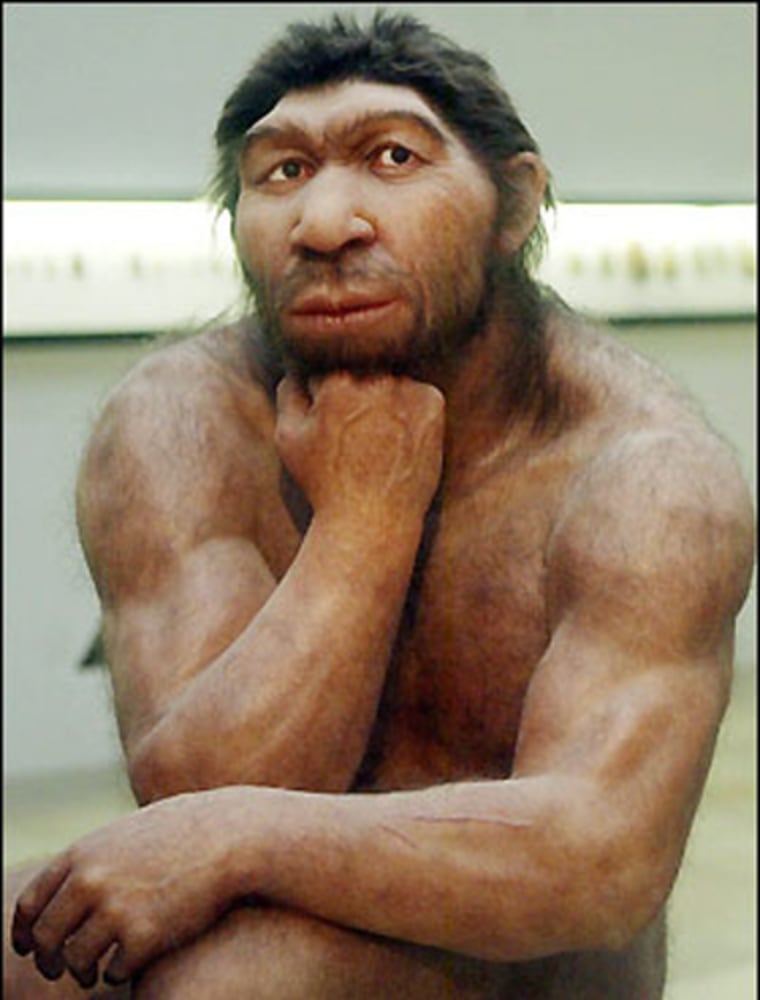

We tend to think of Neanderthals as one species of cavemen-like creatures, but now scientists say there were actually at least three different subgroups of Neanderthals.

Using computer simulations to analyze DNA sequence fragments from 12 Neanderthal fossils, researchers found that the species can be separated into three, or maybe four, distinct genetic groups.

The evidence points to a subgroup of Neanderthals in Western Europe, another in Southern Europe near the Mediterranean, a third in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and possibly a fourth in Western Asia. These groups have been postulated before, but this is the first study analyzing DNA data to look for genetic variations differentiating the subgroups.

Neanderthals are a hominid species that lived between about 130,000 and 30,000 years ago. They co-existed with humans for a while, and may even have interbred with us.

"Because the Neanderthals lived in a very vast territory, and their evolution took place over a very long time, we wonder if there were subpopulations or if it was a unique population," said researcher Silvana Condemi, a paleoanthropologist at the Universite de la Mediterranee-CNRS-EFS in France. "Other studies show differences between Neanderthals and modern humans. For the first time we are working just within Neanderthals and taking into account the diversity within that group."

Condemi and Virginie Fabre and Anna Degioanni, also of the Universite de la Mediterranee, describe their findings in Wednesday's issue of the online journal PLoS ONE.

The researchers tested various hypotheses, including the idea that all Neanderthals belonged to a single homogeneous population, or that Neanderthals could be divided into two, three or more subgroups. They found that the three- and four-group model best fit the data by accounting for the genetic discrepancies seen in the samples.

The authors admit that their categorization is based on limited data, since they only have fragments of mitochondrial DNA sequences from a small sample of individuals.

Princeton University paleoanthropologist Alan Mann agreed, and said it's too early to draw bounds around subpopulations because scientists don't have any data from individuals outside the bounds, such as from Neanderthals in Africa or Southeast Asia.

"My view is this is very interesting research, but it's very premature in our study to be able to draw any but the most generalized and preliminary conclusions," he said in a phone interview. "I like the data they present. But at the moment we have to be extremely careful about exactly what we make of this."

In the future, the researchers would like to compare their genetic data with what is known about physical distinctions among Neanderthals from different regions, as well as cultural differences, such as unique tool use among various populations.

"What is nice is that there are some variations in the genetics, and we see also from the bones and teeth that there is some variation," Condemi told LiveScience. "We give a confirmation that the Neanderthals are not one homogeneous group."

It is not known for sure what eventually caused Neanderthals to die out, while we Homo sapiens have survived to this day. Likely reasons for their demise are competition with humans and climate change.