It's a mystery that won't be solved as quickly as climate detectives had hoped. They'd expected instruments aboard a NASA satellite to detect where carbon dioxide emissions go, but the crash of that satellite on takeoff Tuesday could mean a long setback.

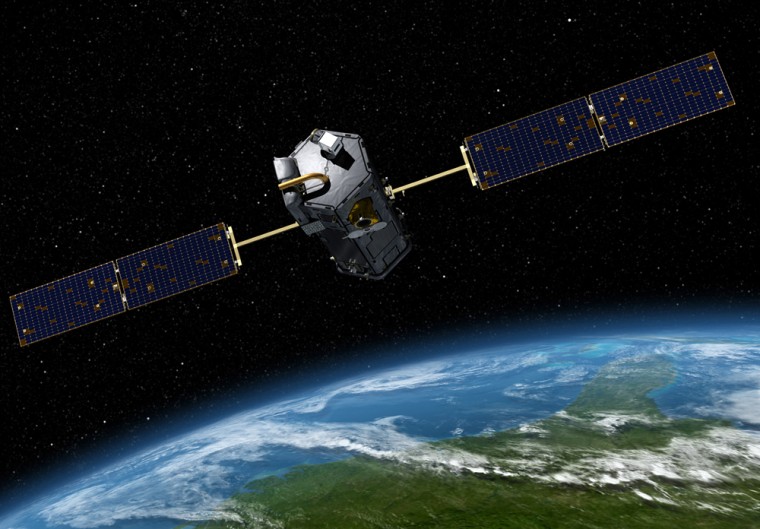

The $280 million Orbiting Carbon Observatory "was going to provide a revolutionary new view of the way the Earth 'breathes' CO2," said Scott Denning, an atmospheric sciences professor at Colorado State University who planned to analyze data from the mission. "It's a tremendous loss to our science community."

"The key issue for climate science is that about half of fossil fuel emissions are removed from the atmosphere by oceans and land ecosystems" via carbon "sinks," he added. That's important because emissions that don't go into the atmosphere don't add to the greenhouse effect tied to warming temperatures.

"In order to have any hope of predicting future CO2 levels we need to know how these carbon 'sinks' work, where they're located, how long the carbon will stay 'sunk' and whether there's anything we can do about it."

In effect, mankind has been getting a free 50 percent emissions reduction for decades but we don't really know why or how.

"OCO was going to provide data to let us make maps of the biological and oceanographic processes" that determine that, said Denning, "so it's relevant to policy as well because if the sinks saturate, the CO2 will rise much faster than it has been."

Policy and push-pins

The policy part is important given that the Obama administration, Congress and most of the world are moving towards regulating carbon and adopting policies to reduce emissions.

OCO would have provided policymakers with data on which policies work, said OCO program scientist Ken Jucks. "The question is, 'What impact do they really have?' Truly understanding how the system works will help us understand how best to implement those policies."

Phil DeCola, who was the OCO's program scientist for its first six years, echoed the notion that mankind has benefited from the 50-percent mystery. But, he added, "we don't know how much longer this can continue."

The hundreds of scientists working on OCO have been like police detectives, "trying to answer the big mystery of where is the missing carbon going," said DeCola, who is now an adviser at the White House Office of Science and Technology.

Losing OCO, DeCola said, limits "the speed at which we can address some of these important structural uncertainties."

Just how revolutionary was OCO? "We were hoping to start getting on the order of 100,000 measurements of atmospheric CO2 each day, from all over the world," said Denning. In contrast, the existing land-based CO2 network has fewer than 100 fixed towers.

Aircraft also take samples around the globe, Denning said, "but the difference is like looking at a map by reconstructing it from 100 push-pins instead of having access to the whole map."

Thinking positive

As disappointed as the team is, they're also determined to "get back on the horse," as DeCola put it.

Mike Freilich, earth science division director at NASA headquarters, told a press conference that engineers would look at existing spacecraft parts to see if it makes sense to build another carbon observatory.

Jucks and Denning noted that Japan last month launched a satellite that could also help.

The Japanese team is trying to "understand the processes that put CO2 into the atmosphere," Jucks said, whereas NASA was looking at where the CO2 goes.

Still, he noted, the teams "have been walking hand in hand" and the hope is that the Japanese satellite can still provide data on carbon sinks.

Denning, for his part, said he hopes "that NASA will fly a replacement mission, and there's also the possibility that an even better instrument (ASCENDS) will be flown in the coming decade, but of course developing and building these things is difficult, slow, and expensive."