Missing asteroids in our solar system may be the handiwork of rampaging giant planets as they migrated to their current positions, according to a new computer simulation.

Scientists have known that planets such as Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune migrated during the first several million years of early existence. The new simulation showed that the giant planets would have disturbed many asteroids as they fled the scene, leaving behind "footprints" that match the real-life patterns in the main asteroid belt.

"It really showed evidence that the footprints of planet migration are visible today in asteroid distribution," said David Minton, a planetary sciences researcher at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Patterns of planet migration

Previous evidence has suggested that the giant planets once formed a more compact huddle. But their gravitational interactions with the then-larger Kuiper Belt, an icy region beyond Neptune filled with comet-like bodies, ended up fueling a migration.

"Each time the planets tossed these Kuiper Belt objects around, they would move a little," Minton told SPACE.com.

Jupiter ended up moving slightly closer to the sun, while the other giant planets moved farther apart from both the sun and each other. Minton and Renu Malhotra, another planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, wanted to examine possible aftereffects of that unstable period.

Gaps as evidence

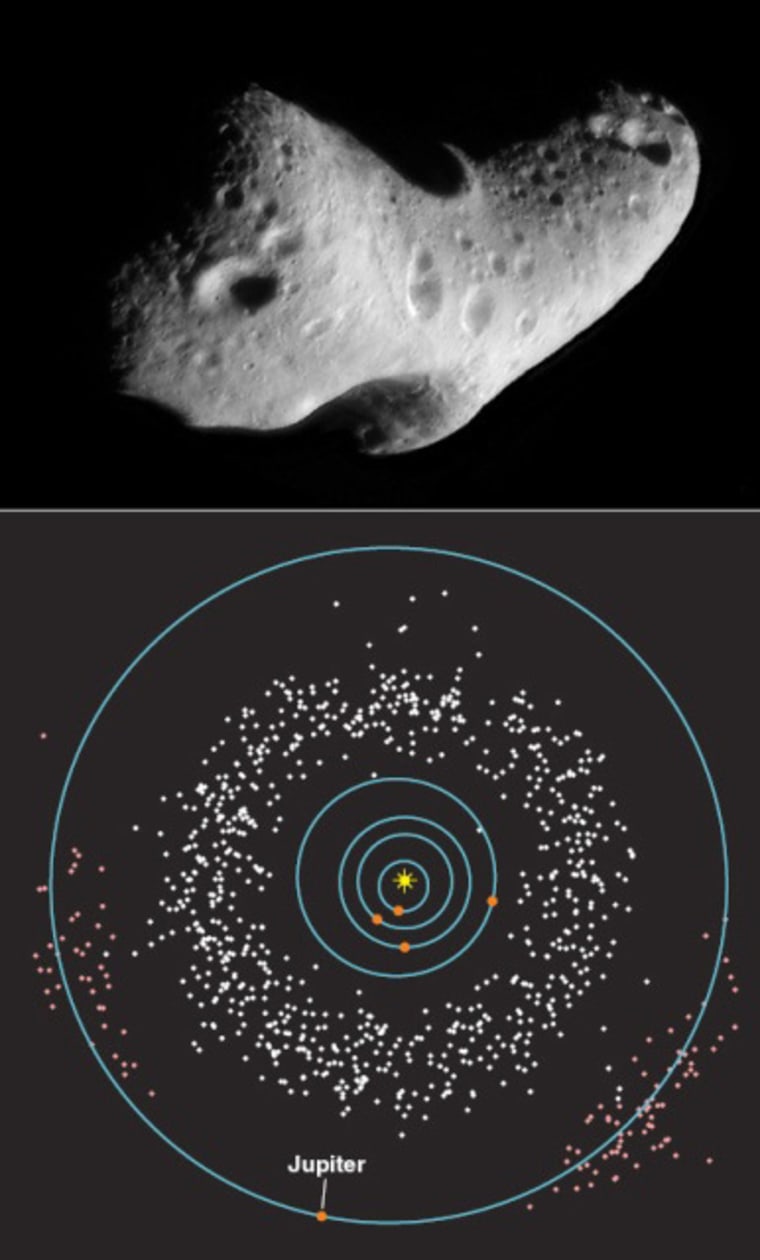

They first looked at the current configuration of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, which has remained largely stable for 4 billion years. Astronomers had discovered a series of gaps in the main belt known as Kirkwood gaps back in the 1860s. These unstable regions are relatively empty of asteroids because of Jupiter's and Saturn's current gravitational influence.

The researchers started their simulation with a uniform distribution of main belt asteroids larger than 30 miles (50 km) in diameter, but ended up with far more than what actually remains in real life. The simulated asteroid belt matched the real asteroid belt quite well on the sunward-facing sides of the Kirkwood gaps, but the real asteroid belt is largely devoid of asteroids on the Jupiter-facing sides.

That puzzle came together only when Minton and Malhotra ran other simulations which included the giant planet migration. The simulated asteroid patterns then matched up "surprisingly well" with the current main belt configuration, Minton said.

Collateral damage

Giant planets may have scarred our solar system in other ways. The inner system planets suffered a period of heavy bombardment around 3.9 billion years ago, which some scientists argue may have represented a spike in asteroid impacts rather than just the normal planetary formation chaos.

The new simulation may hint at the bombardment as being a collateral effect of the violent planet exodus, when main belt asteroids went zipping off like stray bullets.

"We can't say from this study when that migration happened, but it's a good plausible mechanism," Minton noted. "Once the asteroids get kicked out of the asteroid belt, they have to go somewhere. Earth, the moon and Mars are all great targets for these asteroids."

However, full closure on this case will have to wait for more evidence to turn up.