump card and the equity cushion was their wager that they would not lose any money. Whether Vargas could make the payments was irrelevant.

Given the huge decline in California real estate prices, Vargas' house today is worth hundreds of thousands less than the $702,506 currently claimed in connection with the first loan and the $124,043 claimed on the second.

Signs of predatory lending

After the reverse mortgage, all of the loans to Vargas had one or more signs of predatory lending, practices that are not illegal unless they cross the line into fraud. However, federal officials have long warned of their harmful potential. "Predatory lending threatens to turn the American dream of homeownership into an American nightmare," then-assistant HUD Secretary William Apgar warned in congressional testimony in 2002.

Foremost, all of the loans were made with no regard for Vargas’ ability to pay them back. They were “option ARMS,” which gave him up to four choices each month of how much to pay. But in every case, the lowest option, generally not enough to cover that month’s interest, was more than his $1,600 a month income from Social Security and a union pension.

In other predatory features, at least three of the loans had hefty prepayment penalties. And three earned the agents who sold them a total of $35,475 in “yield spread premiums,” commissions paid by the lender to steer Vargas into loans that would yield more profit.

The first four loans were made by Downey Savings and Loan, World Savings Bank, Washington Mutual and Countrywide Bank, respectively.

Lenders all failed or nearly did

Because they made so many loans like those provided to Vargas — and others that were even more reckless — Downey and Washington Mutual failed and were seized by federal regulators last year. The collapse of WaMu, with $307 billion in assets, was by far the largest bank failure in U.S. history.

The parent company of World was taken over by Wachovia in 2006 in a move that is now widely seen as a big contributor to Wachovia’s failure and seizure last year. Countrywide was bought by Bank of America last year while on the brink of failure. It was subsequently sued by a dozen states over its predatory practices before BofA settled.

Representatives who work for the successor companies of World, Countrywide and WaMu all said they could not comment on specifics of Vargas’ case because of customer privacy concerns. Some of them said it is now widely accepted that mortgage brokers, like those who handled all of Vargas’ loans, often lied about borrowers’ income and other aspects of the deals.

A WaMu spokeswoman said the company, which was taken over by Chase, no longer accepts loans from mortgage brokers. Downey, which did not respond to msnbc.com’s inquiries, last year filed dozens of lawsuits that accuse mortgage brokers, borrowers and appraisers of lying on loan applications.

The high cost of Freedom

The final two loans on Vargas’ house were made by Freedom Home Mortgage Corp. of New Jersey, a first loan of $630,000 and a second of $115,000. They were made Oct. 3, 2006, and obligate him to pay over $3,700 a month — well more than double his income. Within months, he was unable to keep up with the payments. By early last year, foreclosure had begun.

Vargas, who spends a good part of each day watching TV news, said, he only recently came to comprehend that side of the vast financial scheme he was caught up in.

“God opened up my eyes” about what lies beneath the mortgage meltdown, he said. “He showed me what they were doing. They got all these loans and put them in the stock market in bundles. It’s incomprehensible.”

Indeed, Vargas' refinancing nightmare occurred during the peak years of mortgage securitization, the technique Wall Street used to turn home loans into bonds for sale to investors. Securitization in that time frame is now blamed for literally lavishing money on homeowners and buyers, often via predatory and subprime loans, and thus fueling housing inflation across the nation. And while lenders may not have considered Vargas a subprime borrower based on what mortgage brokers told them, his actual finances certainly made him one.

'Securitization meat grinder'

“A lot of the subprime lending, particularly the predatory loans, would not have occurred if the lenders had not been able to dump those loans into the securitization meat grinder,” said Bert Ely, a Cato Institute scholar and an expert on financial regulation.

Millions of those borrowers, like Vargas, are in the thick of foreclosure proceedings. Millions more have lost their homes.

Vargas got word in a letter last April 4 that MERS planned to auction the house three weeks later in a bid to regain what it said was owed in connection with the first mortgage. He retained attorney Gomez of nearby Norwalk, who rushed Vargas into bankruptcy court, a move that automatically stops, or stays, attempts to collect debts, including foreclosure.

Creditors in bankruptcy cases are allowed to seek removal of such stays, and that’s what MERS did, retaining attorney Mark T. Domeyer.

However, Gomez and Judge Bufford of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Central District of California wanted to know what right MERS had to demand the keys to Vargas’ house. After all, the loan in question had been made by Freedom, the New Jersey lender.

Domeyer’s court filings included copies of Freedom’s mortgage documents naming MERS as “beneficiary” of the deed of trust, or mortgage, on Ray’s house.

The use of MERS as a “nominee” of the lender and “beneficiary” of mortgages is key to the company’s business model, described on its Web site as “an innovative process that simplifies the way mortgage ownership and servicing rights are originated, sold and tracked. … MERS eliminates the need to prepare and record assignments when trading residential and commercial mortgage loans.”

In other words, when a loan in the MERS registry is sold by one party to another, instead of filing paper “assignments” at the local government office where the mortgage is recorded, the transaction is simply noted by MERS. Similarly, foreclosures and other events are supposed to be noted in MERS’ records on each loan.

57 million mortgages

With more than 3,000 member companies and 57 million registered mortgages covering about 50 percent of all new loans, the 45-employee MERS controls and disseminates information on loans made to a majority of American homeowners. MERS would not disclose how many foreclosure cases it is currently bringing.

In a press release in May 2007 when it announced the registration of its 50 millionth mortgage, MERS said it had saved the mortgage industry $1 billion since it was founded in 1996.

But consumer advocates see the company in a darker light, arguing that another purpose of MERS is to obscure ownership of loans, allowing investors to buy, sell and foreclose on them in unethical and illegal ways. Also unhappy are local government officials who miss out on assignments and recording fees.

Attorneys who defend homeowners in foreclosure say the procedure is reserved for the actual owner of the loan, also called a note. “The party who can bring a foreclosure proceeding has got to be the party that proves it actually owns the note and that note has been properly negotiated all the way up the line,” said O. Max Gardner III, a bankruptcy attorney from North Carolina and a dean of the U.S. debtor bar.

Mixed results in court

MERS officials and their attorney, Domeyer, declined requests from msnbc.com for interviews. MERS also declined to answer numerous questions submitted via e-mail, including who is actually the current owner of the loan, although it did provide a prepared statement that said in part, “Numerous state and federal courts have affirmed the right of MERS to be the mortgagee in the public land records and its ability to move for relief from stay and foreclose.” But Arnold’s statement also acknowledged that MERS’ guidelines for foreclosure appeared not to have been followed in Vargas’ case.

The argument that MERS lacks legal standing to foreclose has met with mixed results in court. MERS has won several such cases in Florida; debtors have won in Ohio, Connecticut and elsewhere.

Gardner said a nationwide ruling that MERS had no standing to foreclose would raise thorny issues. “What if a court really ruled that all these foreclosures that MERS has done are invalid?” he asked. “Can you imagine what would happen to the real estate and title business?”

Bankruptcy court rulings on MERS are being keenly watched because that is where many foreclosure cases are playing out and where many more could wind up.

So Judge Bufford’s ruling in Vargas’ case was greeted with enthusiasm by Gardner and his allies. In a withering opinion, the judge said MERS “presented no admissible evidence” in its case. And he found that sanctions should be imposed against Domeyer, the attorney representing MERS, for bringing such a sloppy motion to court.

The bottom line, Bufford said, was that the true owners of the loan — “highly unlikely” to be original lender Freedom — did not come forward in court and MERS failed to prove any right to act on their behalf. He would not comment to msnbc.com beyond his published ruling.

Bufford’s ruling opened the door for Gomez, Vargas' lawyer, to file a new claim. This complaint airs Vargas’ allegations of fraud and forgery surrounding the origination of the loan. In it, he seeks $1.75 million in damages as well as to remove lenders’ liens and his obligation to repay them via “quiet title.”

Freedom, the New Jersey company that originated the loans now in foreclosure, did not respond to interview requests.

The loans appear to have been sold to Vargas on behalf of Freedom by Monta Vista Mortgage, a now-defunct Santa Ana, Calif., firm that has disconnected its phones and moved out of its offices.

Signatures disputed

Vargas said the signatures on the loans are not his and that he never met with anyone from Monta Vista nor received settlement statements explaining the transactions.

Among the few papers Vargas has from Monta Vista are a letter and two check stubs showing he received about $48,000 for cashing out $95,000 in equity. It is unclear where the rest of the funds went.

Msnbc.com located the owner of Monta Vista, Martha Lozano, in nearby Tustin. She said she was running a new company, Debt Solutions, which helps trouble borrowers seek loan modifications from lenders. She said she could find no records in her computer system indicating that her old firm, which employed 50 to 60 people, had done business with Vargas. She said any paperwork on Vargas’ transactions had likely been stolen during a burglary at a storage unit.

Lozano said many homeowners in foreclosure “now want to blame us for everything that is happening to them.” But she defended the option ARMs sold to Vargas and others, saying, “You sell what the lender is advertising.”

Asked if she would have sold such a loan to her father, Lozano quickly replied, “No way!”

As to the claim of forgery, when msnbc.com tracked down the public notary who swore that Vargas had signed the documents, he said he had no recollection of the transaction. Thomas Montaghami of Anaheim, Calif., said he is no longer a notary. He said he had lost records that notaries are supposed to keep to explain how they verified the identities of people whose signatures they notarized.

Montaghami said he had informed authorities of the loss of his records as required, but officials at the Secretary of State’s Office in Sacramento said they had no record of that.

Shown a signature that MERS claimed was his on the loan it tried to foreclose, Vargas laughed. “That’s not mine.”

His attention was diverted by the ringing phone, a telemarketer trying to sell Vargas on refinancing his home. “It’s an everyday thing,” he said. “They’re the vultures coming to pick over the bones.”

The gallows humor fits Vargas’ lack of bitterness at his plight. A guy who began adulthood carting the dead and wounded away from Normandy may have a greater capacity for forgiveness than most.

Even if he loses the house, he reckons, it was out of love for his dear Ophelia. “We were married 57 years,” he said, softly, his eyes lighting upon an urn on his mantle. “Her ashes are right there. She will be buried with me when God calls me.”