In 1969, an aeronautical engineer at North American Rockwell discovered a discrepancy in his paycheck: Every hour, he was being overpaid by roughly 2 cents, or one-third of 1 percent of his pay.

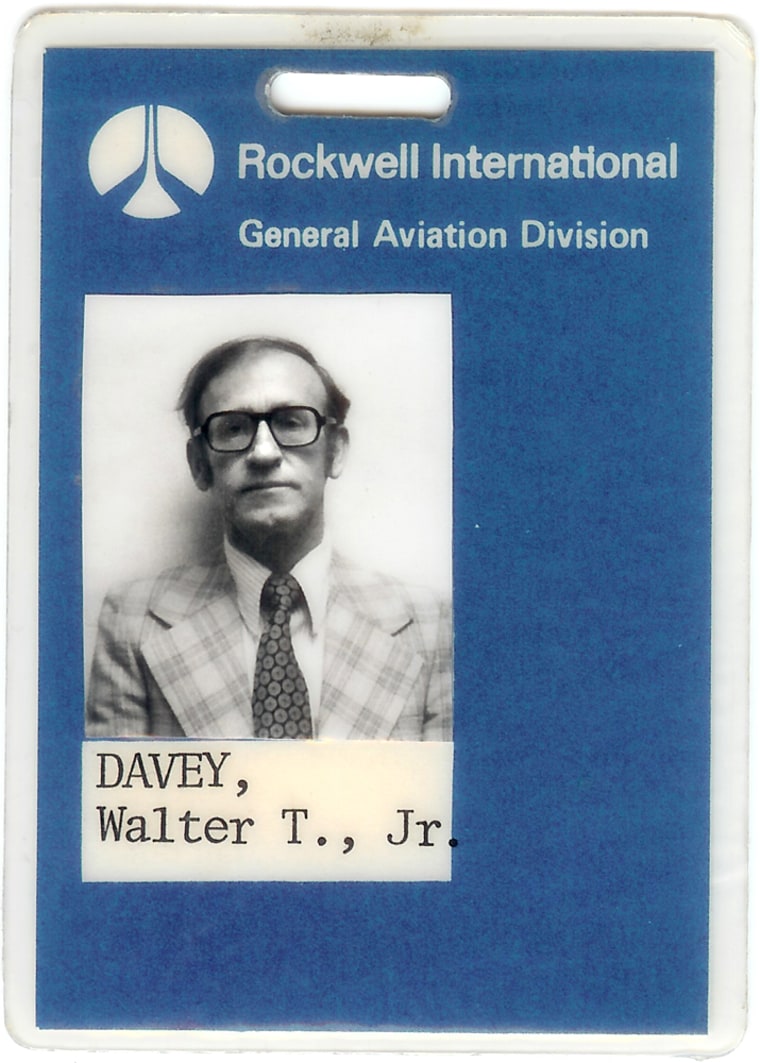

Spurred by an incentive program that rewarded employees for finding wasteful spending, Walter T. Davey submitted the discovery to his superiors and suggested a simple fix.

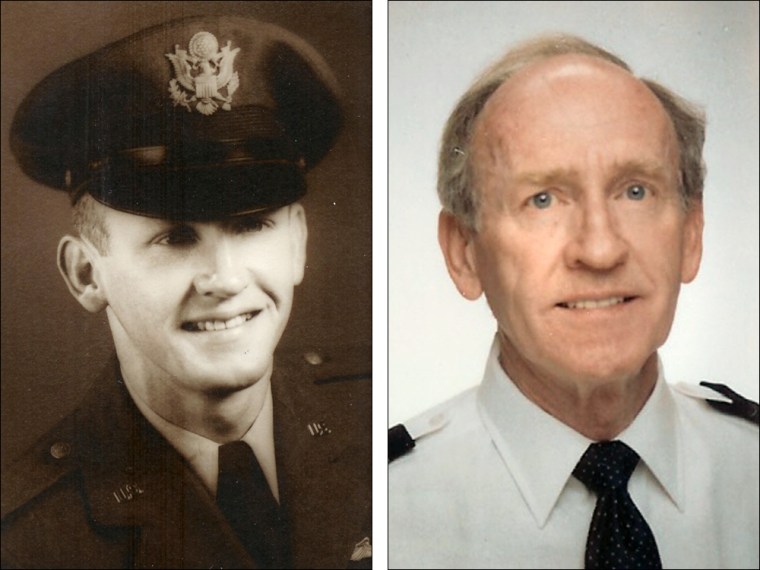

“It was so simple to correct,” said Davey, a 79-year-old retired Air Force colonel now living in Newport Coast, Calif., “just change a few digits in the coding software.”

A surreal experience followed: For decades, Davey has attempted to correct a calculation that he believes has cost taxpayers several billion dollars. He has alerted contractors, legislators, and federal auditors -- all to no avail, even though a 1981 federal report seemed to confirm his calculations. Through it all, he said, no one has challenged the numbers.

“I’ve been frustrated since I was denied that suggestion back in ’69,” Davey said. “Doggone it, I’m going to put it in my will that someone keep pursuing this.”

As President Barack Obama seeks to crack down on costs overruns in the defense industry, Davey’s experience provides a telling illustration of the challenges facing reformers.

Legislators ignored Davey’s letters. Federal auditors deferred to Congress. Lobbyists “descended on it and tore it into a piece of Swiss cheese,” in the words of a former executive member of the Cost Accounting Standards Board, which is charged with reviewing accounting standards for high-dollar federal contracts.

New era for contractors?

But now, reform advocates say, the tenor has changed in Washington as the Obama administration has, on several occasions, signaled its intent to fundamentally overhaul the relationship between the Pentagon and defense contractors. Last month, Obama declared an end to the “days of giving defense contractors a blank check.”

“There’s optimism that this administration wants to reverse some of the pro-contractor trends of the past 15 years,” said Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight, a nonprofit that investigates allegations of federal misconduct. “Contracting has become a front-burner issue.”

That has renewed hope for citizen activists like Davey, who said he has encountered endless obstacles and congressional dead-ends.

“Until recently I don’t even think you could bring an issue like this up,” said Richard C. Loeb, an adjunct professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law who reviewed Davey’s documents. “The fact you couldn’t have that debate until recently is really the bigger problem. At least now you can have a discussion about it without being thrown out of the room.”

But Loeb and other critics say legislators aren’t eager to challenge the powerful defense lobby about a figure that’s a relative pittance in the overall defense budget – even if it exceeds $100 million annually.

“(Davey) has always had a good point,” Loeb said. “It would be extremely easy to fix. It could save taxpayers upwards of tens and tens of millions of dollars a year.”

Spokesmen for several congressional representatives contacted for this story declined to comment, saying the issue had only recently come to their attention. The office of Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., which has been in communication with Davey in recent weeks, said it is “looking into this issue.”

An Open Secret

What Davey stumbled across in 1969 is an open secret.

Davey, a father of 10 children, said he and his wife always scrambled to find extra income for their growing family. At the time, Rockwell offered a reward to workers who discovered ways to save money. Davey submitted his idea.

“I have to be frank,” Davey said. “I was hoping to get some small financial award out of it. Then, as it grew over the years, I thought, ‘Wow, this is bigger than me.’”

How big remains a matter of debate: The Project on Government Oversight, which reviewed Davey’s findings last year, estimated the change could save taxpayers $270 million a year. Multiply by 40 years – the length of time since Davey made his discovery -- and the figure grows to an astounding $10.8 billion. (That figure, however, doesn’t account for inflation or yearly shifts in spending.)

The federal government has acknowledged problems with the conversion rate, which once applied to federal employees but can still be used by defense contractors.

In 1981, a study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that this tiny conversion factor cost taxpayers $120 million a year in faulty payments to federal employees alone – not including employees like Davey at private contractors. Four years later, as the Reagan Administration attempted to rein in federal spending, Congress passed the Budget Reconciliation Act, which changed the calculation for federal employees.

But it exempted defense contractors for reasons that remain unclear.

“Had Congress thought it necessary, they could have expanded its coverage to contractor employees as well,” the GAO’s director of acquisition and sourcing management wrote to Davey in 2008. “For whatever reason, Congress chose not to.”

40 years later, the discrepancy remains

Today, the discrepancy remains. Federal employees are paid based on 2,087 hours in a work year, which accounts for the leap-year cycle. Though a full audit has apparently never been completed, “most” defense contractors are paid on a 2,080-hour workweek, according to the GAO.

What does that mean?

Take an engineer at a defense company who earns $104,000 each year. When that engineer is assigned to a federal contract, he or she is paid at an hourly rate, according to the Project on Government Oversight, which estimated the costs.

Divide $104,000 by 2,080 to get the hourly rate that the defense company can charge the government: $50.

However, use 2,087 hours a year – the rate for federal employees - and the contractor can only charge the government $49.83. In other words, the defense engineer at this pay level earns an additional 17 cents for every hour, the group found.

That sounds minuscule. But contract employees account for more than half of the federal workforce, an estimated 7.6 million jobs in 2005, according to Dr. Paul C. Light, a professor at New York University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute.

“How much of a savings will it be? It’s millions,” Loeb said. “Reasonable people can’t disagree on this. It’s standard arithmetic.”

As contracts grew, oversight fell

The discovery by Davey is a small part of a much bigger problem: The massive cost overruns in federal contracts.

Since 2000, federal contracting has more than doubled to $532 billion last year. Federal cost-plus contracts – like those targeted by Davey – grew 75 percent under the Bush administration, and development costs for the Defense Department’s major weapons programs exceeded their original budgets by $300 billion in 2008, the Government Accountability Office said in a report last month.

Critics say the problem stems from the cost-plus contracts, which allow the defense industry to preserve profits even if projects go over budget or if the Defense Department underestimates the initial budget.

The contracts have long been used to encourage research and development -- including big-ticket projects such as the Trident II Missile and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. Otherwise, supporters say, such projects might otherwise be too risky in the initial research stages for contractors to undertake.

“They are essential, particularly when you are dealing with the research and development,” said Cord Sterling, vice-president at Aerospace Industries Association, which represents major defense and aerospace businesses. “If you are really reaching to develop a new technology and new capabilities, you are going to see an increase in that type of activity.”

But those contracts are increasingly being used for less-risky service contracts, according to Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based foreign policy think tank.

And even as those contracts ballooned, the number of federal employees overseeing them grew only slightly and the federal Cost Accounting Standards Board shrunk to a single staffer, making it necessary to abandon active investigations, according to Loeb, the board’s former executive secretary and counsel.

“The contractors hated the CAS Board and got the Bush people to basically shut it down,” Loeb said by e-mail.

A ‘time-consuming and fruitless effort’

That has only made Walter Davey more resolute. Three years ago, he and his son, Jim, a commercial airline pilot, signed and mailed letters to each of the 535 members of Congress.

They received three form letters in response.

“It was an expensive, time-consuming and fruitless effort,” Davey said. “There’s a long list of people we’ve been rebuffed by. But I don’t want to just give up.”

Amey, the Project on Government Oversight’s legal counsel, applauded Davey’s efforts but sought to dampen optimism that change is coming despite the Obama administration’s pledges to rein in defense overruns.

“A lot of people have taken advantage of the system to reap as much in taxpayer dollars as possible,” Amey said. “But when you’re going up against the contractor lobby – whether you’re an individual across the country or a public interest group or a government employee – it’s a tough road.”