The race is on to develop smaller, more powerful and more solid batteries for devices like laptop computers, cell phones, GPS receivers and other portable devices.

Scientists at MIT are taking the opposite approach, developing large, eco-friendly stationary batteries made entirely from liquid metal that would store large amounts of power from wind farms or solar cells or serve as backup power sources for hospitals.

"Since these batteries won't be in someone's hand or in a car, we don't have to make them crash-worthy, idiot-proof, and it doesn't have to operate at around body temperature," said Don Sadoway, a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who, along with graduate student David Bradwell and fellow professor Gerbrand Ceder, is developing the molten metal battery.

"Our batteries have no solid materials in them; no solid electrodes, no solid membranes, no solid anything," said Sadoway.

Any battery, solid, liquid, or a combination of the two, is simply a way to store energy chemically. To do this, any battery needs three parts: a positively charged cathode, a negatively charged anode, and a membrane between the positive and negative charges.

Most batteries, including the one in your laptop or TV remote, use solid materials like zinc or lithium cobalt for the cathode, graphite for the anode, and a liquid salt solution for the electrolytic membrane.

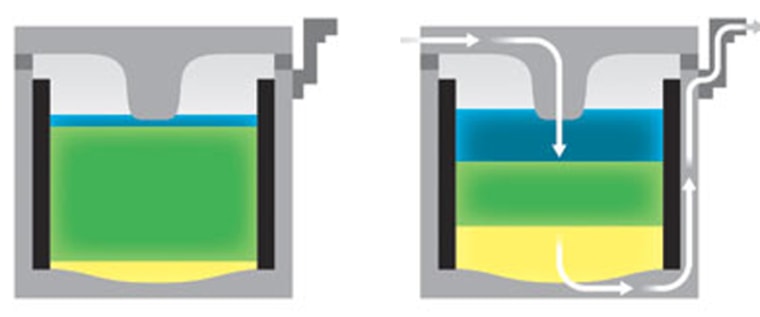

Sadoway's battery is different. The anode, the cathode, the membrane, all of them are liquids, hot, molten, and sloshy liquids.

Sadoway has tried many different combination of liquid materials during the last few years. One of the first compilations used molten antimony and magnesium as the charge holders with a layer of sodium sulfide between the two.

The three layers don't mix with each other because each material has a different weight. They naturally separate into three layers. If something disturbs those layers they will naturally separate again because of their weight.

Sadoway won't release specific details of his current battery materials. Whatever they are made up of, the batteries are encased in stainless steel and are about the size of a soda can.

Like the materials inside the battery, the final size of the battery is yet to be determined.

"This should be easy to scale up. If we want to make a battery the size of a 33 gallon garbage can we can do it," said Sadoway. "If we want to make [a battery] the size of a football field we could do it."

One issue in scaling the size of the battery up is coming up with a cheap way to keep the liquid metal liquid. Right now the batteries have to be heated to a minimum of 500 degrees Celsius, just above the maximum temperature of the standard home oven.

Liquid metal batteries would require about the same safety measures as a home oven, and could one day become a part of homes, hospitals, and other permanent structures. The batteries would be ideal for storing energy from wind or solar farms for use when the sun isn't shining or the wind isn't blowing.

Fully liquid metal batteries are most likely to replace other molten metal batteries (which have a solid membrane between anode and cathode), such as sodium sulfur batteries, which serve as back up batteries for hospitals during power outages, or could draw power from the electrical grid at night and then put the energy back into the grid when it's needed most, during the day.

Fully liquid metal batteries are still years away however, say both Sadoway and other battery experts, including Marca Doeff, a material scientist and battery expert at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California.

"This is still a conceptual idea," said Doeff. "There are still engineering challenges that need to be overcome."