Even 20 years later, the shooting, chaos and death of the final assault on Tiananmen Square remain vivid in the mind of former soldier Zhang Shijun. Today, he has become one of the few to publicly voice regret.

In bearing witness about his role in the military crackdown on the 1989 student demonstrations in Beijing, Zhang says he hopes to add momentum to calls for an investigation and reassessment of the protest movement — and to further its ultimate goal of a democratic China.

"I feel like my spirit is stuck there on the night of June 3," Zhang, 40, said in an interview at his home in the dusty northern city of Tengzhou, referring to the date in 1989 on which the final assault began.

Zhang's tortured memories have gained a global audience among the Chinese dissident community in the weeks since he posted an open letter to president and Communist Party leader Hu Jintao online. In it, he relates some of what he saw when posted on the night of June 3-4, along with an account of the persecution he underwent after asking for an early discharge, and his belief that China must eventually clear its collective conscience of the tragic events.

"The responsibility can't just be laid on the military," Zhang said. "It's really the responsibility of all Chinese."

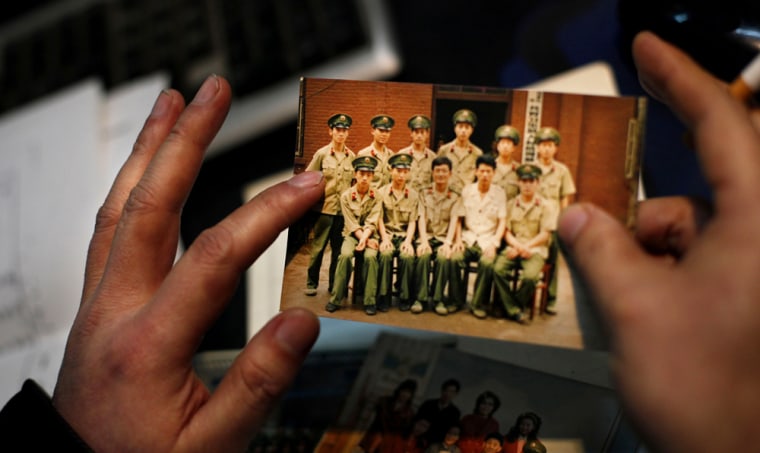

Zhang was just 18 when he joined the elite 54th Group Army's 162nd Motorized Infantry Division based in the central city of Anyang. Less than three years later, with student-led protests gathering pace, Zhang's units were ordered to Beijing on April 20, 1989. There, they camped on the capital's southwestern edge while citizens erected barricades to block their progress toward Tiananmen, the vast square in the heart of the city where the students had established their headquarters.

On June 3, their orders came: Drive through to the square and get it cleared.

Bricks and rocks

Heading east toward the square, Zhang and his comrades abandoned their vehicles as bricks and rocks flew at their heads and bullets were fired at them by unknown shooters from upper stories of apartment buildings. Members of his unit fired over the heads of civilians as a warning, said Zhang, who added that he himself was serving as a medic and unarmed in the final assault.

Zhang said he knew of no deaths caused by the troops of the 54th army — a claim impossible to disprove as long as official files on the events remain closed. Most of the post-crackdown reports pinned the hundreds, possibly thousands of deaths among civilians and students on two other units, the 27th and 38th group armies based outside Beijing.

By daylight the next morning, Zhang said his unit established a cordon along the square's southern edge between a KFC restaurant and the mausoleum of communist China's founder, Mao Zedong.

Zhang said other details were still too sensitive to tell, suggesting atrocities such as the shooting in the back of unarmed students and civilians. While other eyewitnesses have made similar allegations, they remain impossible to independently confirm.

Smoking and surfing

After the soldiers' withdrawal, Zhang said he asked for and eventually obtained an early discharge, never having expected to be sent to fight ordinary citizens. After returning to Tengzhou he began a discussion group promoting market economics and politics, but was arrested on March 14, 1992, and sentenced to three years in a labor camp for political crimes. Then, as now, he regarded the charges as trumped-up retribution for his leaving his unit early.

After his release, Zhang said he traveled to find work, returning to Tengzhou in 2004 to deal in arts and antiques and help raise his 13-year-old daughter. In a dingy study adorned with his calligraphy and curio collection, he spends hours at the keyboard of his battered computer keeping in touch with other dissidents and surfing the Internet politics discussion boards.

Zhang, who retains the close-clipped haircut and restrained demeanor of a military man, said he came forward partly to seek redress for his jail camp term, but that revisiting the Tiananmen events remained his main focus.

"Back then, we felt that it would all be addressed in the near future. But ... democracy just seems further and further away," Zhang said between puffs on an endless string of "General" brand Chinese cigarettes.

Zhang said he hoped his example would inspire more ex-soldiers to come forward and form a network, but appeared reluctant to cast himself as an organizer, perhaps wary of the party's tendency to single out perceived opposition ringleaders for harsher punishment.

Already, his activities have aroused official attention. Visitors have been followed by police and Zhang said authorities who summoned him Wednesday, a day after the AP interviewed him, ordered him to shun the foreign media.

Retired professor Ding Zilin, an advocate for Tiananmen victims whose teenage son was killed in the crackdown, said Zhang is one of only a few soldiers to speak up about the 1989 events. Many who took part in the crackdown continue to hide their involvement, refusing to wear the commemorative watch issued to all martial law troops, she said.

"Twenty years have passed, but if the soldiers still had conscience, there may be others who stand up," Ding said.

Nicholas Bequelin, Asia researcher for New York-based Human Rights Watch, said testimony from those who took part in the crackdown was invaluable to forming a full view of the events.

That Zhang was willing to come forward, Bequelin said, simply reinforced the conviction among many that "in the long run, a reassessment of those events is inevitable."