Some of the world's leading paleontologists are attempting to re-create a dinosaur — or something a lot like a dinosaur — by starting with a chicken embryo and working backward to engineer a "chickenosaurus" or "dinochicken," project leader Jack Horner told Discovery News.

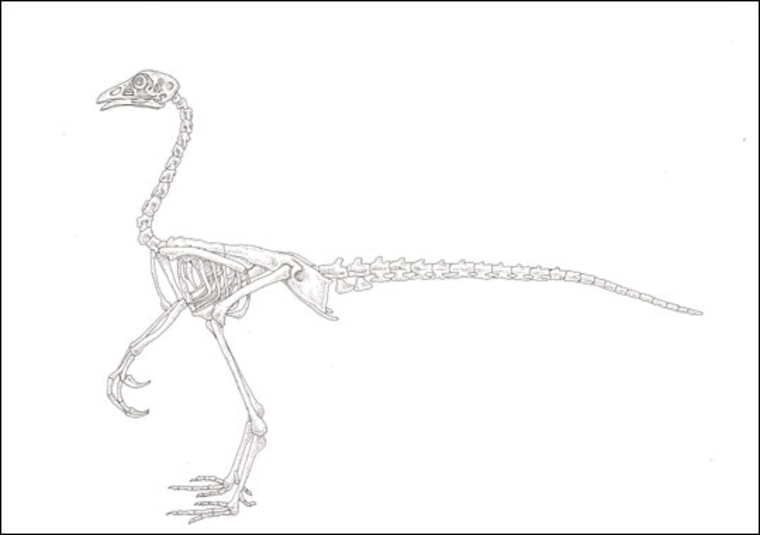

Such "reverse evolution" has been successfully performed in mice and flies, but those studies focused on re-introducing just a few bygone traits. The dinochicken project instead has the goal of bringing back multiple dinosaur characteristics, such as a tail, teeth and forearms, by changing the levels of regulatory proteins that have evolved to suppress these characteristics in birds.

"Birds are dinosaurs, so technically we're making a dinosaur out of a dinosaur," said Horner, a professor of paleontology at Montana State University and curator of paleontology at the Museum of the Rockies.

"The only reason we're using chickens, instead of some other bird, is that the chicken genome has been mapped, and chickens have already been exhaustively studied," added Horner.

He and colleague James Gorman, deputy science editor of The New York Times, have just co-authored a new book, "How to Build a Dinosaur: Extinction Doesn't Have to Be Forever," which describes the project in detail.

Although the plan seems more like a page out of the fictional "Jurassic Park," Horner assured it is real and is already underway.

"A number of people in a number of different places are moving forward with the project slowly and carefully," he said.

One such researcher is Hans Laarson of McGill University in Montreal. Laarson and his team are analyzing the genes involved in tail development and researching ways of manipulating chicken embryos in order to "awaken the dinosaur within."

By bringing back a tail to a chicken, Laarson and his colleagues will promote growth of the spinal cord. In the future, Horner believes this work could lead to medical advancements that will benefit humans.

"The growth of the tail is tied to the growth of the spinal cord, and spinal cord birth defects in humans are a major medical problem," he explained. "Learning more about what prompts and stops tail growth could give us important insights about serious human birth defects."

Other medical breakthroughs could also occur, he said, since "genomes made of genes made of switches" function similarly in all animals, including humans.

There is no danger of the proposed dinochicken escaping and populating the world with dinosaurs, Horner said, since only the chicken's development, and not its genome, would have been affected. If the creature did somehow escape and could mate, the result would just be a regular chicken.

If a chicken embryo does not grow properly in the lab, or if it could not "survive comfortably," Horner said, "we would never let it hatch."

Kevin Padian, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California at Berkeley and a curator at the UC Museum of Paleontology, told Discovery News he supports the project.

"The important thing that Jack and Jim are saying here is that there is a lot of information stored in our genes that we don't use — genes that determine features that evolution has suppressed, for various reasons," Padian said.

"We now have the tools to 'reverse-engineer' some of those constraints and produce traits that look a bit more like those ancient features," he added. "This tells us how genetics, development and evolution are related, so it's tremendously important."

When and if the dinochicken is created, Horner looks forward to bringing it out on a leash during lectures.

"We're always looking for novel ways to get the general public interested in science," he said, "and you have to admit, it would be better than a slide show for demonstrating evolution."