Baby chickens aren't just cute — they are also whizzes at math, according to a new study.

The study, published in the latest Proceedings of the Royal Society B, presents the first known evidence that any non-human animal can perform consecutive addition and subtraction calculations on the same set.

It is also "the very first demonstration of some arithmetic ability in young animals," lead author Rosa Rugani told Discovery News.

Since the chicks could work with numbers up to five, and prior research suggests the limit for human newborns is three, it's possible that chicks could beat babies if the two groups were pitted against each other in a math contest.

Taken as a whole, however, the study supports the theory "that animals and humans share a non-verbal, and even pre-verbal in the case of humans, numerical system" that can perform precise arithmetic on small number sets — "with a limit of three or four" -- and make estimates about larger sets, said Rugani, a researcher in the Center for Mind/Brain Sciences at the University of Trento in Italy.

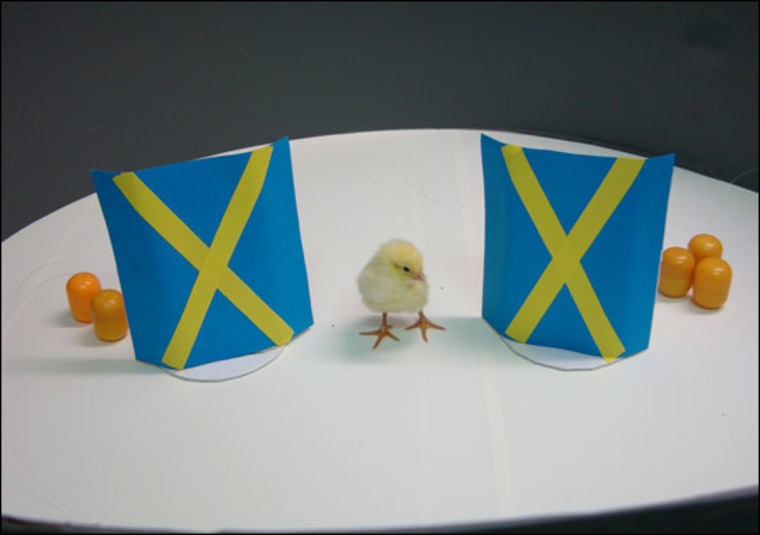

Rugani and her colleagues tested the arithmetic skills of 17 domestic "Hybro" chicks derived from the White Leghorn breed. To get them accustomed to the experiment objects, the scientists reared the chicks with five yellow toy balls, which the baby chickens accepted as members of their own family.

The chicks "become socially attached to the imprinting object, even though this is an artificial one, and respond by promptly following the ball if it is moved, and by emitting distress calls if the ball is removed, or soft calls when the ball is placed back in their home cage," Rugani explained.

The scientists next set up a room like a darkened theater, with two opaque screens at the front. As the chicks sat in front of the screens, the scientists dangled the balls, tied to fine threads, behind the screens.

The goal of each experiment was to have the chicks choose the largest set. Animals generally gravitate toward larger groups of individuals or things, likely due to a youngster's reliance on others.

The most complex test required the chicks to keep track of the number of balls through addition or subtraction, since balls were transferred either individually or in sets from one screen to another.

Despite the ball disappearing acts, the chicks spontaneously chose the screen hiding the larger number of hidden toys. The birds made their selection by sticking their heads behind the correct screen to see their old "companions."

As for the chicks' ability to work with a larger set than human babies could, the researchers speculate it might have something to do with family size. They suspect chicks might even be able to work with up to 10 balls, because broods often consist of eight to 10 siblings, but Rugani said she and her team haven't yet "investigated the upper limit of chicks' ability in this task."

Since non-human animals appear to have natural math skills, it's now thought that children, whose math abilities far exceed those of chickens as the two species mature, don't need to master the logic of arithmetic tables to add and subtract.

A preliminary study conducted by Harvard researcher Elizabeth Spelke and colleagues showed that five-year-old children could even handle simple word problems like, "Sarah has 64 candies and gives 13 of them away, and John has 34 candies. Who has more?"

"We've known for some time that adults, children and even infants and nonhuman animals have a sense of number," Spelke said. "We were surprised to see, however, that children spontaneously use their number sense when they're presented with problems in symbolic arithmetic."