When the stars fall, sometimes it’s not what they did that kills or saves their sponsorship deals, but who they are.

Sometimes it’s not what they did, but what they’re selling.

And sometimes, yes, it’s all about what they did.

Those are the murky, muddy, ever-morphing ethics of the celebrity endorsement game, where bad acts committed by bad actors cause stern-faced corporations to (a) issue a huffy condemnation of the indiscretion but stand by their man or woman; (b) decline public comment; (c) decline public comment but privately praise the edgier image; or (d) bounce their famous spokesperson faster than a cereal can snap, crack and pop.

Some examples:

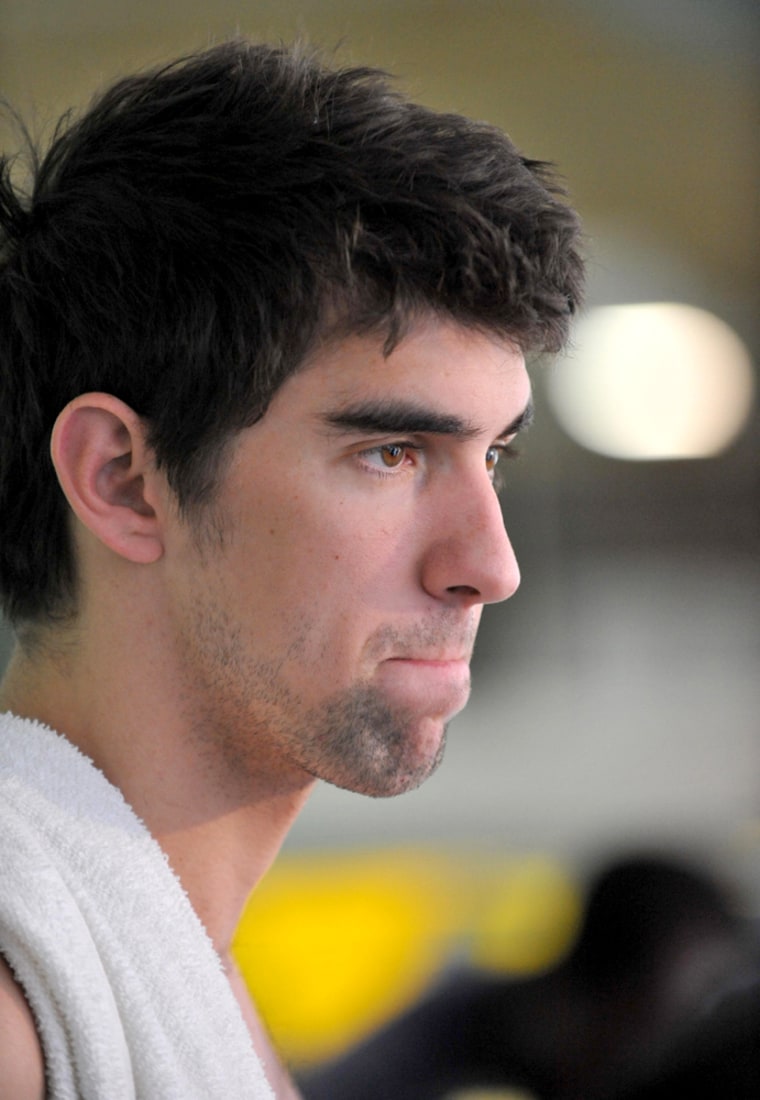

As Kellogg’s opted out of a contract extension with Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps several weeks ago, the company simultaneously ripped Phelps’ bong-hit photo as being inconsistent with its image. The next day, Subway formally announced it would plow ahead with a new ad campaign featuring the 14-time gold medalist.

Three days later, in the wake of New York Yankees star Alex Rodriguez’s admission that he once used steroids, Nike issued a statement saying that steroids are bad but adding nothing more about its endorsement deal with the baseball star. In 2006, Nike dropped Olympic gold medalist Justin Gatlin from its sponsorship stable three weeks after the sprinter flunked a doping test.

When it comes to the slip-ups that cause some sponsors to bolt and others to stick, the behavior bar — and where it is set — seems about as crooked as A-Rod’s many years of steroid denials.

The inconsistencies, sponsorship experts say, lie in a brand’s self-identity, a company’s read of current consumer attitudes, the spokesperson’s bank of goodwill and, in some cases, what other celebrity sins are making news that week. All those combine to twist the ethical lines.

A bad-boy or bad-girl image

“Kellogg is a family brand. How does Mom, who does the family shopping, feel about Phelps?” said David Reeder, vice president of GreenLight, a brand and entertainment consulting firm.

Subway would make a slightly different calculation, based on its target market of young adults, Reeder said. “Additionally, Subway may have so much invested in (Phelps) that they have little choice but to ride it out and hope the whole thing ends up in the rearview mirror.”

Nike, meanwhile, seems to be applying an artful if not calculating touch to the A-Rod mess. “There is much more mileage to be gotten out of Rodriguez after all this blows over, and Nike wants to be in a position to take advantage when the rehabilitation begins,” Reeder said.

Nike used the same blueprint to perfection six years ago when Kobe Bryant faced rape allegations in Colorado. The company shelved its active promotion of the NBA all-star until he was commercially viable again after the charges were dismissed.

Not that bad press is always a bad thing. Some brands purposely pick spokespeople with slightly tainted résumés to attract consumers who like a little rebellion. Entertainer Sean "Diddy" Combs, twice accused of assault and once indicted on weapons charges (later cleared), has endorsed products for Burger King and Ciroc Vodka.

“Companies do extensive research on image sales and some foster bad-boy or bad-girl campaigns. Those campaigns sell product,” said Mina Sirkin, a Los Angeles attorney who served as a frequent TV legal expert on the death of Anna Nicole Smith and the conservatorship of Britney Spears.

“The wholesome image is not selling as well these days,” Sirkin said. “The talent know this and know that bad acts sell products and, therefore, get better sponsorships, so there is an open invitation to bad acts.”

The bigger question, said Sirkin, is this: Which nasty deeds are real and which are manufactured by a celebrity’s publicity team and then “leaked” to the media?

Consider IndyCar driver Danica Patrick — feisty, even a fighter, on the track and not afraid to don skimpy swimwear to boost her racy persona. Patrick’s sponsors include GoDaddy.com and Motorola. But is she really all that edgy? Thousands of fans and consumers are buying it.

“There’s a sense of something waiting to happen, a bit crafty,” said Bonnie Russell, a Patrick fan and founder of an attorney-locator service in Del Mar, Calif. “I just totally see Danica profiting after being bad. I really do think Danica could get away with a lot.”

Some celebs earn second chances

The same holds true for law-breaching celebrities who have otherwise shined with virtue like Phelps, who also weathered a 2004 DUI case. The 14 gold medals he has earned for Team USA have bought him a pool-full of public tolerance, as well as second and third chances as a celebrity endorser, branding experts said.

“Goodwill is what drove the general public’s response to his mistake,” said Courtney Leddy, vice president of Ketchum Sports Network, which helps clients like Kodak and FedEx with sports sponsorships. “People didn’t agree with his choice, but they balanced that with their positive feelings.”

Of course, there are some limits to the lapses — and to what sponsors and companies will agree to swallow.

Some crimes or social blunders will bring a swift, permanent end to a celeb’s endorsement career. It is generally accepted in the industry that racist remarks, certain religious commentary and violent crime convictions, including domestic violence, will earn a sponsorship death penalty. Even public apologies don’t help. Which is why most branding experts don’t see singer Chris Brown emerging commercially from his alleged assault on girlfriend and fellow entertainer Rihanna. Wrigley’s gum dropped Brown after the incident.

Animal cruelty, like the case that brought down ex-NFL quarterback Michael Vick, may be another unforgivable offense among sponsors and shoppers. Some branding experts see no resurrection of Vick as a pitchman.

Again, though, the ethical line is blurry, even on this point.

“The memory tends to fade as the crisis fades,” said Melissa St. James, assistant professor of marketing at California State University Dominguez Hills. She wrote her doctoral dissertation on celebrity endorsements and has published several research papers on the impact negative publicity can have on celebrity spokespeople.

“What Michael Vick did was horrible,” St. James said, “but I think even that will fade with time.”